Midshipmen 4th Class, or plebes, during the third week of Plebe Summer, a demanding six-week indoctrination period intended to transition the candidates from civilian to military life.

As part of a series on military service academies, Dwight Hughes, Class of 1967, covers the history of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md.

“The training which Naval [Academy] Cadets receive is admirable, and the education makes them useful citizens, and strengthens the defense of the country,” wrote James I. Waddell, who had served in both the United States and Confederate States navies, in his 1885 memoir. However, he continued, “The all important, useful and necessary branches of my profession, I learned at sea, on ship board, while a boy…. I may be in error when I assert that practical seamanship cannot be learned from books….”

In this sentiment, Waddell personified the antebellum evolution from the ancient school of the sea to professional naval officer education. He first went to sea as a traditional midshipman of the old wood-and-canvas navy at age 16 in 1841. Six years later, he reported to the new school at Annapolis, where he and other seasoned mariners studied uncomfortably alongside youngsters fresh from civilian life to be certified as passed midshipmen.

Cruising the globe for the next decade, Waddell advanced to lieutenant and served a tour teaching navigation at the Academy. In 1861, the North Carolinian was second in command of the USS Saginaw, a brand-new steam sloop of war on the China Station, when he swapped blue for gray, ultimately commanding the infamous Rebel commerce raider CSS Shenandoah.

Waddell had become an officer the hard way and, to him, the right way: a slow, tedious progression through the ranks based on seniority, which gave enormous prestige to promotion. He doubted the practical application of classroom learning and seemed to harbor resentment for book learners. Such controversies had delayed the launch of a naval academy for 40 years after West Point’s founding and underscored the tension between academic learning and professional training.

Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft established the Naval School at the former Fort Severn in Annapolis, Maryland, on October 10, 1845, with a class of 50 midshipmen and seven professors. The initial curriculum involved two years of study in mathematics, navigation, gunnery, steam engineering, chemistry, English, natural philosophy and French. This was to be followed by three years’ service afloat, and another year at the school before sitting for the lieutenant’s exam. Five years later, the Naval School became the Naval Academy, with a full four-year course of study augmented by summer training at sea.

In his history of the antebellum Academy, The Spirited Years, Charles Todorich concluded: “It was during this [antebellum] period that the efficacy of formal naval education was proven….” The new commandant of midshipmen established authority over daily affairs and, with the Executive Department as police force, maintained firm discipline over unruly young men. The broad-based, college-like curriculum taught by civilian professors transmuted midshipmen from quasi-officers to student-cadets. A mutually beneficial relationship developed with the city of Annapolis. The Academy soon became the near-sole supplier of officers to the fleet and a repository for navy memorabilia and tradition.

Despite periods of stagnation and neglect, the sea service had come a long way since its baptism by fire during the undeclared war with France in 1798. By mid-century, a more efficient departmental structure replaced the ad-hoc administration of the past. A body of trained sailors manned the fleet; flogging had been outlawed and alcohol would be banned afloat (for the Union navy) in 1862. Six new screw-driven steam frigates, a class of smaller steam sloops of war and innovations in naval artillery initiated a technological revolution and rebuilding that would accelerate dramatically during the coming conflict.

However, nothing in the history and traditions of the United States Navy prepared it for civil war. U.S. warships were still cruising individually or in small, semipermanent squadrons on far-flung stations to show the flag and to protect the burgeoning, global American shipping and whaling industries. The navy of 1860 trained primarily to refight the War of 1812 — glorious single-ship duels against a foreign foe, and commerce warfare with pirate suppression as needed. Massive Civil War campaigns with elements like a continent-wide blockade, reduction of shore fortifications in heavily defended ports, amphibious assaults, coastal and riverine warfare and coordinated army-navy operations were not imagined.

A small but formidable officer corps served with proud heritage and expert seamanship. Their heroes were intrepid and pugnacious captains: John Paul Jones, Thomas Truxton, Edward Preble, David Porter, William Bainbridge, Isaac Hull and Stephen Decatur commanding ships like the Enterprise, Essex, Philadelphia, Constellation and Constitution. They drew inspiration from Jones proclaiming, “I have not yet begun to fight!” in his 1779 victory over the HMS Serapis and Capt. James Lawrence gasping, “Don’t give up the ship!” as he lay dying on the bloody deck of the USS Chesapeake following defeat by the HMS Shannon in 1813.

