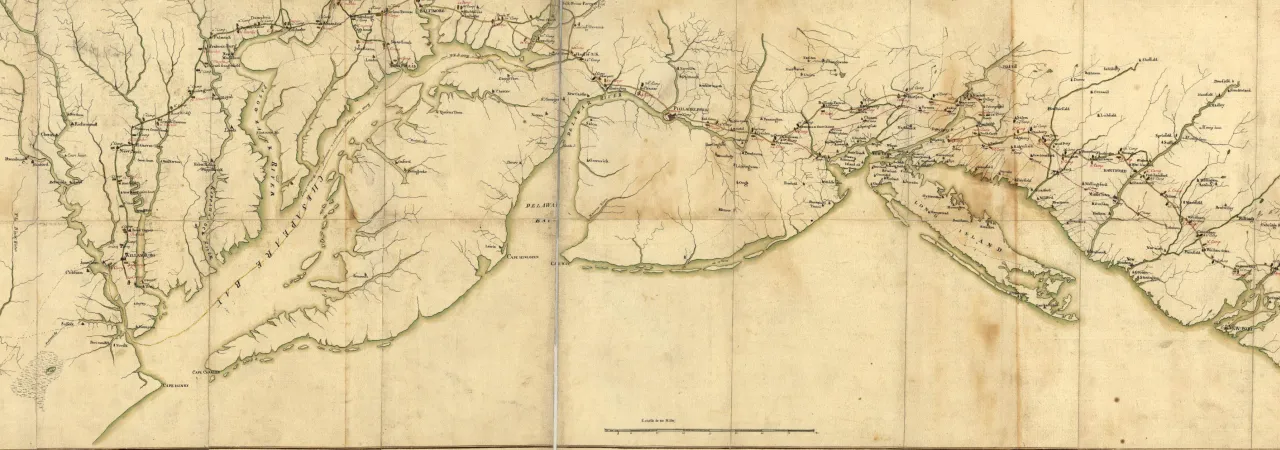

18th-century map of a portion of the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail

France’s support in America’s struggle for independence was crucial in achieving victory at Yorktown. The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail celebrates that victory and the Franco-American friendship that has endured until today. The trail is a 680 mile-long series of roads used by the Continental Army under the command of George Washington and the Expédition Particulière under the command of Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau during their 1781 march from Newport, Rhode Island to Yorktown, Virginia.

History

On April 9, 1781, an almost despondent George Washington informed Lieutenant-Colonel John Laurens in France that "We are at the end of our tether, and that now or never our deliverance must come.” The campaign of 1781 would have to produce results, or the War of Independence might be lost. Yet the deliverance so eagerly sought by Washington was but six months away. The year 1781, a year which had seen the nadir of American fortunes when the Pennsylvania and New Jersey lines mutinied in January, would metamorphose into the annus mirabilis, the “miracle year”, when everything worked out just perfectly. Following an almost 700-mile-march along America’s eastern sea-shore, fortune shone on Franco-American arms at Yorktown where American independence was won.

