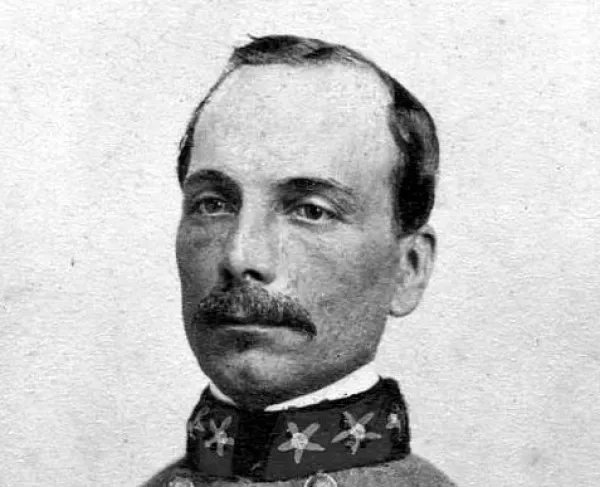

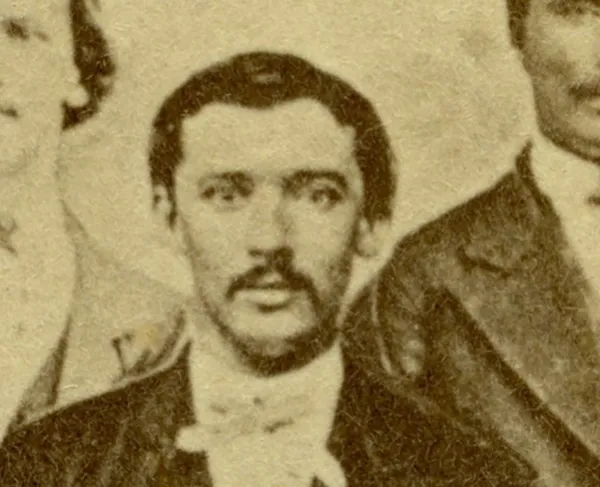

Pinckney Benton Stewart (P.B.S.) Pinchback

Pinckney Benton Stewart (P.B.S.) Pinchback dedicated his life to the Republican Party and improving African American status in the United States.

Pinchback was born to parents, Major William Pinchback, a white Mississippi planter, and Elize (or Eliza), Major Pinchback’s former slave, on May 10, 1837, in Macon, Georgia. The family was enroute to their new plantation in Holmes County, Mississippi. Pinchback was the eighth of ten children.

Pinchback learned to read and write. At age nine, he was sent to The Gilmore School in Cincinnati, Ohio, though his school days ended in 1848 after his father’s death. Because a Mississippi Court denied Elize the inheritance of Major Pinchback’s estate, young P.B.S. Pinchback became the financial support of his family, working a “cabin boy” on a canal boat and making $8 per month. His mother and siblings joined him in Ohio, fearing that white relatives would re-enslave them. In time, Pinchback became a Ship Steward, working on boats on the Mississippi, Ohio, Missouri, and Red Rivers. He married Nina Emily Hawthorne in 1860.

During the American Civil War, Pinchback ran the Confederate blockade on the Mississippi River to get to New Orleans, a city captured by Union forces in 1862. General Benjamin Butler tasked Pinchback with recruiting soldiers for a “Corps d’Afrique.” At the beginning of the Civil War, 18,000 free African Americans lived in New Orleans. Pinchback became the Captain of Company A in the Louisiana Native Guards 2nd Regiment, later known as the 74th U.S. Colored Infantry. The Unit, stationed at Fort Pike, maintained coastal defenses, and guarded prisoners. Pinchback resigned from his captaincy in September 1863, citing unequal pay as well as discrimination with promotions.

After experiencing discrimination and inequality in the Union Army, Pinchback sought reforms. The New-Orleans Times noted some of Pinchback’s public remarks,

He stated…that he or his fellow-citizens had no favors to ask of the United States Government; they only demanded as a right that they should be allowed the right of suffrage. They were fighting our battles, and were willing to fight them. They did not ask for social equality, and did not expect it, but they demanded political rights—they wanted to be men. He cared not for the past, but the future. He believed that if colored people were citizens they had a right to vote. If they were not citizens, they were exempted from the draft.

Pinchback dedicated years of his life to advocacy. He traveled to the Northern states to speak for voting rights. In 1865, he spent time in Alabama, helping free Black men campaign for political rights.

Pinchback returned to his family in New Orleans and influenced the local political scene. Following the passing of the Reconstruction Act, which removed former Confederates from power and protected Black rights, Pinchback founded the New Orleans’ Fourth Ward Republican Club. At the Louisiana Constitutional Convention in 1868, he penned an article enfranchising Black men. Pinchback also oversaw a Republican newspaper, the New Orleans Louisianan. That same year, following a contested election, Pinchback was sworn into the Louisiana State Senate. He introduced numerous bills and articles, including the establishment of Southern University, a Black college. Pinchback’s efforts to improve the status of African Americans angered Liberal Republicans and Democrats; a political dissenter attempted to assassinate Pinchback, but he survived.

In 1871 Pinchback’s political career accelerated. As President Pro Tempore of the Louisiana State Senate, Pinchback became Lieutenant-Governor when the incumbent died. Shortly thereafter, Republican Governor Henry Clay Warmoth was impeached by his fellow Republicans when he attempted to certify a largely contested election in favor of Democrats and Liberal Republicans (those who opposed Radical Reconstruction). With Warmoth suspended, Pinchback became the first African American governor in the United States. He was governor for only thirty-five days, due to the incoming government’s start of term; nevertheless, he passed ten laws. During this period, he received death threats from citizens of New Orleans and the Ku Klux Klan in other states.

After the new governor, William Pitt Kellogg, took office, Pinchback ran for Kellogg’s now vacant U.S. Senate seat. The election was contested, and the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections investigated, eventually determining that Pinchback would have won if the election had been fair but then forcing the seat to remain empty for three years. During the long debate over the Senate seat, Pinchback won an election to the House of Representatives. He refused to accept the House seat, waiting to be seated in the Senate. Twice, Pinchback had theoretically won government seats of office and was not seated for either. He did receive compensation for expenses and a salary during the debate around the senate seat, which became known as the “Louisiana Case.” In the end, a Democrat filled the empty Senate seat.

Pinchback maintained his politic work, repeatedly serving as a delegate at the National Republican Conventions. At age 50, he enrolled in Straight College as a law student, and he was admitted to the Bar. Pinchback relocated his family to New York and Washington D.C. in the 1890s, where he practiced law. He also chaired the national American Citizen’s Equal Rights Association.

Pinchback died after a lengthy illness in Washington, DC, at the age of eighty-four. His wife and grandson escorted his remains back to New Orleans, Louisiana, and he is interred at Metairie Cemetery. The New York Age eulogized Pinchback as “uncompromising in his assertion of personal independence and fearless of consequences in the expression of his views.”

Further Reading:

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback by James Haskins (Macmillan, 1973).