But with no standards for selecting and educating officers or for weeding out the physically and mentally unfit, that hard-won professionalism was not universal or consistent. Alcoholism and disciplinary infractions afloat were prevalent, leading to numerous courts martial, and dueling was quite common. During a training cruise to the West Indies in 1842, Midshipman Philip Spencer, the son of the secretary of war, was hanged for attempted mutiny. Salty old captains and commodores clogged the promotion pipeline, while talented but frustrated lieutenants and midshipmen groused, and many left the service.

Midshipmen appointments had been the prerogative of ship captains, the secretary of the navy and the president, with political and personal influence being the highest criterion. “A cruise in Washington” went a common adage, was “worth two around Cape Horn.” Such lobbying undercut the secretary’s authority and further undermined discipline. Well-connected applicants who could read and write and possessed the basics of arithmetic and geography were acceptable. One navy secretary referred to “wayward and incorrigible boys, whom even parental authority cannot control.”

Sporadic efforts to educate midshipmen at navy yard schools and with shipboard civilian instructors were ineffective. A lucky young man might receive rudimentary instruction in mathematics, navigation and languages, but many received no formal instruction. Boys like James Waddell were treated as servants, their progress hostage to a captain’s often lagging interest. Afloat, they learned by doing under the strict discipline of lieutenants and the tutelage of grizzled senior seamen. “The whole system of naval education in those days was rough and crude, and did not seem altogether fair; the wonder is that we got on as well as we did,” recorded retired admiral Samuel Franklin late in the century.

Mariners were generalists in the millennia-old technology of sail, employing muscle and simple tools to maneuver huge, complex machines through all Neptune’s moods. A ship heeled to the wind, they sustained a tenuous equilibrium with the elements in a masterful choreography of sea and sky, often with uncertain progress. Their open-air attention was always upward and outward. Sailors’ skills were not amenable to book learning — more art, instinct and experience than science or technical understanding.

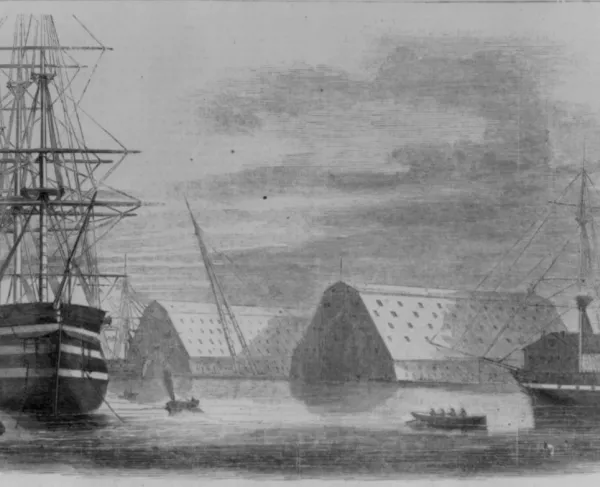

In a few decades, however, the expertise required to manage a tall square-rigger would become archaic and nearly superfluous. Internal propulsion — less than a half-century old and rapidly developing — placed potent propulsive power in human hands, channeling it into purposeful motion frequently in opposition to the elements. In reasonable conditions, a ship sits up and goes where she is pointed.

The new profession of marine engineer foreshadowed the machine age. Denizens of engine and boiler spaces — claustrophobic dens of darkness and fire, intense heat and noise, reeking of iron, oil, coal and sweat — were specialists who shared little in the way of knowledge or sensibilities with those above. They focused inward. There could hardly be a greater disparity in concept and feel, a manifestation of increasing human dominance of creation.

Sea officers were not accustomed to being dependent on technicians whose equipment they only generally understood. The old guard respected the potential of steam and iron but insisted on conservative and practical evolution. In this transitional process, the new technology had not yet proven its efficacy against the nation’s enemies while preserving her sons, although the coming of war would markedly accelerate the pace of proof. A dedicated cadre of exasperated younger officers was anxious to learn and adapt, but also was not being educated like West Point and university counterparts, which diminished both professional and social status.

As far back as 1777, Capt. John Paul Jones, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson proposed formal naval officer education. Secretary of the Navy William Jones urged Congress to establish an academy in 1814 for instruction in mathematics, “experimental philosophy,” the “science and practice of gunnery, theory of naval architecture, and art of mechanical drawing.” He failed, as did nine subsequent secretaries. In 1825, President John Quincy Adams urged Congress to establish a naval academy “for the formation of scientific and accomplished officers.” Secretary of the Navy Samuel Southard, in 1827, appealed to efficiency, economy and national honor: “The American naval officer is, in fact, the representative of his country in every port to which he goes, and by him that country in a greater or less degree estimated.”

