Photography, a relatively new innovation, emerged as a burgeoning field during the Civil War. Learn more about how photography came of age during America's bloodiest conflict through these ten facts.

Fact #1: The Civil War was the first major conflict to be extensively documented through photography.

Although photographs of soldiers in the Mexican-American War (1846-48) and of battlefields of the Crimean War (1853-56) exist, neither of these conflicts were photographed to the extent of that of the Civil War. Not even close. Photographers visited camps, prisons, hospitals, and cities and captured thousands of photos on glass or iron plates. Some followed the Union Armies and recorded photos in real time and the field of photojournalism emerged. Northern audiences were both horrified and captivated by images of the war and clamored for more.

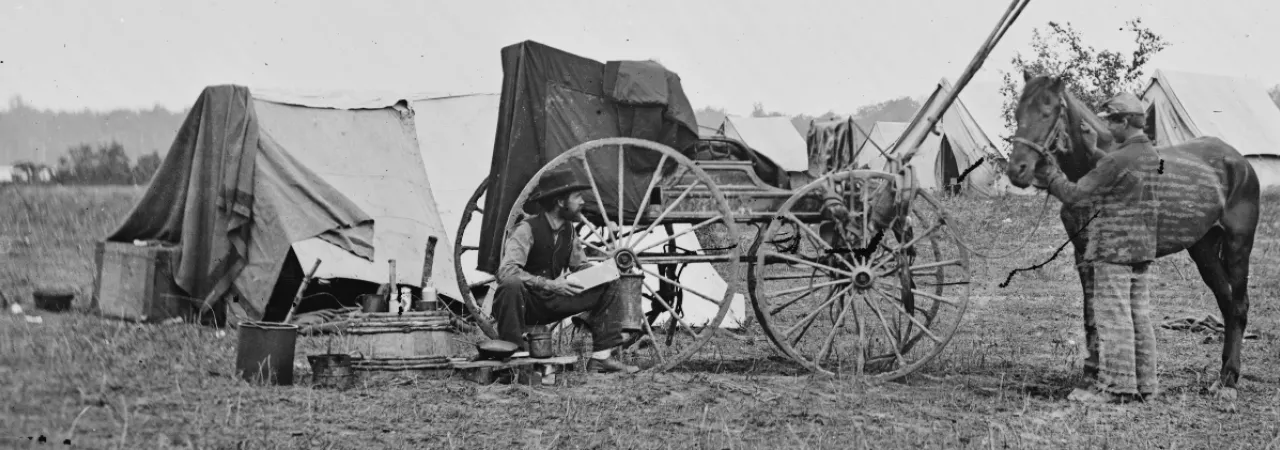

Fact #2: Taking photographs away from a studio was difficult and time-consuming.

Even in a studio, taking photographs was a complicated process. In order to take photographs away from their studio, photographers had to bring all the essentials from their studio out to the field, usually via wagons. This included the darkroom, a cramped space from which the photographer worked with dangerous chemicals to prepare and develop images. Cameras and lenses themselves were also heavy, bulky, and difficult to maneuver; positioning and focusing the camera was a process in itself. And all this was being done far from a base with a finite number of glass or iron plates and chemicals needed to make photographs.

Fact #3: Southern photographers took the first documentary photos of the war, but most Civil War images were made by Northern photographers of Eastern Theater subjects.

Within hours after Old Glory had been lowered over Fort Sumter, Southern photographers extensively photographed the aftermath of the bombardment. However, Southern photographs would become less and less common. Due to the tightening Union blockade, the South ran low on chemicals needed for photography. As a result, the overwhelming majority of Civil War documentary photographs were taken by Northern photographers, who had a seemingly endless supply of the materials they needed for their craft. Yet even they were limited by geography. Because the battles in the Eastern Theater were concentrated in a relatively small area, photographers were able to follow the armies and quickly move from site to site. But in the West, this was much more difficult, as battles there were separated by vast distances, which also limited the availability of photography chemicals. This imbalance leaves us with a dearth of photos of Confederates and westerners in the field.

Fact #4: The wet-plate photographic process allowed for the inifinte reproduction of an image through prints or artistic engravings.

