"The Leader of the Herd" by Edwin Forbes (artist).

Florida made enormous material contributions to the Confederate war effort, relative to its population, and was the site of two minor battles, both Confederate victories. Florida was also crucial to the Union war effort. Throughout the war, the U.S. maintained possession of Fort Taylor (Key West, and the island itself), Fort Jefferson (Dry Tortugas), and Fort Pickens (Pensacola), but U.S. troops evacuated Forts McRee and Barrancas on the mainland at Pensacola. Confederate troops ultimately withdrew from Pensacola in May 1862.

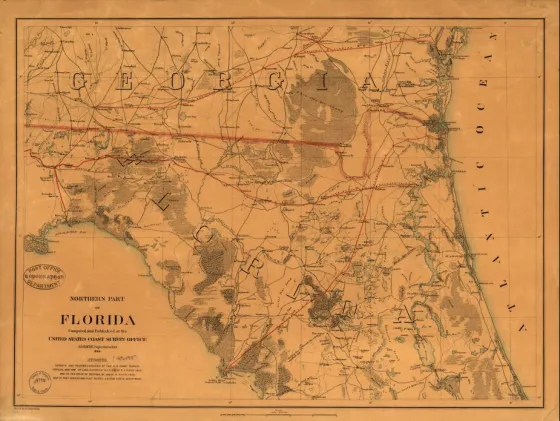

These posts, particularly Key West, which served as the dividing point of the Confederate coastline after President Abraham Lincoln authorized the blockade on April 19, 1861, were critical to the blockade’s effectiveness. After the two initial blockading squadrons, the Gulf and the North Atlantic Blockading Squadrons, were each divided in two, Key West headquartered the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, which spanned from St. Andrew Bay on the west coast to Cape Florida on the east coast and focused particularly on harbors at Cedar Key, Tampa Bay, and Charlotte Harbor and the ports of St. Marks and Apalachicola.

After Florida seceded from the Union on January 10, 1861, Florida state troops seized the federal arsenal at Chattahoochee, Fort Clinch (Amelia Island), Fort Marion (St. Augustine, which later surrendered to Union troops in early 1862), and the Pensacola Navy Yard. The northeastern city of Fernandina was contested by Union and Confederate troops. Confederates abandoned defenses at Fernandina in February 1862, and Union troops occupied the town in March. Tallahassee was the only state capital in the Confederacy east of the Mississippi River to avoid capture by Union troops during the war. Governor John Milton, however, committed suicide in April 1865, rather than facing defeat. Federal troops occupied Tallahassee on May 10, 1865, after the war’s conclusion to facilitate Reconstruction. After the ratification of the 13th Amendment, slaveowners felt the economic impact of emancipation while former slaves defined their freedom by searching for family members sold under slavery and striving for social and cultural autonomy and for civil rights.

During the secession crisis, many Unionists, civilians, and politicians, advocated holding Forts Taylor, Jefferson, and Pickens in the Gulf since they were important to national commerce, but cared little that Florida joined the Confederacy since most of the state was sparsely populated and much of its land remained an undeveloped tropical frontier. Forts Jefferson, Taylor, and Pickens also served an important secondary purpose for the Union as prisons, detaining Prisoners of war, military criminals, Union deserters, Confederate blockade runners, and Secessionists guilty of or suspected of treason.

The Confederate strategy was to hold the state’s interior since its farmland and cattle ranches could supply Confederate troops. Florida’s 1860 population totaled 140,124 (41,128 white men; 36,319 white women; 31,348 male slaves; 30,397 female slaves; 454 free Black men; 478 free Black women), of which slaves constituted approximately 44% while white slave-owners constituted only 3.6%. Most residents were small farmers or worked in jobs not related to agriculture (real estate, lumbermen, fishermen, wreckers, shipping, cattle ranching, day laboring, manufacturing, and professional occupations). Slaveowners from South Carolina and Georgia settled mainly across the Middle Florida plantation belt from the Apalachicola to the Suwanee Rivers and down to around Gainesville, but some also settled around Fernandina, Jacksonville, and St. Augustine along the St. Johns River, around Pensacola in the western panhandle, and on the south side of Tampa Bay.