But, with the nation facing no immediate external threat, Congress and the public were not interested. A professional naval officer corps violated Jacksonian populism; it smacked of aristocracy and the Royal Navy. Americans gazed westward, where the army facilitated settlement while the navy was out of sight, out of mind. And it was expensive. Senior officers feared that book learning, culture and refinement would emasculate young officers, diluting the hero spirit.

Meanwhile however, self-educated mid-grade officers facilitated an explosion in global discovery and science driven by the new nation’s burgeoning trade and influence, its demands to exploit rich trade routes and destinations and the need to protect those who went there — a maritime Manifest Destiny. Matthew F. Maury, the “Father of Oceanography”; ordinance experts John A. Dahlgren and John M. Brooke; and explorers Charles Wilkes and John Rodgers gained international renown. They also demanded reform: “Never before has the spirit of discontent, among all grades in the Navy, walked forth in the broad light of day, with half such restive but determined steps,” wrote Lieutenant Maury in 1840. These men would lead on both sides in the coming conflict.

The impetus for an academy gained steam. The great revolution in naval technology demanded technically competent officers. Between 1843 and 1860, the number of sailing warships decreased from 59 to 44, while steamers increased from 6 to 38. Meanwhile, war with Mexico loomed and tensions with Great Britain flared.

Three committed men established the Naval Academy. First, Navy Secretary George Bancroft — distinguished educator, politician, historian and statesman — constituted federal authority. Renowned mathematician William A. Chauvenet contributed academic credibility and prestige with a curriculum that resembled West Point’s and covered mathematics, navigation, astronomy, surveying, steam mechanics, drawing, gunnery, foreign languages, history and maritime law. As first superintendent of midshipmen, Cdr. (and future Confederate admiral) Franklin Buchanan brought ashore 30 years on the salt and strict naval discipline.

A decade of growing pains followed, but by 1861, the institution rivaled the school on the Hudson in professional quality and prestige. And like the Military Academy on a lesser scale, the Naval Academy provided core talent to both sides in the Civil War, its instructors as more senior officers and graduates among middle and lower ranks. The second superintendent, Cdr. Sidney Smith Lee (brother of Robert E. Lee) became a senior Confederate navy captain.

Among many lieutenants, William H. Parker, class of 1848, established an impressive combat record and the Confederate States Naval Academy. Charles Read, “anchor man” (graduated last) in the class of 1860, caused panic in New England with an attack on the harbor of Portland, Maine. Lt. (and future admiral of the navy) George Dewey, class of 1858, steered the USS Mississippi past the blazing guns of forts at New Orleans.

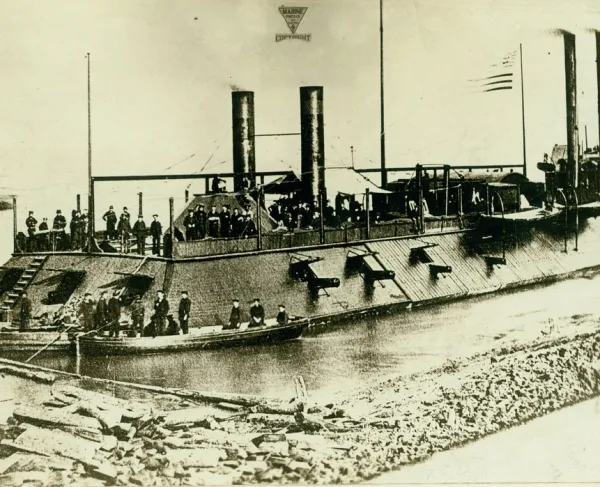

Samuel D. Greene, class of 1859, captained the USS Monitor against Franklin Buchanan commanding the CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack). William B. Cushing was expelled just before graduation in 1861 for pranks and poor scholarship but reinstated as war came. Among other feats, he famously sank the Rebel ironclad Albemarle with a small boat and a spar torpedo.

Ultimately, 400 graduates served in the Union navy and 95 in the Confederate navy. Twenty-three graduates were killed in battle or died of wounds. A new generation was educated at the United States Naval Academy, steeped in new technology, and fired in the crucible of war to lead the sea service into the 20th century.