Fort Blakeley and Spanish Fort

Without a doubt, Rear Adm. David G. Farragut’s audacious battle to take Mobile Bay in August of 1864 is one of the most famous actions of the Civil War, and while Mobile Bay had been closed to blockade-running traffic since August 1864, the city of Mobile remained under Confederate control well into 1865.

In the wake of William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea and his Carolinas Campaign, and John Bell Hood’s disastrous middle Tennessee Campaign, Union forces largely had free reign to mop up Confederate resistance. By March 1865, Union Maj. Gen. Edward R. S. Canby prepared to advance on the remaining Confederate strongholds along the Gulf of Mexico coast, and the city of Mobile was one of Canby’s targets.

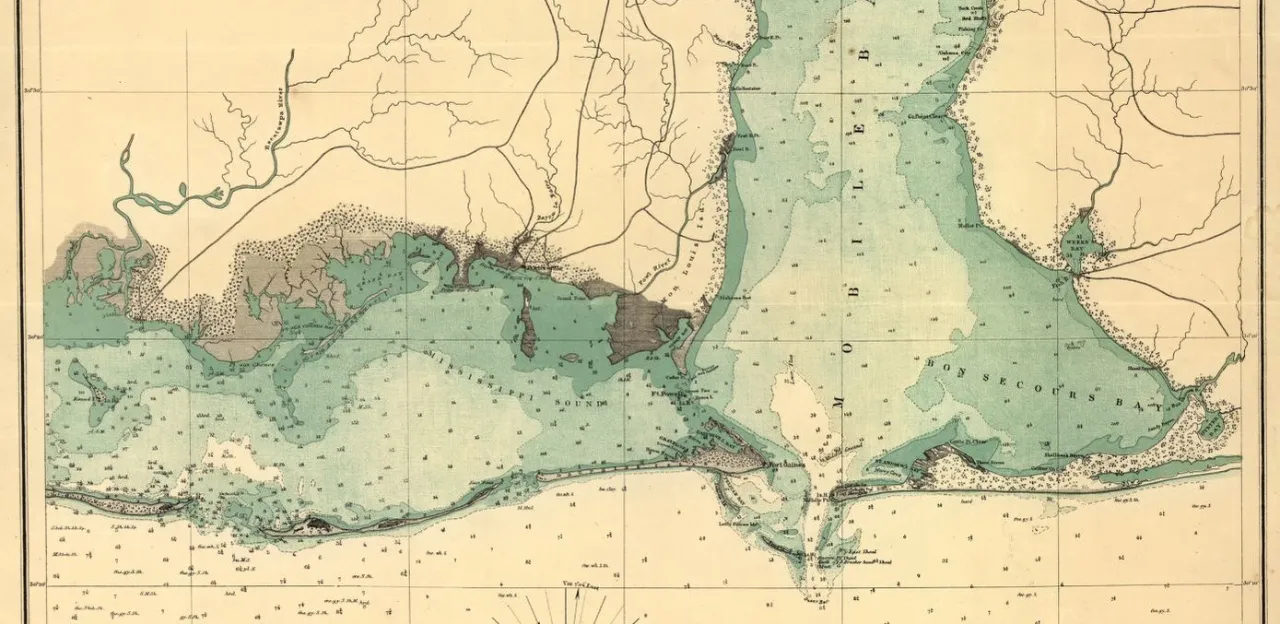

Key to the defenses of Mobile were two Confederate posts on the eastern shore of Mobile Bay: Spanish Fort, directly opposite the city, and Fort Blakely (also spelled Blakeley), five miles to the north. Spanish Fort was occupied by about 3,000 men and mounted 47 guns behind earthen redoubts. Many of those guns were trained westward across the bay, and nearby swamps and frequent high water prevented construction of substantial defenses outside the main fort. Nearby Fort Blakely, at the mouth of the Blakeley (now the Tensaw) River, was manned by 2,500 men and around 40 guns. The three-mile-long earthen fortifications were defended by veteran soldiers. A series of nine earthen redoubts fronted by abatis and felled trees were supported by primitive land mines and telegraph wire strung between tree stumps. Confederate Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell commanded the garrison there and was the senior commander of both forts.

In the last week of March, two Federal infantry columns converged on both garrisons. One column, commanded by Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele, moved northwest from Pensacola, Florida, with orders to take Fort Blakely from the rear. Canby’s XVI and XIII Corps moved north from the coast along the eastern shore of the bay and approached Spanish Fort from the south. By March 27, Canby had encircled the Confederate defenders there and, after a brief firefight, ordered his men to dig in rather than risk a frontal assault. Three armored gunboats, the CSS Nashville, CSS Huntsville, and CSS Morgan, supported the infantry inside Spanish Fort by lobbing shells into Canby’s lines as his men entrenched.

After a week of inconclusive digging and sniping, Canby had surrounded Spanish Fort with around 90 guns. On April 8, an artillery barrage preceded an attack on the lightly defended northern edge of the fort. The follow-up Union attack was enough to dislodge the defenders, and the fort was evacuated that evening. Many of the Confederates fled to Mobile, and around 1,000 escaped into Fort Blakeley to the north. Canby's men rounded up around 500 prisoners as he set his sights on Blakely.

Steele’s column from Pensacola had arrived outside Fort Blakeley on April 1 and laid siege to the garrison for a week. Joining Steele’s men, Canby concentrated around 16,000 men for an attack on the fort on April 9. Included in Canby’s force were around 5,000 United States Colored Troops, one of the largest concentrations of USCTs in the entire war. The Union assault began around 5 p.m. Heavy hand-to-hand fighting raged all along the defensive line. The Union's overwhelming numbers eventually breached the Confederate earthworks, compelling them to capitulate after a brief but intense fight. Liddell surrendered his men to Canby just six hours after Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Virginia.

The siege and capture of Fort Blakeley was the last major battle in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. The mayor of Mobile surrendered the city without a fight on April 12, and all Confederate forces in the area surrendered to Canby on May 4.

Related Battles

322

1,500