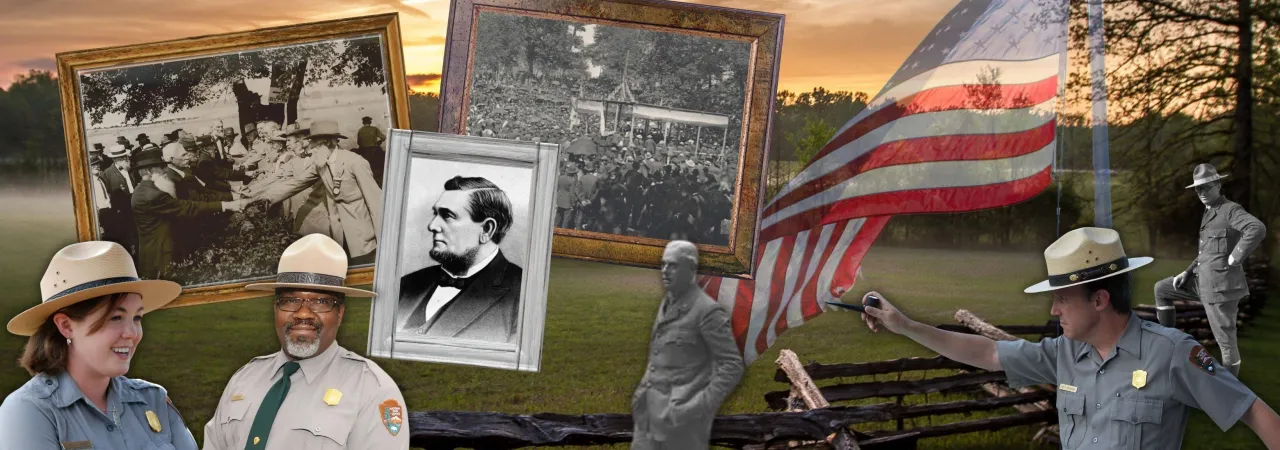

10 Facts: The Birth of National Battlefield Parks

Since the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, by President Woodrow Wilson, the public has gained valuable access to and information from treasured American landscapes. But the National Park System does so much more than simply preserve the natural landscape — it also protects places critical to American history. Today, of the 423 units of the National Park Service, there are four national battlefield parks, nine national military parks, 11 national battlefields, one national battlefield site and several more national historical parks and national monuments dedicated to telling the United States’ dynamic military history. And even before the establishment of the National Park Service, many battlefield sites had vital support from the federal government.

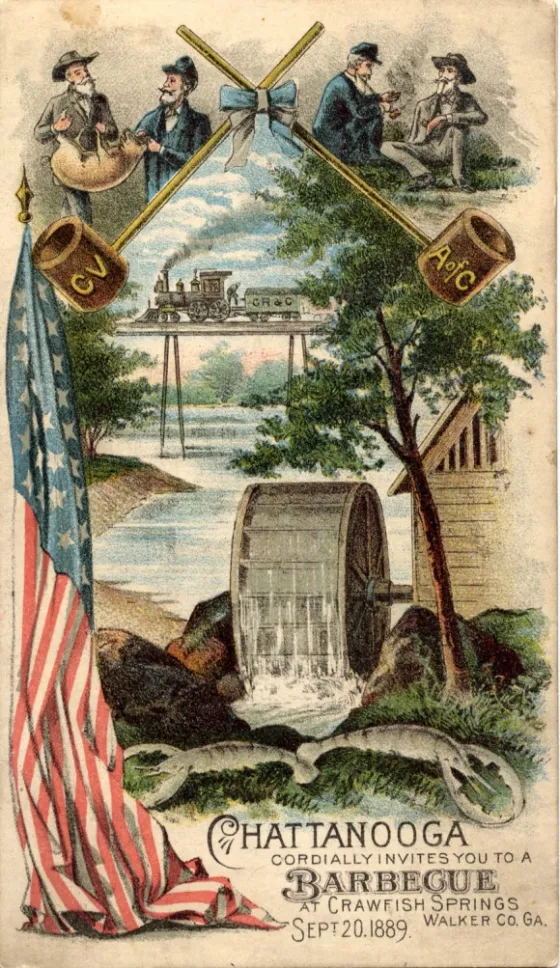

Fact #1: A BBQ inspired the creation of the first national battlefield park at Chickamauga and Chattanooga.

In 1889, roughly 14,000 Union and Confederate veterans returned as reunited countrymen to the Chickamauga Battlefield for the Blue and Grey BBQ, arguably one of the greatest barbeques in U.S. history. With the presence of patriotism and a desire for commemoration, the gathering served as an influence to demonstrate that hallowed ground could be used as a means for unifying, remembering and healing from conflicts of years past.

