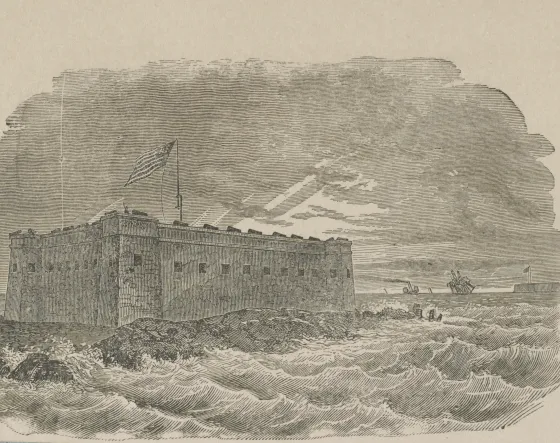

"Fort Taylor, Key West, Fla." 1861.

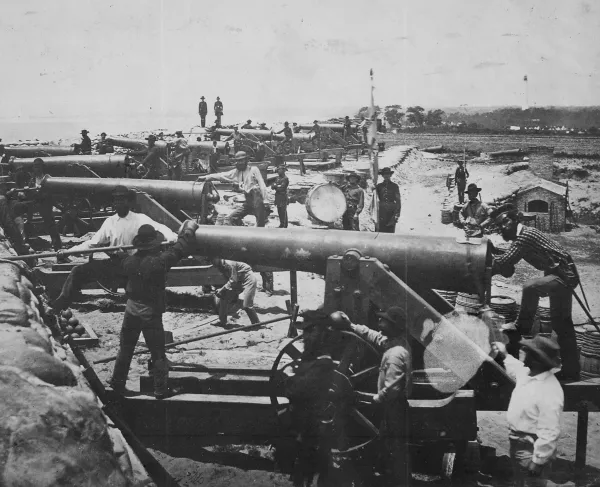

Fort Taylor, on the southwest tip of Key West, overlooks the confluence of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. Cruise ships pass, and fade into the background as beachgoers soak up sun, swim, snorkel, and witness magnificent sunsets. Today, Fort Zachary Taylor Historic State Park is one of the most sought after attractions in Key West and in the Florida Park System. During the Civil War, Fort Taylor was the “Gibraltar” of the Gulf, defending U.S. interests against European powers in the Western Hemisphere, and headquartering the East Gulf Blockading Squadron. Union seamen brought 299 captured blockade runners, their crews, and tons of supplies to Key West, which contributed to the Union victory as supplies in the Confederacy became scarce. U.S. authorities auctioned off captured vessels and cargo and held blockade runners and disloyal civilians – from Key West and elsewhere – in Fort Taylor.

Before the war, Americans North and South recognized Key West’s significance. In 1856, the Key West Key of the Gulf contended that Forts Taylor and Jefferson (Tortugas) would, in any maritime struggle, “constitute the most important rallying points for all the commerce of the Gulf of Mexico” since the waters between the Florida Keys, Cuba, and the Bahamas would be an attractive theater for naval warfare. Fort Taylor guarded these waters and oversaw the “entire cotton crop of the country” on its way to market. The Lewisburg (PA) Chronicle’s Key West correspondent agreed. In June 1860, he contended that, “In the case of a war with any maritime nation, the possession of Key West will be invaluable to us, both as a safe retreat for our merchantmen, and as a convenient harbor for men-of-war to recruit or get coal, water, and sea stores.” The Jackson, Mississippi Weekly Mississippian echoed these sentiments in January 1861, arguing that Fort Taylor could not be “too highly estimated,” and urged that it “be taken possession of without delay by the Southern troops.”

This exhortation came too late, however. John Brannan, Captain of the 1st U.S. Artillery, and Captain Edward Hunt, Chief of Engineers, secured Fort Taylor shortly after news of Florida’s secession (January 10) reached Key West on January 12. Brannan, the ranking officer, moved his troops under cover of night from the U.S. Army Barracks across the island to Fort Taylor. His move elicited praise in the North. On January 14, the New York Times proclaimed that “The United States should never let this work go to Florida,” since “it concerns the commerce of the United States, and is no local fortress.” Times editor, Henry Raymond, in a speech to the Republican Club on February 26, 1861, argued that the U.S. should keep all its coastal forts, “especially those which control the great channels of commerce,” like Fort Taylor. He did not want to see Fort Sumter taken but considered it to be “of no practical importance” compared to Fort Taylor.

To maintain control, Brannan and Hunt knew that they needed to subdue Key West’s secessionists. The pro-secession Key of the Gulf denounced Hunt’s proclamation that he would turn Fort Taylor’s guns on the town if they did not “behave themselves to his liking.” U.S. authorities declared martial law at Key West on May 10, 1861.

