Yorktown Battlefield, part of Colonial National Historical Park Yorktown, Va.

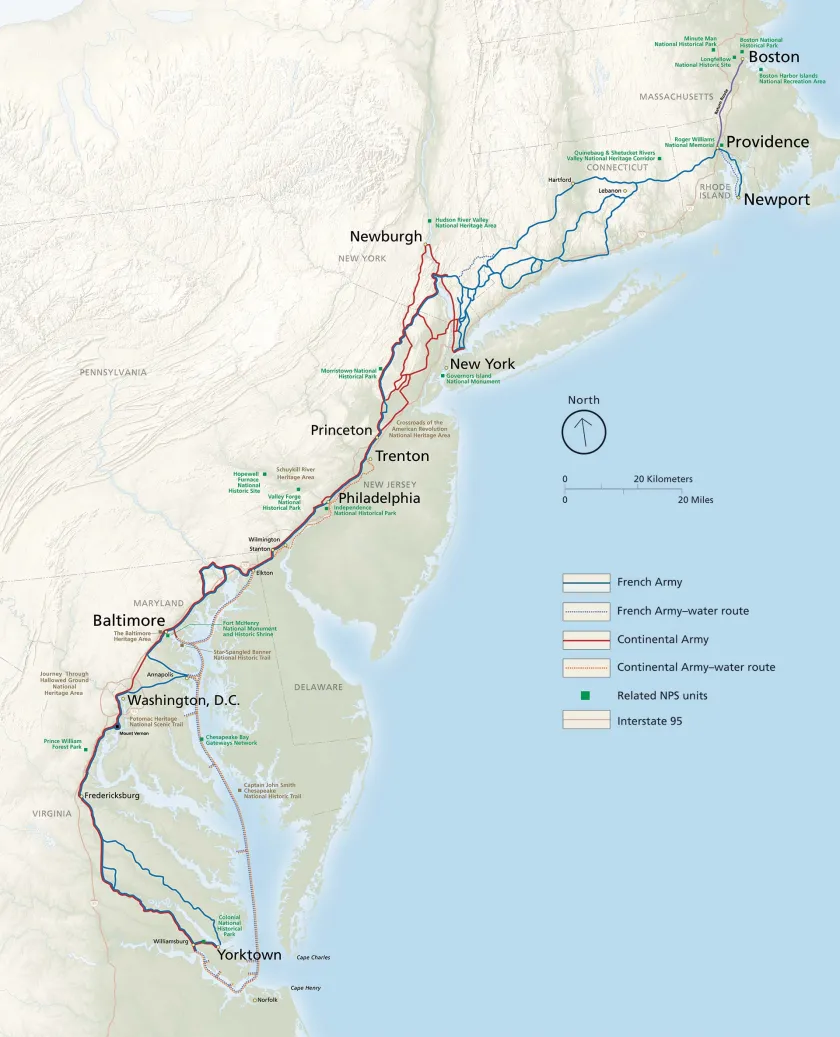

Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail was created in March 2009, making it the youngest of the 19 national historic trails (NHTs) in the National Park Service (NPS) system. It began as a private-public effort in Connecticut in 1995 with the eventually successful attempt to preserve and protect the Rose Farm in Bolton, site of two encampments of French forces under the comte de Rochambeau from June 21 to 25, 1781, and November 4 to 5, 1782, from commercial development. In October 2000, it became a national effort with the passage of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Heritage Act of 2000, which required "the Secretary of the Interior to complete a resource study of the 600-mile route through Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia, used by George Washington and General Rochambeau during the American Revolutionary War:'

Thus the route is designed is to tell the story of the movements of Continental army and allied French forces from bases in New York and Rhode Island south to Yorktown, how this journey contributed to the British surrender on October 19, 1781, and how Patriot and French troops returned north again, the Continental army in November and December 1781, and French forces in July and August 1782.

The themes, goals and unifying purpose of the route are defined by the National Trails System Act of 1968, which requires NHTs to "follow as closely as possible and practicable the original trails or routes of travel of national historical significance;' and by the NPS Final Review Document of October 2006, which states that the route is to "serve interpretive, educational, commemorative, and retracement purposes through recreational, driving, and water-based routes:' The route's intent is to preserve and interpret campsites, surviving road sections, buildings and other architectural or landscape features.

This goal was achieved through resource studies and site surveys for the nine states and the District of Columbia through which the NHT runs. The studies, beginning in Connecticut in 1999, and ending in New Hampshire in 2018, were funded by various public and private donors, the NPS, and the National Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route Association (W3R-US), a nonprofit corporation incorporated in Delaware in 2003, and its state affiliates.

This research identified hundreds of resources and added the State of New Hampshire, where a number of vessels in the fleet of Admiral Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, charged with transporting French forces to the West Indies, anchored from August to December 1782. Research also showed that, with the exception of battlefields related to the Burgoyne Campaign, allied forces visited or marched across every Revolutionary War battlefield along America's East Coast from Bunker Hill to Newport, White Plains, Morristown, Princeton, Trenton, Germantown, Redbank, Cooch's Bridge and Yorktown. French diaries, journals and letters describing these sites constitute invaluable resources of the appearance of these sites, supplementing American and British descriptions.

The racial, ethnic, linguistic and religious makeup of the Continental army reflected the diversity of the nascent United States. French troops reflected the vast empire from which they originated. As these soldiers met their allies, and the civilian populations through which they marched, their encounters made them aware of who they were in part by showing them who they were not. French observations of life in America, particularly of slavery, of customs, habits and foods, often contain information not found in American sources.

The route provides an opportunity to show how victory at Yorktown, indeed in the War of Independence, could only be achieved through the non-military contributions of thousands of Americans who provided cattle, grain, firewood and lodging, and who served as ferrymen, wagon drivers and guides to the troops marching to Virginia. No single community was large enough to supply the roughly 2,400 Americans and 4,500 French troops commanded by hundreds of officers and accompanied by well over 1,000 servants, riding on at least 1,500 horses and hundreds of wagons drawn by as many as 2,000 oxen as they made their way to Virginia. Access to supplies could only be ensured if the troops spread out across a larger area. The legislation establishing the NHT takes this into account when it defines the route as "a corridor" of multiple routes rather than as a single route.

In 1776, France became to first nation to support the rebellious colonies in their struggle, first clandestinely and then openly after the treaties of February 1778. Few Americans realize the extent of that support or how crucial it was in achieving independence. The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail celebrates that victory and the Franco-American friendship that has endured until today.