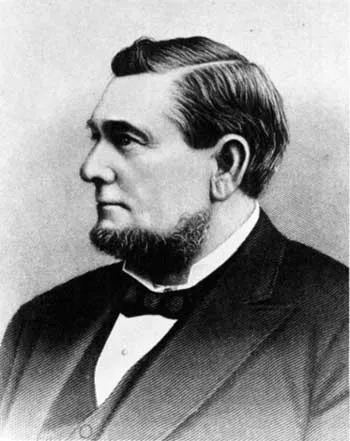

Inspired by veterans memorializing the battlefield landscape at Gettysburg, Union veterans Gen. Henry V. Boynton and Gen. Ferdinand Van Derveer envisioned the Chickamauga and the Chattanooga Battlefields as "a Western Gettysburg.” A proposal was concocted and went on to receive support from every level of power until the House Military Affairs Committee. The committee created a report detailing the history of the battles, integral sites and the creation of observation towers. The report quickly transformed into a bill that ultimately landed on President Benjamin Harrison’s desk. On August 19, 1889, the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park was born.

Tune in to this video from the Trust’s visit to Crawfish Springs to learn more about the famous BBQ!

Fact #2: The Gettysburg National Cemetery came before the Gettysburg National Military Park.

Because of the mass amounts of casualties from the three-day battle, Pennsylvania Gov. Andrew G. Curtin quickly approved plans for a cemetery to honor those fallen and buried on the battlefield. The cemetery was designed by William Saunders, the Scottish-born superintendent of the Department of Agriculture. Saunders wanted the cemetery to appear in the simple grandeur style, which emphasized simplicity. The cemetery was dedicated on November 19, 1863, but would forever be preserved in history as the site of Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address.

In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant authorized the transfer of the Gettysburg and Antietam Cemeteries into federal hands. That same year, Grant established the first national park at Yellowstone. Gettysburg National Military Park was established in 1895.

Fact #3: National battlefield parks were first governed by the War Department.

Influenced by the work of Civil War veterans, the government stepped into the world of battlefield preservation in its modern sense in 1890, rooted in the creation of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. The National Park Service had yet to come into existence and only a few other federal parks were in operation, including Yellowstone, Yosemite and Sequoia. Federal battlefield parks at Antietam, Shiloh, Gettysburg and Vicksburg also came to be in the 1890s. With the War Department in charge of these fields, they often took on a very militaristic atmosphere for veterans and military officers studying the lessons of war.

Some view this initial period to be the “golden age” of preservation, when veterans exerted great power in preserving and memorializing these hallowed landscapes on a sweeping scale. Today, these first five federally associated battlefields function as some of the best-preserved and marked Civil War sites that visitors can witness.

Fact #4: In the initial years of national battlefield parks, veterans and military were the primary visitors.

With the first slew of national battlefields brought to life through the efforts of veterans, it is no surprise that many revisited the sites that molded their Civil War military experience. This hallowed ground carries haunting memories and lessons learned through the most trying of circumstances. Influenced by the guidance of the War Department, these sacred spaces were naturally shaped by military of the past and present.

In 1896, Congress passed a measure that allowed for all national battlefield parks to be “fields of military maneuvers for the Regular Army of the United States and the National Guard of the States.” To this day, military students learn battlefield history at these sites because of this legislation – the Trust even provides assistance with staff rides!

- Fun bonus fact: In 1924, roughly 3,200 Marines marched from Quantico, Va., to the Antietam National Battlefield, where they spent 11 days conducting field exercises, and were accompanied by all the equipment that would be needed for a major deployment, including tanks, aircraft, balloons, machine guns, artillery and trucks. They also held baseball games, concerts, parades, ceremonies and dances.

Fact #5: “The Antietam Plan” became the model for all national battlefields and military parks from 1902 to 1933.

Originally created by Brig. Gen. George Breckenridge Davis, the “Antietam Plan” urged the federal government to only buy small plots of land where battles lines were drawn. At the Antietam Battlefield, Davis believed that the agricultural core of the 1862 battlefield should remain intact, and that preservation should work around it:

"If it is the purpose of Congress to perpetuate this field in the condition in which it was when the battle was fought, it should undertake to perpetuate an agricultural community.... That was its condition in 1862, and that is the condition in which it should be preserved."

This plan was used in the preservation of battlefields like Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Chancellorsville and the Wilderness. It remained the main preservation plan until the battlefields were transferred to the Department of the Interior’s National Park Service.

Fact #6: The transfer of battlefield parks to the National Park Service (NPS) did not occur until 1933.

NPS Director Stephen Mather and his assistant, Horace Albright, had long argued for the change, explaining that the National Park Service, established in 1916 by President Woodrow Wilson, was the government agency that had expertise in park management and interpretation.