The first iteration of practical photography and the predecessor to the wet-plate technique was the Daguerreotype. Named for its inventor Louis Daguerre, this process used a copper plate coated with silver iodide, which was exposed to light in a camera, fumed with mercury vapor, and made permanent with a solution of common salt. However, these complicated steps only yielded a single, unique image. The wet-plate process, in contrast, yielded negatives – which could be printed by placing a negative against light-sensitive paper in sunlight. An artist could also take a print – or even a negative – and make an engraving or “woodcut” which could then be mass-printed in newspapers, such as Harpers Weekly, allowing many Americans to see photographs in this form. The glass plate negative itself, when framed against a dark background, often velvet, turned “positive” to the eye and was called an ambrotype.

Fact #5: There were millions of Civil War portraits made, but only 10,000 documentary photographs were taken during the Civil War.

Civil War soldiers and civilians alike enjoyed having their portrait (or many!) taken. Some new recruits secured portraits before they left for the war, at local photography studios. During the war, portrait photography continued to be quite popular among the men, and soon armies had their own official civilian photographers assigned or allowed in camp. Common soldiers usually got their likeness in the form of ambrotypes or tintypes, as they were more affordable.

Fact #6: Wet-plate negatives produced a higher resolution than modern cameras.

The negatives produced by the wet-plate process were usually about four inches by ten inches in size but could be even larger. This makes them 20-30 times larger than negatives produced by a 35mm camera, thus having a much higher resolution. Furthermore, unlike 35mm negatives or even modern digital images which have grain or pixels, Civil War photos were fixed on chemical sheets, which had neither. As a result, we can zoom into these negatives and notice tiny details that the photographer himself may have never noticed. These details – that inform material culture, battlefield appearance, and more – add an incredible depth of humanity to the study of the Civil War.

Fact #7: Photographers photographed dead soldiers where they fell on nine occasions.

Some of the most striking Civil War photos are those that depict dead soldiers. However, these photographs only make up a small fraction of Civil War documentary photos. Roughly 103 photos of dead soldiers were taken during the course of the war, and only at the battlefields of Corinth, Antietam, Fredericksburg (twice), Gettysburg, Spotsylvania, Petersburg, and one yet to be determined location. Alexander Gardner’s 20 photos of dead soldiers at Antietam changed the perception of Civil War – and warfare in general – as civilians’ romantic notions of war were upended by inglorious, grotesque images of young men laying face-down in the dirt.

Fact #8: Nineteenth century 3D photos - or stereoviews - were popular during and after the Civil War.

Almost 70 percent of photographs taken during the Civil War were stereoviews, which were essentially 19th century three-dimensional photos. To take a stereoview, a photographer used a twin lens camera with its lenses an eye-width apart to capture the same image from slightly different angles, much as our own eyes do. Once developed and mounted on a card, these two photos were placed in a viewer, which created the effect of seeing these pictures in 3D, creating a unique, immersive experience for soldiers and civilians alike.

Fact #9: Combat photography was born during the Civil War.

As previously mentioned, the process of taking photographs in the 1860s was a complicated one. A photographer needed time and space to get his photos developed – and that could not usually be done safely during a battle, to say nothing of the danger and long exposure times that rendered photos of moving objects very difficult. However, photos of this nature do exist. For example, Northern and Southern photographers both captured images of ironclad ships shooting in Charleston Harbor in 1863 (which was the first ever photograph of actual combat), as well as others showing battle smock and even blurred troop movements during Second Fredericksburg.

Fact #10: Glass plates of famous Civil War images did not just burn away in the nation's greenhouses.

Most Civil War photographers created sales catalogs and we know which documentary negatives were made available for sale. Almost all of these negatives are held by the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and the Smithsonian. While some portraits – mostly failed or unclaimed by buyers – are known to have been used as greenhouse glass, the idea that the famed photos of the Civil War were burned away is myth.

Bonus Facts:

- Exposing a plate usually took several seconds, meaning the subject would have to be still for two to ten seconds.

- Tintypes were actually made on thin iron plates, which were so thin that they resembled tin. Hence the name tintype.

- Photojournalism, or documentary photography, first emerged as a field during the Peninsula Campaign in 1862.

- Photography had an important impact on the homefront and on civilians' perception of the war.

- Some of the photos attributed to Mathew Brady were taken by his numerous assistants.

- Yes, some people smiled in Civil War photos!