Over the course of the Civil War, an estimated 476,000 soldiers were wounded by bullets, artillery shrapnel, or sabers and bayonets. The most common wounds suffered by Civil War soldiers were from the bullets fired by muskets. The typical bullet fired was called a Minnie ball, a conical bullet with hollowed grooves. Weighting 1 ½ ounces the large bullets (.58 caliber) were propelled relatively slowly by the black power charge. When it struck a human, the ball caused considerable damage, oftentimes flattening upon impact. Minnie balls splintered bones, damaged muscle, and drove dirt, clothing, and other debris into the wounds. As a result of the immense damage inflicted by Minnie balls, amputations were common during the Civil War.

An amputation is a surgical procedure that removes a piece of the body because of trauma or infection. Over the course of the Civil War, three out of four surgeries (or close to 60,000 operations) were amputations. This earned surgeons throughout the armies a reputation of being “butchers” when in fact amputations were one of the quickest, most effective ways for surgeons to treat as many patients as possible in a short amount of time. The medical director of the Army of the Potomac, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, was well aware of the criticisms of surgeons in the field and wrote in his report after the Battle of Antietam:

The surgery of these battlefields has been pronounced butchery. Gross misrepresentations of the conduct of medical officers have been made and scattered broadcast over the country, causing deep and heart-rending anxiety to those who had friends or relatives in the army, who might at any moment require the services of a surgeon. It is not to be supposed that there were no incompetent surgeons in the army. It is certainly true that there were; but these sweeping denunciations against a class of men who will favorably compare with the military surgeons of any country, because of the incompetency and short-comings of a few, are wrong, and do injustice to a body of men who have labored faithfully and well.

There were several types of wounds that required an amputation according to medical military manuals, including “when an entire limb is carried off by a cannon-ball leaving a ragged stump; also if the principal vessels and nerves are extensively torn even without injury to the bone; or if the soft parts (muscle) are much lacerated; or in cases of extensive destruction of the skin”. However, when amputation was necessary, the limb was not simply “chopped off” as commonly believed. The procedure was sophisticated, and like most surgical procedures over the course of the war, were conducted with patients under anesthesia in the form of either chloroform or ether.

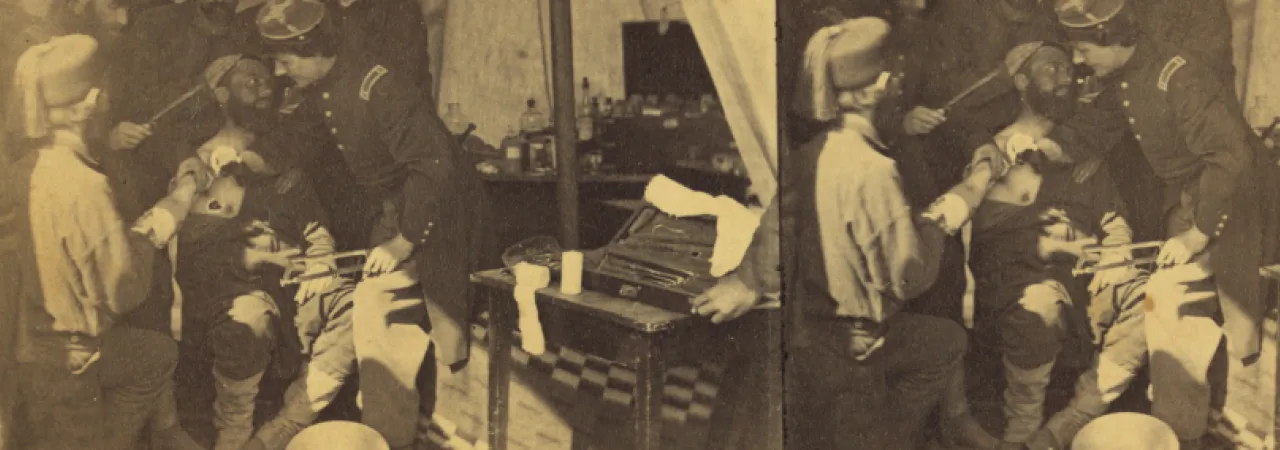

Before undergoing an amputation, a tourniquet was tightened around the limb in order to reduce bleeding when the damaged limb was removed. The surgeon began with either circular or flap amputation procedure. A circular amputation cut through the skin, muscle, and bone all at the same point on the limb creating an open wound at the stump that healed on its own. It proved the simplest and fastest method of amputation, but it took longer to heal. The flap method used skin from the amputated limb to cover the stump, closing the wound. This surgery took longer but healed faster and was less prone to infection. Whenever possible surgeons opted for the flap method.

During an amputation, a scalpel was used to cut through the skin and a Caitlin knife to cut through the muscle. The surgeon then picked up a bone saw (the tool which helped create the Civil War slang for surgeons known as "Sawbones") and sawed through the bone until it was severed. The limb was then discarded, and the surgeon tied off the arteries with either horsehair, silk, cotton, or metal threads. The surgeon then scraped the edges of the bone smooth, so that they would be forced to work back through the skin. The flap of skin left by the surgeon could be pulled across and sewn close, leaving a drainage hole. The stump was then covered with plaster, bandaged, and the soldier was taken aside for the surgeon to start on his next patient.

The chances of survival for an amputation depended on where the amputation was performed and how fast medical treatment was administered after the wounding. Many amputations over the Civil War occurred at the fingers, wrist, thigh, lower leg, or upper arm. The closer the amputation was to the chest and torso, the lower the chances were of survival as the result of blood loss or other complications. Many surgeons preferred to perform primary amputations, which were completed within forty-eight hours of the injury. They had a higher chance of survival rather than intermediary amputations which took place between three and thirty days. Poor nutrition, blood loss, and infection all contributed to the lower survival rates of intermediary amputations after forty-eight hours.