During the 1860s, Tampa remained a sparsely-populated town. The federal government enticed settlers near the end of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) with the promise of land to settle near Fort Brooke using the Armed Occupation Act of 1842, which offered 160 acres to any white head of family, or single man over 18, who was able to bear arms and provide militia service, farm at least five acres, and live on the plot for five consecutive years. Farther down the peninsula, Florida’s population was even more scarce: Miami’s population scattered due to the Second and Third Seminole Wars (1835-1842 and 1855-1858), Fort Pierce (established in 1838 during the Second Seminole War) saw permanent settlement beginning in the 1860s, and Fort Myers on the Gulf Coast was established during the Seminole Wars, abandoned in 1858, and later became a Union garrison from 1863-1865. In 1860, Florida’s biggest towns were Pensacola (population 2,876), followed by Key West (population 2,832), and Jacksonville (population 2,118), underscoring the importance of seafaring commerce during the 19th century.

Fifteen-thousand Florida men served in the Confederate Army, a significant share of the state’s male population. Ideological support for the Confederacy, however, was not universal. Residents, with the exception of many planters, did not support secession, or at least wanted to wait and see how sectional tensions would play out. Florida’s secession convention voted to secede from the Union on January 10, 1861, by a vote of 62-7. Throughout the war, many residents in the St. Johns River region and in Tampa Bay were opportunists who claimed to support the Union when U.S. soldiers or blockading vessels were nearby, but professed support for the Confederacy either when U.S. troops were absent, or when Confederate troops were present. Some cattle ranchers sold livestock to either the Union or the Confederacy, depending on who paid more. Loyalties were also split in Florida’s port cities, like Key West and Pensacola. Unlike Florida’s rural areas which were home primarily to transplanted Southerners, many settlers in these cities came from the North, and their support for the Union clashed with those who supported the Confederacy.

Many Floridians initially were eager to support the Confederate war effort, but, as the war dragged on, residents rejected measures that the Confederate government imposed. These included the War Tax Act (August 1861), the Impressment Act (March 1863), and the General Tax Act (April 1863). These acts, respectively, levied a small tariff and direct tax on real and personal property; required civilians to contribute part of their livelihood, property (including slaves), supplies, money, and/or crops to the Confederacy; and allowed the Confederate government to impress crops from farmers at a negotiated rate. Civilians received payment in increasingly worthless Confederate States of America notes, given soaring inflation, for complying with the General Tax Act. Governor Milton protested this direct tax, the first of its kind, especially the impressment of milch cows given the dire impact on families.

Men in the ranks also protested through desertion. Over 2,000 Floridians deserted from the Confederate ranks during the war. The war increasingly strained civilians as time went on, leading the Florida General Assembly, in 1862, to appropriate $200,000 to relieve families and $500,000 in both 1863 and 1864. County governments also provisioned the indigent with cotton cards and food rations. Florida’s dire economic situation inspired some civilians to flee to Union blockading ships and profess Unionism, sometimes genuine, sometimes inspired by necessity, especially in 1864.