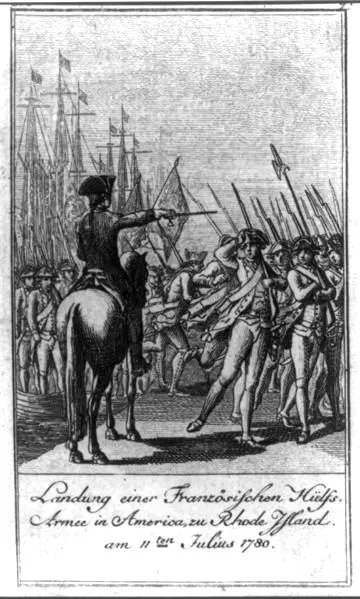

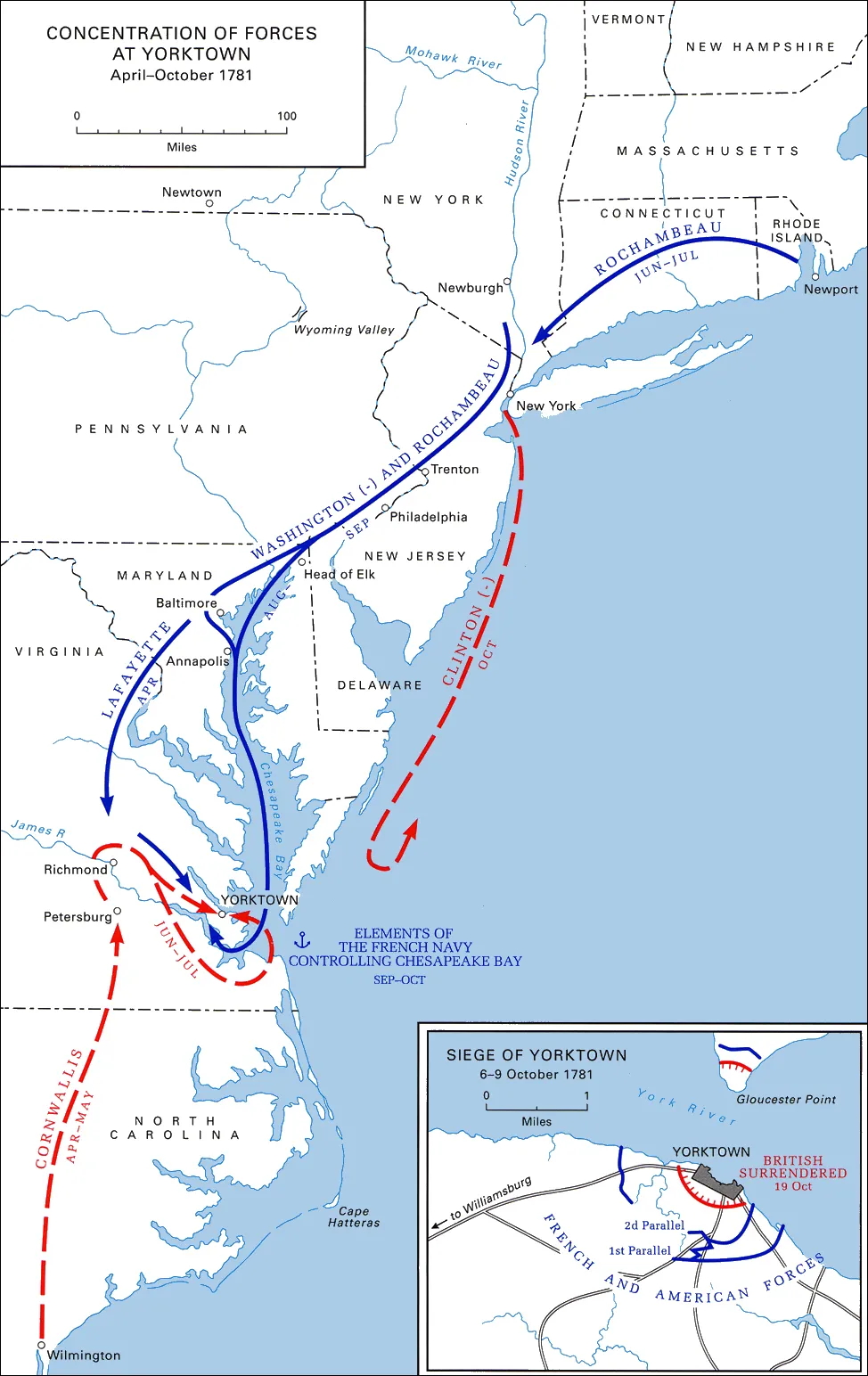

French forces under Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, almost 500 officers and close to 5,000 soldiers in four regiments of infantry, a battalion of artillery and Lauzun’s Legion, a 600-man-strong mixed unit of infantry, artillery and cavalry, had sailed out of Brest on May 2, 1780, and spent the winter 1780-81 in Rhode Island and Connecticut. During their conference at Wethersfield, CT, in late May 1781, Washington and Rochambeau decided to join their forces in Westchester County for the planned siege of New York City, Britain’s center of political and military power on the North American continent. Unbeknownst to Washington, French Admiral François Joseph Paul de Grasse, comte de Grasse, had sailed from Brest for the Caribbean on April 5, 1781, with instructions to provide the naval support for the allied campaign of 1781.