When the pair visited Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park in 1915, when it was under the direction of the War Department, Albright noted, “Since the park boundaries were not well marked, I was never sure when I was in the park, except where historic site markers had been installed. I met no park employees.” And at Gettysburg in 1926, Albright remarked, “We were astonished at the small acreage of these lands, not an acre of the first day’s battle being owned by the War Department. We were also unhappy about the quality of the guide service.”

As battlefield visitors were no longer made up primarily of veterans or military officers, a new kind of experience had to be sought to bring the more mobile civilian American public to the battlefields — an experience that could be provided by the National Park Service. In the summer of 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6166, transferring 10 major battlefields and numerous other smaller sites to the National Park Service.

Fact #7: Guilford Courthouse National Military Park was made possible due to the efforts of ONE man.

As seen through the early efforts at Chickamauga & Chattanooga and Gettysburg, the collective efforts of determined individuals kickstarted battlefield preservation in the late 1800s. But not all individuals involved in these efforts were veterans looking to save the hallowed ground where their brothers in uniform fell. The Guilford Courthouse Battlefield, an unindustrialized rural landscape, was largely forgotten by nearby North Carolina residents by the 1880s — but not by Judge David Schenck!

With hopes “to redeem the battlefield from oblivion,” Schenck purchased part of the battlefield and convinced others to join in, establishing the Guilford Battleground Company. By beautifying and ornamenting the battlefield landscape, the company drew public attention and support for its further preservation.

In March 1917, legislation established the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park under the War Department. It was later transferred to the National Park Service in 1933.

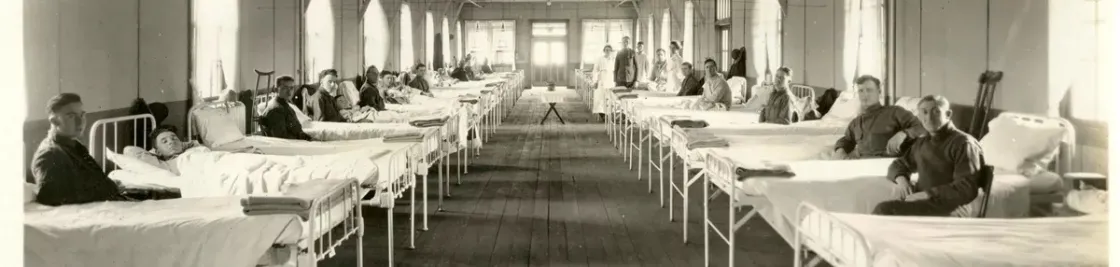

Fact #8: Before it became a National Park Service site, Fort McHenry’s wartime purview expanded to World War I.

Despite its structures and defenses being too outdated for modern wartime machinery, Fort McHenry became a pivotal site when the United States entered World War I. The fort’s grounds were transformed into a massive 100-building and 3,000-bed hospital, called General Hospital No. 2, in use from 1917 to 1925.

After the hospital’s closure, the U.S. Army began the process of restoring the fort to its mid-1800s appearance. And when “The Star-Spangled Banner” became the National Anthem of the United States, the site’s importance skyrocketed. By 1933, it was transferred to the National Park Service as Fort McHenry National Park. But by 1939, the site took on a new title — Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. The Second World War called the fort back into service as a training facility for the U.S. Coast Guard, but it was returned back to NPS by 1945. Of the 423 NPS units, it is the only one to carry the designation of “Historic Shrine.”

Fact #9: Originally Virginia’s first state park, Richmond Battlefield became the 17th unit of the National Park System in 1936.

After the Richmond Battlefield Parks Corporation deeded all its property to the Commonwealth of Virginia on January 12, 1932, the Richmond Battlefield State Park became Virginia’s first state park. But by 1934, Virginia realized that it didn’t have the necessary funding to build and maintain the park, which consisted of parcels that were miles apart and highlighted a variety of Richmond battle sites. The Commonwealth soon began to seek out the park’s transfer to the National Park Service. On March 2, 1936, an act of Congress established the Richmond National Battlefield Park as part of the National Park System.

Fact #10: The American Battlefield Trust maintains a close relationship with the National Park Service.

To date (April 2022), the Trust has transferred approximately 4,935 acres to NPS! The National Park Service, in turn, manages the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) — the source of federal matching grants that enable the Trust to leverage member donations for acquisition, interpretation and restoration projects. It also maintains the official rosters of the principal battles and their geographic footprints — plus the authoritative list of conflicts with their dates and belligerents across American history. On many fronts, the Trust’s work would not be feasible without ABPP.

Aside from acquisition, interpretation and restoration projects, the Trust has also collaborated with NPS to establish a 5-year partnership to bring intensive leadership and character-building experiences to youth organizations and at-risk students through the “Great Task” Youth Leadership Program at Gettysburg. Other collaborative activities include Trust advocacy to keep land adjacent to national battlefields free of 21st-century infrastructure, NPS guest appearances on Trust video productions and much more.