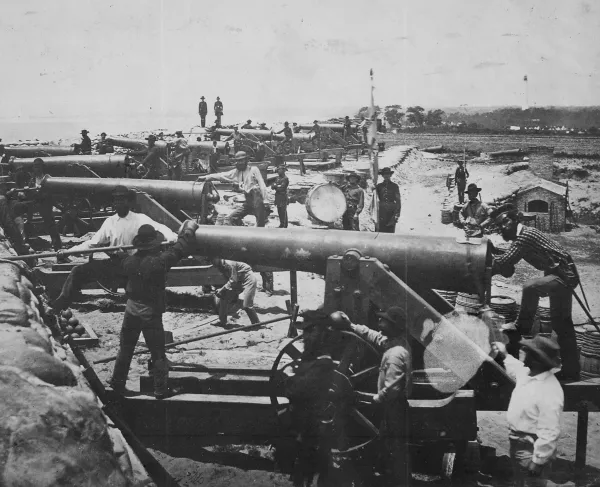

As the war dragged on and U.S. troops closed off access to Texas, Florida became the most important cattle-producing state for the Confederate Army. The 1860 census estimated that Florida possessed 388,060 head of cattle, and the state comptroller reported 658,609 head of cattle in 1862. In 1861 and 1862, Floridians focused on driving cattle from northern counties to transportation lines in Georgia since they were closest in proximity, but the two largest cattle regions were Hillsborough and Manatee counties, which surrounded Tampa Bay. There, many men, who were either in full support of the Confederacy or desired to fulfill the requirement to serve the cause without going to battle, joined the “cow cavalry” to drive cattle from around Tampa Bay up through central Florida to rail lines in north Florida and in Georgia so that meat could reach the Confederate armies in the Eastern and Western Theaters. This was a risky occupation completed largely on foot through swamps, creeks, and dense forests. Beginning in December 1863, drivers had to contend with the United States Second Florida cavalry, a regiment composed of many refugees who had fled to the Union Navy and that engaged in raids on the Gulf coast to stop Florida beef from reaching the Confederate armies. These raids disrupted the organization that the Confederate government hoped to impose in August 1863 by appointing James McKay as regional commissary officer for South Florida. Before the war, McKay operated a profitable cattle-driving business, first driving cows from Tampa to Savannah and Charleston and then shipping them to Cuba. During the war’s early years, McKay contracted with the Confederate government to ship 2,400 steers per month to the Confederate army.

Florida’s military age population, willingly or due to conscription, filled the Confederate ranks. Of the 14,000 - 15,000 men who served in the Confederate armies, one-third became casualties due to combat or disease. After Florida officially joined the Confederacy on February 28, 1861, and the Confederate Army was created on March 6, the Confederate War Department required Florida to contribute men. Five-thousand Floridians filled the Confederate ranks by the end of 1861, leaving the state virtually defenseless. Only 762 militia troops were left to guard Florida’s 54,000 square miles of territory. The state government maintained control over the state militia system and many Floridians, including Governor John Milton, preferred that he, as governor, control Florida’s troops. However, on March 10, 1862, the General Assembly abolished the state militia and Florida was subject to the Confederate Conscription Act (April 16, 1862) which initially included men aged 18-35 and later, 17-52. Some dissidents, like Key West’s Henry Mulrennan, fled the Union-controlled island in 1861. He formed a Confederate unit of mostly exiled Key West and Monroe County residents called the “Key West Avengers” in late 1861. The unit initially defended Tampa against Union blockaders.

Men from Florida, particularly Blacks, also joined the Union Army. Approximately 1,000 Freedmen and 1,200 white men joined the Union Army. One prominent regiment of United States Colored Troops that formed in Florida was the 2nd Florida Cavalry Union. The unit formed at Cedar Key and Key West starting in December 1863, saw service primarily on Florida’s west coast in 1864 and 1865, and mustered out in November 1865.

Some Floridians who did not fill the Confederate ranks or drive cattle established what the U.S. government considered to be illicit salt works to produce this increasingly scarce commodity used to preserve meat for Confederate troops. Florida became one of the most important producers of salt for the Confederacy. Florida’s salt-making industry, at its peak, employed upwards of 5,000 men who received an unofficial exemption from Confederate military service. Some saltworks existed on the Atlantic Coast, but most were on the Gulf between Tampa and Choctawhatchee Bays, including Tampa Bay, Cedar Key, and St. Joseph Bay, the largest being in St. Andrew Bay on the panhandle. Residents set up condensing machines that would, by boiling, extract sea salt from the Gulf’s water to send to the Confederate army. These saltworks became a concerted target of blockading vessels of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron beginning in December 1863, as U.S. sailors sought to strangle the Confederacy of supplies and its ability to support the armies in the field.

As U.S. blockading vessels engaged with civilians on the coast, they not only broke up salt-producing apparatus, but also rescued refugees – Black and white – who fled dangers posed by Confederate sympathizers. These refugees provided intelligence on blockade runners, and U.S. ship captains used them to harass Confederates, destroy saltworks, and/or enlist them in the Union navy. Beginning in late 1862, Egmont Key at the mouth of Tampa Bay, served as an official refuge for Unionists, Black and white, who wished to escape potentially-dangerous Confederate sympathizing neighbors until U.S. ships could transport them to Key West, or other Union-controlled areas.

In addition to seizing refugees, U.S. blockading vessels searched for Confederate blockade-running vessels that transported army stores, foodstuffs, clothing, and munitions from Havana, Cuba, and the Bahamas to Florida’s numerous bays, inlets, and rivers to supply the Confederate Army and transport cotton, turpentine, and tobacco to Caribbean locations for trade. Confederate blockade runners succeeded in ferrying supplies into areas like Tampa Bay, but Florida’s lack of ground transportation made it difficult for materials to reach Confederate troops.

