Rose O'Neal Greenhow

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was born into obscurity, but became one of the most powerful women in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately for the Federal government, she was a “Southern woman” and a Confederate spy.

Between 1813 and 1814, Rose was born on a small farm in rural Montgomery County, Maryland. Instead of her birthname “Maria Rosetta,” she went by the name “Rose” and continued to do so for the rest of her life. At the age of thirteen or fourteen, she moved to Washington, D.C. Once there, Rose became fascinated with the Washington socialite scene and attempted to gain acceptance by the well-to-do Washingtonians. Even though she was mocked for her low birth, she eventually caught the eye of Dr. Robert Greenhow, a federal librarian and translator with medical and law degrees. The couple married on May 26, 1835 and, with her new husband, Rose gained acceptance into high society and socialized with famous Washingtonians, like First Lady Dolley Madison.

Robert, who was working for the Federal government, was transferred to the West Coast in 1850. Rose followed with the couple’s three children. However, after several years Rose returned to Washington, D.C. to give birth to her fourth child. Robert was supposed to follow within the year, but fell from an elevated sidewalk in California and succumbed to internal injuries on March 27, 1854.

Now widowed and fueled with a pension from the Federal government, she bought a house four blocks north of the White House and resumed her socialite occupation. She maintained political alliance with Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans and her influence was used to help James Buchanan get elected president in 1856.

However, she prided herself on being a “Southern Woman” and when the Civil War broke out, she aligned herself with the Confederacy. In Spring 1861, she became a Confederate Spy. Through Henry Wilson, a chairperson on the Senate Military Affairs Committee, Rose heard that the Union Army was consolidating their forces and planned to advance on Manassas, Virginia. Rose drafted Bettie Duvall, a young Confederate-minded woman, to help her warn the Confederate troops. Rose wrote a cipher and hid the note in Duvall’s hair. Duvall then snuck out of Washington dressed as a lowly farmer woman and made her way to Confederate-occupied Fairfax Court House, Virginia. While first wary, the Confederate commanders eventually allowed her an audience. To the officer’s amazement, she unraveled her hair to reveal and revealed the secret message. With this information, the Confederate Army was able to consolidate their forces and prepare for the Federal attack. This engagement, which became known as the First Battle of Manassas, was a Confederate victory.

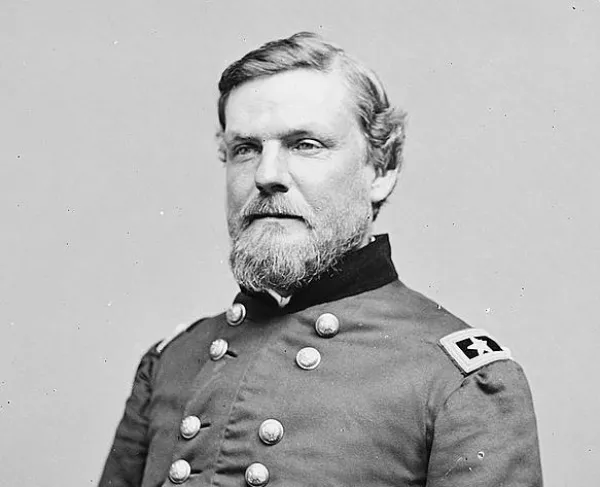

Greenhow’s spy network spanned several states and included 48 woman and two men. These conspirators included her dentist, Aaron Van Camp, and the prominent D.C. banker William Smithson. The network used a sophisticated cipher to code and decode messages. She sent at least eight ciphers to General P. G. T. Beauregard regarding Union fortifications around Washington, D.C. Beauregard hoped to attack, and then capture, the Northern capital city. However, his plan was eventually labelled impractical and he was transferred to Tennessee when he started conflicts with other Confederate officers. Rose continued her espionage work for other Confederates in the area.

