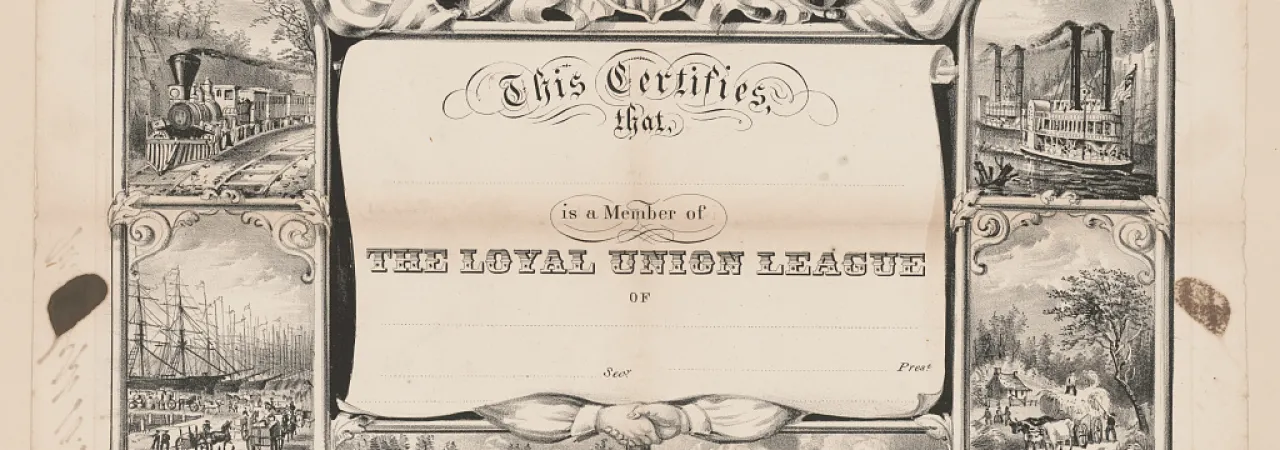

1863 Loyal Union League Certificate

During the American Civil War, the many organizations adopted variations of the term “Loyal League.” Hallmarks of groups forming under this designation included a strong support for the Union cause—reuniting the country and upholding an interpretation of the United States Constitution that implied a perpetual union of the states. Women’s charitable groups and men’s political clubs took the name Loyal League or variations of it. Politically, some loyal leagues declared they would try to set aside party platforms or smaller causes to focus on ending the war and reuniting the country.

Within free Black communities, the Loyal League followed a historic pattern of organizing for political safety and advocacy. Since the early decades of the 19th Century, free African Americans had held conventions to debate the meaning of the United States Constitution, study political party platforms and find new advocacy opportunities for the Black community. These groups and the conventions they held went by different names.

For example, in 1831, Baltimore residents led by Hezekiah Grice, William J. Watkins, Sr. and James Deaver formed the Legal Rights Association. This group explored what rights free African Americans should have under the laws and the U.S. Constitution and cataloged when and how those rights were denied. In 1855, another group with the same name organized in New York City to challenge racial segregation in the public streetcars. These two Legal Rights Association groups were forerunners to later organizations like the National Equal Rights League and the NAACP.

The free African Americans also organized conventions, philanthropic groups, and other leagues throughout the Antebellum era, advocating for abolition, pressing for civil rights or considering futures in other countries as United States law became more restrictive to them. These organizations became powerful networks to inform, protect and rally Black communities—especially during the Civil War on the homefront or as spies and soldiers.

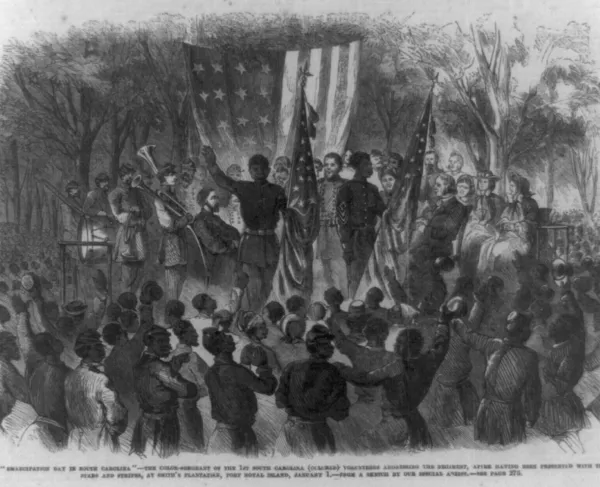

Both white and Black communities organized Union Leagues (sometimes called Loyal Leagues) during the Civil War. Officially organized groups operated as patriotic clubs, supporting the Lincoln administration and were usually secret and oath-bound. The political influence of these Loyal Leagues extended into the south as advancing Union armies carried the ideals and practical support for the war effort into Federal-occupied territory.

Due to limited documentation in the historical record and the secretive nature of the Loyal League networks, it is difficult to pinpoint the extent of the influence these groups had on the war effort. Some accounts suggest that Loyal Leagues (or similar equivalents) in Black communities sent spies into the Confederacy and regularly gathered valuable military intelligence for the Federal armies. Certainly, African American—both enslaved and free—brought notable information to Union troops which altered the course of campaigns or naval actions. The extent of an underground Loyal League in these operations or if there were alternative goals is more challenging to track through surviving primary sources. The late historian Hari Jones theorized with some documentation that League spies may have even delivered misinformation to Union officers in 1862, hoping to prolong the war until abolition became an official war aim.

Immediately following the end of the Civil War in 1865 and as the Reconstruction Era began, the term Loyal League took a new meaning. In David A. Payne’s History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, he explained: “Shortly after the close of the Civil War an organization was formed among the freedmen known as the Loyal League, an organization that was initiated by Northern white men, many of whom were ex-federal officers. The objects of the League were fraternal and cooperative. It aspired to bring all the loyal elements in the South into harmonious relationship, with a view of making secure the fruits of the Civil War. The only symbol of secrecy was a grip. The usual meeting place was a church or a school house. The only oath administered was that of loyalty and obedience to the government of the United States. There was not even the dream of making reprisals on the Confederates....” The Loyal League chapters became the targets of the newly formed Klu Klux Klan, especially as the League organized and tried to protect the new civil and enfranchisement rights enacted by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

The Antebellum Era, the Civil War years, and the Reconstruction Period saw legal associations and loyal leagues grow in influence throughout free Black communities. Through these organizations, African Americans sought to shape, expand and protect their rights through state and national law. The Loyal League gave opportunity for African Americans to taken visbile and invisible roles in the Union war effort, using the power of connections and network to gather military intelligence or influence politics. The extent and full outcomes of these Loyal Leagues may still be shadowy and difficult to trace in the pages of history, but the legacy of advocacy and action to safeguard and build a better nation continues.

Further Reading

Phyllis Field, “Union League,” Organizing Black America: An Encyclopedia of African American Associations (New York: Garland Publishing, 2001)

Michael Fitzgerald, The Union League Movement in the Deep South: Politics and Agricultural Change During Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989).

Daniel Alexander Payne, History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Volume 2 (1922).

Proceedings of the Convention of Loyal Leagues held at Mechanics' Hall, Utica, Tuesday, 26 May, 1863. (Accessed through Google Books, November 2025).