Book: The Battle of South Mountain

The Civil War Trust recently had the chance to sit down with John David Hoptak, author of The Battle of South Mountain, a new account of this important 1862 Maryland Campaign battle fought just before the fateful Battle of Antietam.

Civil War Trust: John, your new book, The Battle of South Mountain, is a welcome addition for those who want to learn more about this important 1862 battle. What motivated you to write an account of this battle?

John Hoptak: There were several reasons. Strange as it sounds, growing up as I did studying the Civil War, even from my earliest days I have felt something of an attachment to the Battle of South Mountain simply because I was born on the same day on which it was fought, September 14. Aside from this, being a student of the Federal Ninth Army Corps, South Mountain interested me because the Ninth Corps did all the fighting at Fox’s Gap. Most importantly, however, I decided to write on South Mountain because it has long remained one of those understudied battles of the Civil War, languishing for so long in the shadow of Antietam. Indeed, despite the tens of thousands of Civil War-related titles to have hit the shelves since the cessation of hostilities, only two focus specifically on South Mountain: John Priest’s Before Antietam and Tim Reese’s excellent study of the fighting at Crampton’s Gap titled Sealed With Their Lives, both of which are out of print. My intention with The Battle of South Mountain was to present a succinct narrative history of this important battle, focusing on the action at Frosttown, Turner’s, Fox’s, and Crampton’s Gaps, while at the same time placing the battle within the larger context of the consequential Maryland Campaign of September 1862.

Give us a sense of what both sides were trying to accomplish at South Mountain on September 14, 1862.

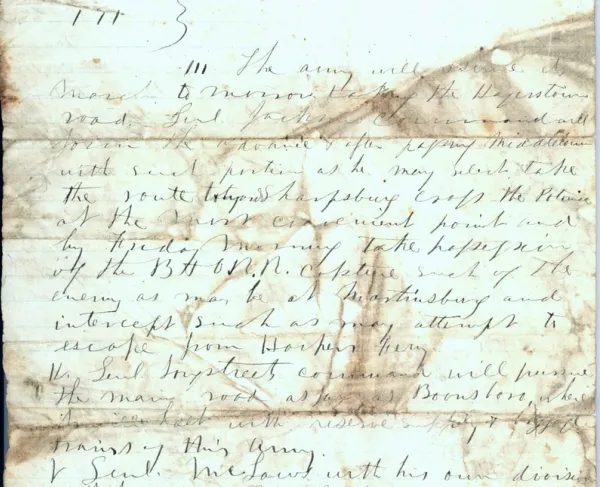

JH: At its most basic level, the Army of the Potomac was attempting to force its way across the mountain in order to carry out George McClellan’s instructions of cutting “the enemy in two and beating him in detail.” Lee’s forces, on the other hand, were simply trying to prevent this from happening. In his drive north across the Potomac, Robert E. Lee originally had no intention of defending the South Mountain passes; he, instead, wanted to draw the Army of the Potomac across and bring it to battle west of the mountain. However, with Lee’s army still dangerously divided on the morning of September 14, in executing the orders and falling behind the timetable spelled out in Special Orders No. 191—with Longstreet’s forces near Hagerstown and Jackson’s at Harpers Ferry—and with McClellan advancing rapidly from Frederick, Lee was forced to defend the mountain. Just ten days into his first invasion of Union soil, Lee lost the initiative and was forced on the defensive.

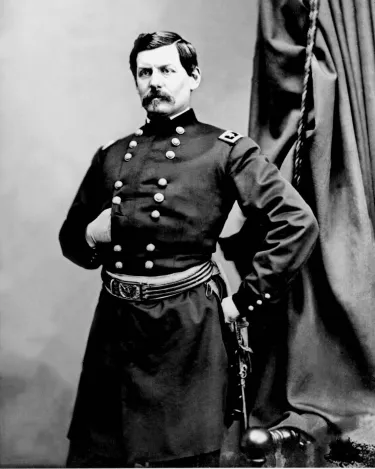

Despite his reputation for the opposite, your account really shows Union general George McClellan as an aggressive and vigilant leader. How would you rate McClellan’s generalship at South Mountain?

JH: George McClellan remains one of the most polarizing and most controversial figures of the Civil War, and I am sure some of what I argue in The Battle of South Mountain will raise some eyebrows.

