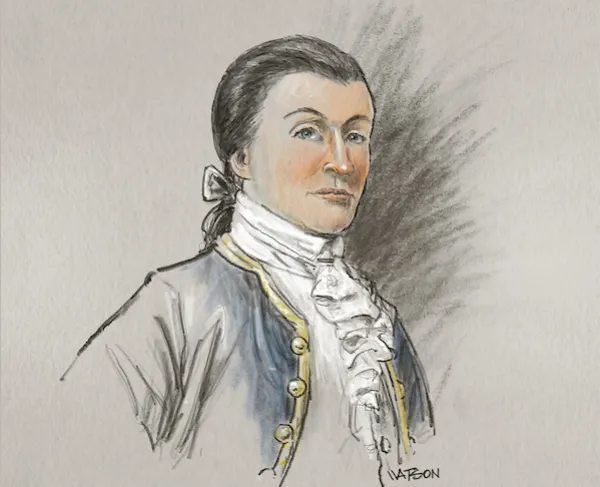

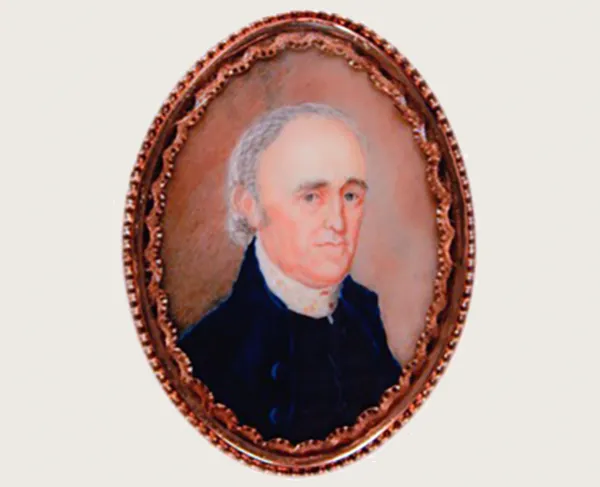

Henry Clinton

Born in Newfoundland in 1730, Henry Clinton was the son of George Clinton, an admiral in the British Navy and the governor of Newfoundland. George received a post as governor of New York in 1741 and when he departed for the colonies in 1743, Henry accompanied his father. At the age of fifteen, Henry took his first military commission in the New York militia. One year later, his father’s connections secured him a captain’s commission and, in 1749, he left the colonies for Britain to further his military career.

Henry first saw action during the Seven Years’ War. He began as a captain in the Coldstream Guards in the early 1750s and eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the 1st Foot Guards. In 1762, he received a post in Germany and became the aide-de-camp to Prince Ferdinand. In 1772, Henry achieved two major feats for a person of colonial birth: a seat in Parliament and a major generalship. Much of his initial success and the titles he acquired were due to his father’s close friendship with the Duke of Newcastle.

On his way to Boston with William Howe and John Burgoyne to reinforce the British position, Clinton first learned of the outbreak of the Revolution. Once in Boston, Clinton and the other British generals worked to reinforce the city and break the siege. Clinton rallied troops and sent reinforcements to attack the Continental Army’s position during the Battle of Bunker Hill and helped secure a British victory. In 1776, he accompanied a failed British mission to capture Charleston and offset that loss with two successful campaigns in New York and Long Island. His victories earned him the rank of lieutenant general.

For the 1777 campaign season, the British planned a two-pronged assault: one army targeted Philadelphia and the other descended south from Montreal to Albany, New York. Their goal was to deal the Continental Army a fatal blow by dividing the colonies in half. King George III bypassed Clinton in favor of Burgoyne for command of the northern campaign. Clinton protested this perceived slight by trying to resign. The King refused and ordered him back to New York but offered Clinton a knighthood to appease him. Ultimately, the northern campaign ended terribly for the British when Burgoyne surrendered a large force at Saratoga.

After a disastrous year, Clinton replaced General Howe as Commander-in-Chief of North America. Looking to capitalize on some of the success the British experienced the previous year, particularly at Savannah, Georgia, Clinton turned his attention to the Southern Colonies. Many believed that latent Loyalists resided in the southern backcountry and would rally around the British upon an invasion. In 1780, Clinton initiated a siege of Charleston, South Carolina and eventually forced the surrender of the city. This marked a major British victory and sparked a campaign to secure South Carolina. From his headquarters in New York, Clinton maintained active communication with Cornwallis, the commander of the southern army. Clinton was well aware of the challenges faced by the British during the Southern Campaign. Sensing Cornwallis’s doom in the fall of 1781, Clinton attempted to reinforce him at Yorktown, but he was too late. Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown on October 19, 1781.

Despite Cornwallis’s prominent role in the loss and surrender, Clinton, as Commander-in-Chief, was blamed for the loss of the American colonies. After the Revolution, he published a narrative account of the war in an attempt to clear his name. By 1793, Clinton became a full general and received an assignment as Governor of Gibraltar. He died before he could assume the post.

Related Battles

5,506

258