Major William French, commanding officer at Key West, took actions to discourage Secessionists. He forbade anyone commissioned under the authority of the state of Florida to levy taxes, assessments, or levies, and ordered all seditious and disaffected persons removed from the island. A correspondent aboard the U.S. Steamer Crusader, anchored at Key West, praised French’s initiatives. He stated that although almost half of the island’s residents, many of whom were wealthy and influential, were “bitter Secessionists,” they were now “more humble” and U.S. authorities could “easily manage them.”

French’s other dictates deeply embittered Secessionists: He ordered Confederate flags down from shops and houses, disbanded the “Island Guards” – a pro-Confederate militia group, banned liquor sales, ordered all adult men who remained at Key West to take the U.S. oath of allegiance, and organized 200 men into two Union volunteer companies. Confederate sympathizer Robert Watson concluded on September 27, 1861, that Key West was “rather unsafe for a southern man” and, disgusted, left. Residents who remained had to adjust to military occupation, and a variety of U.S. enemies, both from the island and beyond, experienced imprisonment at Fort Taylor.

U.S. authorities often used Fort Taylor to punish blockade runners and individuals suspected, or who committed actual acts, of disloyalty and challenged martial law. In July 1861, a correspondent of the Unionist Lewisburg (PA) Chronicle, wrote that Major French instituted a “mild reign,” but one local Methodist minister advocated that burning pine knots be inserted into the flesh of Unionists to “convert them from their heresy.” U.S. authorities imprisoned him in Fort Taylor for “inciting rebellion from the pulpit.”

Fort Taylor also held prisoners awaiting either transfer to other locations or court martial. On November 29, 1861, the National Republican (D.C.) reported that the U.S. steamship Connecticut captured the British schooner Adelaide of Nassau, which was loaded with coffee, lead, swords, and the “supercargo, Lieutenant Hardee, a relative of “Tactics” Hardee,” an officer in the Confederate army. Hardee claimed that the cargo was his and asserted that he was taking it to Savannah. Union authorities, however, seized the ship, detained the crew, and held Hardee and one other prisoner in Fort Taylor until they could be transferred to New York.

U.S. authorities occasionally sentenced unruly Union soldiers from the mainland to imprisonment at Key West. On June 2, 1862, the New York Times reported that twenty-four men from the Engineering Department, under the command of General David Hunter at Port Royal, South Carolina, arrived at Key West on the schooner Isaac M. Holmes. The men had struck for higher wages and refused to work until their demands were met. Upon arrival at Key West, the offenders learned that they would be held at Fort Taylor, and that a military guard would escort them to town to perform their “appointed labor for the day” on the public works as punishment, instead of for pay.

In January 1864, the Sunbury (PA) American reported that several northern dissidents served sentences at Fort Taylor. Union authorities arrested this collection of draft resistors during the July 1863 New York Draft Riots and sentenced them to hard labor to complete Fort Taylor and Key West’s two Martello towers. The prisoners vowed to “rule Key West” and, upon arrival, attacked a gentleman, abused the man’s black servants, stoned his house, and threatened his wife. Union authorities then sentenced the unruly men to six-months imprisonment at hard labor at Fort Jefferson.

Sometimes Union soldiers stationed at Fort Taylor caused disorder. On March 9, 1863, the New York Tribune reported that a few members of the 90th New York Volunteers, on duty at Key West, proved traitorous. Colonel Joseph Morgan, commanding the island at the time, took away swords from the men who were “recreant to their duty,” and sent them to Fort Taylor until U.S. authorities at Hilton Head summoned them for court martial.

Despite their efforts, U.S. authorities could not completely stamp out Confederate sympathy at Key West. In June 1862, the New York Times reported on the arrest, by order of General David Hunter Commander of the Department of the South, of Key West lawyer, Winer Bethel, and prominent merchant, William Pinckney. The Times denounced their participation in Florida’s secession movement, their open Confederate sympathy, and their rejection of the U.S. Admiralty Judge in favor of a “bogus” judge who would have favored the Confederacy. Bethel and Pinckney took the U.S. oath of allegiance, but the paper doubted that they were “sincerely penitent for their offences.” Bethel and Pinckney faced several months imprisonment at Fort Taylor in close confinement, after which U.S. authorities sent them to Fort Monroe, where they were held for nearly a year.