Yes, I do think he moved much more aggressively during the first stages of the Maryland Campaign than is typically and traditionally described. What gets lost in so much interpretation of the campaign was the tremendous amount of pressure resting on McClellan’s shoulders. Early September 1862 witnessed some of the darkest days the United States would experience during the entirety of the war; spirits were low both in the army and on the home front following a lamentable summer’s worth of defeats, and with two Federal armies driven into the safety of Washington’s formidable defenses. With Confederate forces pushing north across a 1,000 mile front, both in the East, with Lee’s men threatening a drive across the Potomac, and in the west, with Bragg’s and Kirby Smith’s men moving north through Tennessee and into Kentucky, and with Great Britain leaning very close to offering recognition of the Confederate States of America, George McClellan was called upon once again to help sort out the mess, and bring order to the chaos that defined the Federal forces in the East.

With great energy, McClellan immediately went to work, incorporating John Pope’s Army of Virginia into his own Army of the Potomac and organizing the dozens of new regiments arriving daily in Washington, while at the same time preparing for a pursuit of Lee’s columns into Maryland. No easy task, yet one McClellan tackled admirably. Of course, McClellan could not know where Lee was headed, but nonetheless did a good job in organizing the pursuit. What aided McClellan in his pursuit of Lee was the fact that Confederate Cavalry general Jeb Stuart did not do a good job in keeping Lee up to date on the movements of the Army of the Potomac. Lee was almost lulled into a false sense of complacency.

On September 8, Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis from Frederick that as far as he knew the Union army was still gathering in the defenses of Washington. Yet by this date, McClellan was already well on the way out of the city; the following day, the same day Lee issued Special Orders No. 191, the Army of the Potomac was already halfway between Washington and Frederick. McClellan learned of the Confederate evacuation of Frederick and picked up the pace of the Federal pursuit so that by the evening of September 12, his leading forces were arriving in the Maryland city. His orders to Burnside, commanding his right wing, and to Pleasonton, his cavalry chief, were to continue pushing west the following day. Thus, when McClellan was handed the lost copy of 191, his advanced forces were nearly already at the foot of South Mountain. Special Orders 191 made clear that Lee has divided his forces and McClellan planned to exploit this by ordering his men to force their way across South Mountain. While Burnside with the right wing—the First and Ninth Corps—were to keep the Confederate “main body” at bay at Turner’s Gap, William Franklin’s Sixth Corps was instructed to punch through six miles south at Crampton’s Gap, destroy McLaws’s force of Maryland Heights and thereby lift the siege of Harpers Ferry. This is one example of the aggressiveness, if you will, of McClellan’s orders for September 14, for in order for Franklin to carry out these instructions, he had to first leave the Sixth Corps’s bivouac site at Buckeyestown, march no less than thirteen miles, across the Catoctin Mountains, battle their way through Crampton’s Gap at South Mountain, then turn south, destroy McLaws and then turn around, and move north to assist Burnside. Nothing about this says “caution” to me. I’m sure there’ll be those who disagree with this assessment, but that’s the purpose of studying history. My job is neither to vilify nor defend McClellan or any other commander, just to call it as I see it, as best I can.

The Battle of South Mountain featured fierce fighting at three different rough mountain passes. What was the solider experience like at this battle?

JH: The terrain over which these soldiers fought at South Mountain was incredibly difficult, particularly at Frosttown Gap, which was defended by Robert Rodes’s Alabamians and attacked by Hooker’s First Corps. As Hooker noted, the mountain was difficult to ascend “even in the absence of a foe in front.” Lee’s men may have been outnumbered, but at Frosttown, Turner’s, and Fox’s Gaps, they did enjoy a strong defensive position. When visiting the battlefield today, it is sometimes impossible to imagine that soldiers actually fought there. It is no easy climb. One can also get a sense of the difficulty in maintaining orderly formations, because of the ground, because of the confusion of battle, and so on. In many cases, especially at Frosttown and Crampton’s Gaps, the fighting bogged down into small unit actions, with squads of victory-flushed Union soldiers advancing ahead of others, with Confederates retreating pell-mell up the mountain slopes; all was confusion, all was chaos. The fighting even extended well after night fell; the bright muzzle flashes briefly illuminating the darkness, with the pitiable cries and groans of the wounded, with the men groping about in the dark seeking their companies. It is all impossible to describe.