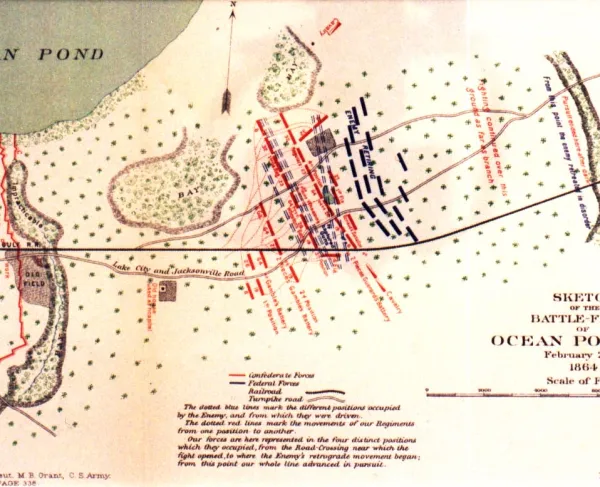

As Florida’s importance as a supplier of the Confederacy increased, the Union Army stepped up efforts to control the peninsula. In 1862, Federal forces seized Fernandina and Jacksonville on the northeast coast, Cedar Key on the northwest Gulf Coast, and Apalachicola on the panhandle, and took control of Tampa in 1864. In 1864, Union troops suffered defeats at the Battle of Olustee (February 20, 1864) at the railroad junction of Gainesville (August 17, 1864) and at Natural Bridge (March 6, 1865) on the St. Marks River south of Tallahassee.

With the Confederate war effort in dire straits and Federal forces near Tallahassee, Governor John Milton committed suicide, shooting himself on April 1, 1865, at his plantation in Sylvania, approximately 36 miles north of Panama City, Florida. Union troops prepared to occupy Florida and the defeated Confederate states and arrested Secretary of the Confederate Navy Stephen Mallory, Governor Abraham Allison, and former U.S. Senator David Yulee who was implicated in facilitating the escape of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

After Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson appointed Judge William Marvin, a Unionist who had served as a judge in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida and, upon his resignation on July 1, 1863, as mayor of Union-controlled Key West, as provisional Governor of Florida (July 13, 1865-December 20, 1865). U.S. troops required elite former Confederates to take the oath of allegiance, paroled Confederate soldiers, and ensured that slaves in Florida were free after Congress passed the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865 (ratified by the stated December 6, 1865). Former slaves pushed for equality and civil rights while the Florida legislature, beginning in 1866, restricted the rights of Freedpeople by passing Black Codes.

Overall, Florida paid a significant price for the Civil War. At least 5,000 Floridians died in battle or from wounds and disease, and civilian loss in property, including slaves, was approximately $44,669,302, not counting raids, scorched-earth policies, and natural deterioration of property. After the war, civilians sought to memorialize Florida’s contributions to both the Union and the Confederacy by erecting monuments in several towns throughout the state including, but not limited to, Jacksonville, Key West, Fort Myers, Tampa, St. Petersburg, Orlando, and Miami.

Further Reading:

- Tampa in Civil War and Reconstruction By: Canter Brown, Jr.

- Tampa Before the Civil War By: Canter Brown Jr.

- Blockaders, Refugees, & Contrabands: Civil War on Florida’s Gulf Coast, 1861-1865 By: George E. Buker.

- The Civil War and Reconstruction in Florida By: William W. Davis.

- Recalling Deeds Immortal: Florida Monuments to the Civil War By: William B. Lees & Frederick P. Gaske.

- Jacksonville’s Ordeal by Fire: A Civil War History By: Richard A. Martin and Daniel L. Shafer.

- Tampa Town: Cracker Village with a Latin Accent By: Anthony P. Pizzo.

- Florida’s Civil War: Terrible Sacrifices By: Tracy J. Revels.

- Thunder on the River: The Civil War in Northeast Florida By: Daniel Shafer.

- Florida in the Civil War The Civil War History Series By: Lewis N. Wynne and Robert Taylor.

- “Paradise Lost: Florida’s Egmont Key During the Civil War” By: Angela Zombek.

- “Confederate Impressment During the Civil War” By: Mary DeCredico.

- Tax History Museum: 1865-1865 – The Civil War.

- 1860 Census: Population of the United States.

Related Battles

148

26