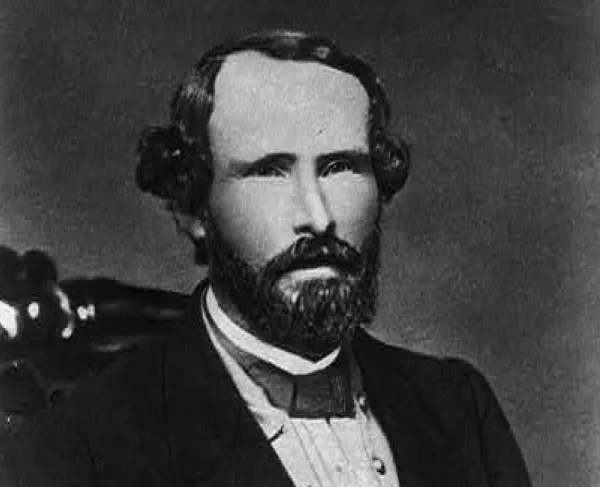

Rose, while brilliant at collecting information, was careless about storing information. She kept copies of messages sent to Beauregard in coded and decoded form, maps of the Union fortifications, and other incriminating documentation in her home. She eventually caught the attention of Thomas A. Scott, an assistant secretary of war, after he received an anonymous tip that Rose was a Confederate spy. Scott assigned Allan Pinkerton, head of the recently formed Union Intelligence Service and the founder of America’s first detective agency in Chicago, to monitor Rose.

On August 22, 1861, Pinkerton cased Greenhow’s house and noticed a young Union officer entering. Standing on the shoulders of a fellow officer, he spied into the front parlor and noticed the officer and Greenhow speaking in hushed tones and looking over a map of Union fortifications. Pinkerton waited until the officer left the residence and tried to flag him down. When the officer ran, Pinkerton followed. Unfortunately, the officer ran to the provost-marshal station and had Union soldiers arrest Pinkerton. He was thrown into a holding cell in a nearby guardhouse. By bribing a guard, Pinkerton was able to send a message to Scott about what he just witnessed. Scott summoned Pinkerton to the War Department and, after confirming his story, arrested the officer immediately.

The War Department then went after Rose. As she was returning from a walk the next day, Rose was approached by Union soldiers and arrested. The soldiers then searched her house. The map of Union fortifications that the officer showed her yesterday was found with other incriminating materials and Rose was placed under house arrest with her youngest daughter “Little” Rose. Other raids of Confederate-sympathizers and spies were conducted in DC in the following weeks and suspected spies, like Rose’s friend Eugenia Phillips, were imprisoned in Rose’s home. The house became known as “Fort Greenhow.”

Rose’s espionage did not stop. When Phillips was able to convince her husband’s friend, and Federal Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton to allow her to return to the South, she worked with Rose to slip information to the Confederacy. In addition, Rose was able to communicate with members of her network via different colored handkerchiefs that she waved through the window and notes that were smuggled in and out of her house. She was able to sneak out a letter from her house to Secretary of State William Seward demanding she be released, which was also sent to the Confederacy and printed in a Richmond newspaper. Upset that she continued to pass information to the Confederacy, the War Department moved her to the Old Capitol Prison with her daughter on January 18, 1862. This change in scenery did not stop Rose from being a nuisance and was able to smuggle in a Confederate flag to her prison cell and wave it from the prison window.

Fearing that she could expose governmental secrets or make a mockery of government officials, Rose was not tried. She was released on May 31, 1862 and told not to leave Confederate borders. Hailed as a hero by the South, she was cared for by Richmond socialites and met Jefferson Davis. That summer she went against Federal orders and embarked on a diplomatic mission to France and Britain to garner support and funds. While there, she became engaged to Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl of Granville, and wrote her memoir My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington.

Carrying two thousand dollars’ worth of gold for the Confederacy, she headed back to America on August 19, 1864 aboard the Condor, a British blockade runner. On October 1st, as the Condor reached the mouth of Cape Fear River near Wilmington, North Carolina the captain thought he spotted Union ships. Attempting to escape the ships, the Condor became grounded. Greenhow and two other Confederate agents, worried about being captured, requested a rowboat from the captain and started paddling toward the shore. The rowboat capsized. Weighted down by the gold, Rose drowned. Her body was found several days later and was buried with full military honors by the Confederacy. After her death, she became a revered symbol for the Confederate Cause and left a legacy of Confederate espionage.