Did Robert E. Lee choose South Mountain as a place to give battle? How would you rate the Army of Northern Virginia’s leadership at this battle?

JH: As noted above, Lee felt he had no choice; McClellan forced him to give battle at South Mountain. Lee did not originally intend to defend the mountain passes, but had to lest his army, as McClellan envisioned, be cut in two and destroyed in detail. Regarding Confederate leadership, it should be remembered that Lee never once set foot on the battlefield, the injuries to his hands prevented him from doing so. He thus had to trust in his subordinates. Some, such as D.H. Hill, Robert Rodes, Alfred Colquitt, and Samuel Garland, turned in fine performances, while others, such as Roswell Ripley and even Paul Semmes did not. Of course, as with all officers at every battle, they did the best they could under the circumstances. There was little time for setting up proper defenses and becoming familiar with the terrain. So many of the Lee’s brigades were simply rushed into the fight one at a time, as soon as they arrived on the mountain top.

Did your research of the battle produce any new opinions or subjects of interest related to South Mountain?

JH: As pointed out by my friend Dr. Thomas Clemens, an expert on the 1862 Maryland Campaign who recently edited Ezra Carman’s exhaustive account of the campaign, the fighting at Fox’s, Turner’s, and Frosttown Gaps was largely Ambrose Burnside’s show. As commander of the right wing, Army of the Potomac, Burnside orchestrated an impressive double-envelopment of the Confederate position on the mountaintop, with Reno’s Ninth Corps attacking the Confederate right and Hooker’s men striking at the Confederate left, while John Gibbon’s famed “black hat” brigade probing the middle. From above, Burnside’s attack must have resembled a large pitchfork, with his blue columns sweeping up the difficult mountain terrain. One wonders how much of this Lincoln paid attention to; was it to him more evidence of Burnside’s tactical/strategic leadership, his soundness for command he demonstrated earlier in the year in North Carolina that first caught Lincoln’s attention? Aside from Burnside’s creditable showing on September 14, it is interesting that during the early stages of this campaign, Jeb Stuart did not turn in all too great a performance in reporting Union troop movements during the early stages of the campaign; indeed, his scarcity and even inaccuracy of reports may have lulled Lee into a sense of complacency, believing that time was on his side, even when it was quickly slipping away. Further, while Lee is often, and most of the time justifiably credited with an ability to “read” his opponents, during the campaign, he entirely misjudged McClellan’s rate of advance and had erroneously assumed that the Federal garrisons at Martinsburg and Harpers Ferry would obligingly flee with the movement of his army across the Potomac. Of course they did not, which forced Lee to alter his campaign by dividing his forces. His army fell behind what was an impossible timetable for the completion of the Harpers Ferry expedition and still remained divided on the morning of the Fourteenth, when McClellan attempted to force his way across the mountain.

Victorious at South Mountain, did McClellan and the Union Army miss an opportunity to strike a divided Army of Northern Virginia before they actually met at Antietam on September 17th?

JH: There is no question that South Mountain was a Union victory, in the tactical sense. They drove Lee’s men off the mountain and compelled Lee to order a retreat on the night of September 14, not only of his forces on the mountain, but of Jackson’s forces at Harpers Ferry as well. Lee thus decided that night to abandon his northern campaign. However, as the hours ticked by the following morning, on Monday, September 15, the fruits of the Union’s hard-won victory began to wither. Yes, there were several missed opportunities, especially early on September 15. But the blame for these missed opportunities cannot rest entirely on McClellan’s shoulders. McClellan wanted a vigorous pursuit on the morning of September 15, and was still hoping to left the siege of Harpers Ferry. His orders were to move out at daybreak and strike at Lee’s columns, if they were found to be on the march. It was his subordinates, instead, who let him down. William Franklin, in Pleasant Valley, did not so much as budge that morning. McClellan wanted him to push south through the Valley and destroy McLaws’s isolated command; doing so, would have lifted the siege and may have led to the destruction of a full twenty percent of Lee’s army. Instead, Franklin, convinced he was up against tremendous odds, did not do so. Harpers Ferry fell, which allowed McLaws’s force to cross the Potomac and escape. McClellan also ordered Burnside to have the Ninth Corps on the road at 8:00 a.m., in pursuit of D.H. Hill’s and Longstreet’s retreating columns. But by noon, the Ninth Corps still remained at Fox’s Gap. When McClellan arrived on the high ground east of the Antietam late that afternoon and examined Lee’s strong line of defense on the heights on the other side of the creek, only a portion of his army was on hand and it was too late in the day, he decided, to mount any further offensive action.