On June 10, 1781, French troops received orders to embark on dozens of small vessels and sail from Newport to Providence, the first leg of the French march that would take them to Yorktown and victory. On Monday, June 18, the Regiment Bourbonnois set out from Providence for Waterman's Tavern on the Rhode Island-Connecticut State Line. The other three regiments followed over the next three days. Concurrently between June 21-23, the Continental Army broke its camp around Newburgh and marched to White Plains in Westchester County just north of New York City. Upon arrival on July 6, 1781, about 6,500 Continental soldiers reported “Present fit for duty & on duty” with another 3,200 “on command” and about 580 “sick present” or “sick absent”. Once Rochambeau’s army had joined them on July 6, the allied camp of around 1,000 officers and 15,000 soldiers plus support personnel, was the third-largest city in the United States behind Philadelphia and New York City. All the two generals could do now was wait for Admiral de Grasse to array his fleet off New York City to close the siege ring and Sir Henry Clinton and his 15,500 officers and men would be trapped.

A reconnaissance in force from July 21-23 convinced Washington that his combined forces were too small for a successful siege of New York City, and when he received word on August 14 that de Grasse was on his way to the Chesapeake he quickly changed plans. On August 18, the allied armies, around 2,650 Americans and 4,650 French were on their way to Yorktown. Thirty-two days later, on October 19, Lord Cornwallis had surrendered his army of around 7,400 officers, soldiers and sailors at Yorktown.

Historic Trail Today

The Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail (the Route) commemorating the allied deployment celebrates not only that victory but the thousands of Americans along that route whose contributions and support made the victory possible. Supplying the roughly 7,300 allied forces, around 1,000 officer’s servants in the French army alone, waggoners for the 210 official French wagons, 110 private wagons of officers, and another 35-40 Americans drawn by six oxen each (~2,100 large animals), hundreds of “hamburgers on the hoof”, ~1,200 horses for the French officers and their servants, 500 artillery horses, 300 horses for Lauzun’s hussars, winding their way in mile-long columns across New Jersey into Pennsylvania and Delaware to Baltimore and Annapolis posed huge logistical challenges. No community other than Philadelphia was large enough to feed these multitudes: Princeton counted fewer than 100 homes, Trenton had maybe 500 inhabitants, Wilmington around 1,400, and when the allied armies camped in Baltimore the population of the town doubled. The Route illustrates the crucial contributions of the states and their citizens toward the victory at Yorktown.

As Continentals and their French allies entered Delaware and Maryland, they entered regions and cultures alien to them. Neither had ever experienced chattel slavery as practiced in Maryland and Virginia, and neither had many Virginians ever met a Massachusetts Yankee or a French soldier. The campaign of 1781 stands as a diverse, cross-cultural - intra-American as well as Franco-American experience that over time became crucial for the development of a national American identity and character. Through these encounters Americans learned about the varied regions of their new nation and who they were by learning who or what they were not.

Lastly, the Route serves to remind Americans of the crucial contributions of France toward American independence and as a manifestation of the global character of that war. Along those hundreds of miles, friendships were formed that became the basis for more than two centuries of Franco-American brotherhood in arms. Preserving that brotherhood both in the collective American memory as well as through the hundreds of campsites, surviving road sections, historical buildings, and other resources in the nine states along the route is the goal of the Route. It is a goal well worth the effort.

Related Battles

389

8,589