After completing numerous amputations after a battle, medical personnel were left with another problem that needed solving. What to do with the piles of discarded limbs. The sight of a pile of amputated limbs frightened many, contributing to soldiers’ views that surgeons were more “butchers” instead of “doctors”. After the Battle of First Manassas, one Confederate soldier John Opie of the 5th Virginia Infantry remarked that at a field hospital:

There were piles of legs, feet, hands and arms, all thrown together, and at a distance, resembled piles of corn at a corn-shucking. Many of the feet still retained a boot or shoe. Wounded men were lying on tables and surgeons, some of whom at the time were very unskillful, were carving away, like farmers in butchering season, while the poor devils under the knife yelled with pain. Many limbs were lost that should have been saved, and many lives were lost in trying to save limbs that should have been amputated…

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the poet Walt Whitman described the scene of at a Federal hospital at Chatham just across the Rappahannock River:

It is used as a hospital since the battle, and seems to have received only the worst cases. Outdoors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house [probably the still standing Catalpa tree], I noticed a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, etc. -- about a load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each covered with its brown woolen blanket. In the dooryard, toward the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel staves or broken board, stuck in the dirt.

What were surgeons to do with these amputated limbs? Unfortunately, there is not a clear answer for surprisingly little is written about the subject since it was such a striking and sickening sight. Using the little documentary sources available, as well as the archaeological evidence found on the multiple battlefields, it appears that many amputated limbs were buried in mass graves or less likely burned. The struggle of the sight of amputated limbs was not only found at the hospitals, but soldiers had to confront this stigma at home as well.

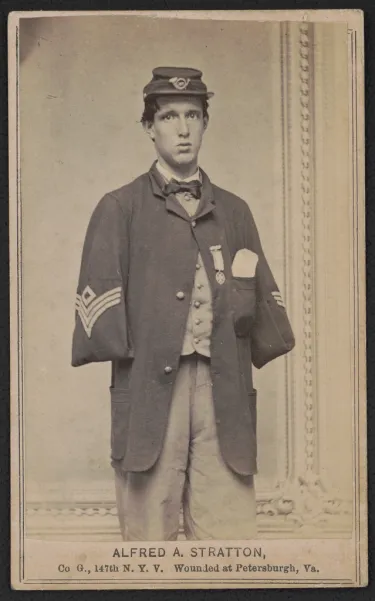

For soldiers who survived amputations, another struggle awaited them at home both mentally and physically. In the 1800s, one of the many marks of manhood was the ability to support one’s family. Having a disability meant that these men were no longer the prominent member of their families, but instead had to rely on others. In the 1800s, men who were not the primary breadwinners of their household had negative implications on one’s moral character, and many such men were seen as a blight on society. In fact, the slang term “invalid” in the 1800s meant person the person wasn’t considered a valid member of society. With the negative prewar stigma related to the loss of limb and the ability to work, many soldiers not only opposed the amputation before the surgical procedure began, but struggled with depression, shamefulness, and finding a meaningful role in society again once they returned home. This created the mounting need for pensions and/or prosthetics for wounded veterans.

A federal pension system was created in 1862 to assist wounded Union veterans. However, the system to apply for a pension was very black and white: either a veteran had the physical capability to work, or they did not. According to the United States Pension Office, disability was defined as the inability to perform manual labor meaning that in order to get what many soldiers believed was a fair payment, they had to swear that they could no longer work at all. For many veterans, this was a huge step to take because it took away their manliness because they had to rely on the government for money to live and support their families. If a disabled soldier decided to apply for a pension, the amount they received on a monthly basis depended on their rank and their injury. For example, a disabled private received just $8 a month (about $205 a month in 2020) from the first pension system. Dependents, such as widows and children, of soldiers who were killed on duty, were also eligible. Because of the negative views of the 1800s around receiving a pension, many veterans did all they could to try and prove that they were able to work.

Many veterans wanted to continue to work after recovering from their wartime injuries, but as a disabled veteran, they were often discriminated against for it was often assumed they could not perform a job as well as an able-bodied employee. As a result, some veterans went through extreme lengths to prove they could work, including learning to write with their left hands for clerical work, as well as relying on prosthetics. Prior to the Civil War, there were few choices for prosthetic limbs for soldiers that needed them. The patents that were available were uncomfortable and not easily functional. As early as 1861, amputees began developing their own improved prosthetics allowing for greater mobility and allowing them to reenter civilian society. One of the first soldiers to undergo an amputation during the Civil War was Private James Hanger of Churchville, Virginia, who lost his leg during the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861. Over the course of the war, he began distributing his new “Hanger Limb” to other soldiers in need and after the war ended, began his own business: the J.E. Hanger Company. Today, Hanger Inc. is one of the leading prosthetic companies today.

The Civil War created thousands of “maimed men” who returned home with empty sleeves and had to readjust to life without the limbs that many take for granted. These men not only had to deal with uncomfortable and painful prosthetics, they also had to come to terms with how they were treated by their family and community. Like many aspects of Civil War medicine, because there were so many cases of amputations, the procedures, recovery methods, quality of prosthetics, and an increased awareness for mental health were all propelled into the modern medicine that many of us take for granted today.

Further Reading:

- A Manual of Military Surgery, for the Use of Surgeons in the Confederate States Army By: J. Julian Chisolm, M.D.

- Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science By: Shauna Devine

- Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs By: Guy R. Hasegawa

- Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South By: Brian Craig Miller

- Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion By: Joseph K. Barnes, Joseph Janvier Woodward, Charles Smart, George A. Otis, and D. L. Huntington