The South Mountain Battlefield features some of the most interesting topography of any Civil War battlefield. What are some of your favorite places to visit at South Mountain?

JH: The South Mountain battlefields are certainly worth a visit; I urge everyone with an interest in the Civil War to head on out to these fields. There are some portions of it that are a little difficult to navigate. Because of the terrain and because the battle was so spread out—I like to say the battle was fought on three islands, separated by miles from one another—it is also sometimes difficult to get a sense of the entirety of the action. There is virtually no commercial or any other kind of development there, so in that sense at least little has changed. I have long enjoyed visiting Fox’s Gap and standing at the Reno Monument, which marks the spot where the beloved commander of the Ninth Corps received his death wound. It is quiet there and, I must admit, an eerie sense that this battle “just happened” often overtakes me. The same can be said when I travel to Burkittsville and travel along Mountain Church Road, where the main Confederate line defending Crampton’s Gap was positioned. Looking across the expansive farmland to the east of this roadway, it is easy to picture the massive blue waves sweeping directly toward you—the men of Slocum’s division, who suffered heavily in their attack. In some places, the original stone walls that lined this roadway still stand. The War Correspondents Memorial Arch—a very interesting memorial—atop the mountain at Crampton’s Gap is worth a visit as is the Washington Monument north of Turner’s Gap, which was the first monument in the nation built and dedicated to the memory of our first president. Be sure also to stop on by the Visitor Center. The battlefields are situated along the Appalachian Trail, for those hikers out there, or for anyone wishing to enjoy a pleasant, a peaceful stroll through history.

How has the South Mountain battlefield changed since 1862? Looking forward what would you love to see happen at South Mountain from a preservation or interpretation point of view?

JH: Excepting increased tree coverage and vegetation in some portions of the battlefield, very little has changed. As mentioned above, there is little commercial development that has impacted the battlefield. The good news—very good news—is that the South Mountain State Battlefield, as of January of this year, has been added to National Register of Historic Places, and our thanks are due to John Miller, Robb Bailey, Isaac Forman, Paul Miller, and everyone else for their efforts for making this happen. It is also my understanding that more than 100 acres of important battlefield ground has recently been acquired by the Battlefield, mostly in the areas to the north of Bolivar, where Meade’s division of Pennsylvania Reserves formed their attack against Rodes’s Alabamians. Other acreage recently acquired includes a part of the field where Garnett’s Virginians struggled against the Federals of John Hatch’s Division. Within the past few years, there has been a partnership established between the South Mountain State Battlefield and the Antietam National Battlefield. All of this is very good news. Special events and programs are currently being planned for the Sesquicentennial Commemoration of the battle. It is clear, then, that there has been an increased awareness of the importance of this battle and of these battlefields. As far as looking ahead, I would like to see this awareness continued, for increased awareness will bring about increased preservation. And these fields need to be preserved and the story of what happened there needs to be known.

Buy the Book: "The Battle of South Mountain" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

John Hoptak was born on the 116th Anniversary of the Battle of South Mountain, on September 14, 1978, in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. A lifelong student of the American Civil War, Hoptak holds a bachelor's degree in history from Kutztown University and a master's in history from Lehigh University. He currently serves as an Interpretative Park Ranger at Antietam National Battlefield, and as an adjunct instructor at American Military University, where he teaches courses in American history, Civil War history, and Mexican-American War history. In addition to The Battle of South Mountain, Hoptak is the author of several of other books, including First in Defense of the Union: The Civil War History of the First Defenders (2004), Our Boys Did Nobly: Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, Soldiers at the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam (2009), and Antietam: September 17, 1862 (2011). He is a long-time member of the Civil War Trust and is dedicated to the preservation of Civil War history. Hoptak led the effort to restore the 48th Pennsylvania Monument at Antietam National Battlefield by conducting a nationwide initiative to restore the missing sword from the statue of Brigadier General James Nagle, an effort successfully completed in 2010.