In January 1862, a New York Herald correspondent reported that despite Maj. William French’s order requiring civilians to take the U.S. oath of allegiance, some Key West residents insulted U.S. authorities and flew the Rebel flag over their stores and houses. U.S. officials nabbed W.D. Cash, employed at the Wall & Company Store on an accusation made by Noah Lewis, a black drayman. Lewis reported that Cash made treasonable statements, including a wish that every Union officer and soldier would die of yellow fever. Union authorities held Cash in Fort Taylor for about two weeks without trial. Eventually Col. Joseph Morgan offered to release Cash if he would sign a parole of honor, which he hesitantly did. Other store owners violated the ban on liquor sales. The Provost Marshal destroyed the liquor, closed their shops, and held them in close confinement at Fort Taylor.

Union authorities frequently used Fort Taylor to punish illegal trade. Many offenders came from outside of Key West, especially from Cuba and the Bahamas. One example was Tampa resident James McKay who, before the Civil War, operated a profitable cattle trade on his steamship, the Salvor, in between either Tampa Bay or Charlotte Harbor and Cuba. On October 14, 1861, the crew of the U.S. steamer Keystone State, aware that McKay was likely up to no good, detained the Salvor about twenty miles south of the Tortugas. U.S. authorities confiscated cargo that included 600 pistols, 500,000 percussion caps, 600 dozen hats, eight cases of shoes, 400,000 cigars, 400 bags of coffee, and several cases of dry goods. Union officials sent McKay, passengers R.H. Barrett, W.G. Ball, and local merchant Charles Tift to Fort Taylor.

McKay presented his case to Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas after two-months imprisonment at Fort Taylor. He emphasized his innocence, pleaded for release, and begged Union authorities to also release his fifteen-year-old son who was held at Fort Lafayette. After determining that there was not enough evidence to indict McKay for treason, Major B.H. Hill, commanding at Key West, and U.S. District Court Judge William Marvin, ordered McKay’s release provided he would report to Secretary of State William Seward at Washington, D.C.

McKay secured his release, but prisoner Alphonse Laurent was not as fortunate. Laurent was captain of the British schooner Isabel, which the U.S. gunboat James L. Davis captured. Laurent and his crew were taken to Key West and then released, so he traveled back to Havana to ask the British consulate for reparations for damages. British authorities sent him back to Key West with a copy of his protest and authorized him to have the matter addressed. Union authorities arrested Laurent upon his arrival. Laurent demanded to know his offense, but officials refused to state one. He asserted that U.S. authorities treated him “roughly,” denied him communication with his family in Havana, took his possessions, and forbade him from getting clothes suitable for cold weather in preparation for transfer to Fort Lafayette. These measures were standard treatment for POWs but seemed rough to Laurent. U.S. authorities, however, suspected Laurent of running the blockade and considered him a POW despite his claim of protection from the British Crown.

Union soldiers arrested other blockade runners while they roamed Key West. In June 1863, one New York Times correspondent at Key West denounced blockade runners as “a set of men who seem to have laid aside their sense of moral obligation and responsibility.” Those awaiting interview with authorities sometimes congregated in public spaces and schemed against U.S. authorities, which had an “unwholesome” effect at Key West since it encouraged other Confederate sympathizers to become blockade runners. The Times correspondent was relieved to see them thrown into Fort Taylor, which served as “a wholesome restraint.”

The last newspaper account of prisoners held at Fort Taylor appeared in the New Orleans Times Picayune on November 23, 1865. News of the Confederate surrender failed to reach the high seas. Confederates, Captain Fitz Mohl, General Frank Anderson, Captain Pratt, and Mr. McCormick, who were well-known on the Texas coast, landed at Cape Sable, Florida and learned of the Confederate defeat from U.S. soldiers. Adjutant General of the Army Colonel Edward Townsend ordered the men to close confinement in Fort Taylor for two months.

As a historical relic in Florida’s State Park System, Fort Taylor sees tourists, history buffs, and the just plain curious wander through its confines where, during the Civil War, troops were stationed, blockade runners were held, and Secessionist sympathizers detained. The former “Gibraltar” of the Gulf, however, can still tell its story to those willing to stop and listen as it boasts of its role as a Union stronghold in the deepest part of the Confederacy.

Further Reading:

- Key West: The Old and the New. A Facsimile Reproduction of the 1912 Edition with Introduction and Index by E. Ashby Hammond by Jefferson B. Browne

- Captain Brannan's Dilemma: Key West 1861 by Vaughan Camp, Jr.

- The Fort Zach Guidebook by Edward L. England

- Fort Zachary Taylor: A Sleeping Giant Awakens by Howard S. England

- A Sketch of the History of Key West, Florida A Facsimile Reproduction of the 1876 Edition with Introduction and Index by Thelma Peters by Walter C. Maloney

- Key West: History of an Island of Dreams by Maureen Ogle

- History of Key West by Louise V. White & Nora K. Smiley

- Stronghold of the Straits: A Short History of Fort Zachary Taylor by Ames W. Williams