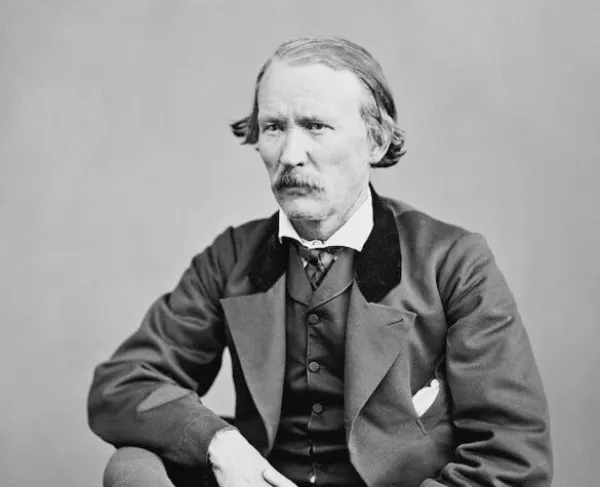

George H. "Maryland" Steuart

One of the few Confederate generals who hailed from Maryland, George Hume "Maryland" Steuart was born on August 24, 1828, in Baltimore. He was raised on his family’s plantation Maryland Square. He was descended from a long line of military men, including his father, who served as a Major General in the War of 1812, and grandfather, who served as a physician in the American Revolution.

Steuart continued his family’s military tradition by attending West Point, graduating second to last in the class of 1848, a class that also included John Buford and William “Grumble” Jones. After graduating, Steuart was assigned to frontier duty as a second lieutenant in the 2nd United States Dragoons. While on assignment in Kansas, he met his future wife Maria Kinzie, whom he married in 1858. Their marriage was a troubled one, strained by Steuart’s long absences and Kinzie’s loyalty to the Union.

After the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, Steuart resigned from the US Army and was named a cavalry captain in the Confederate Army. He then tried convincing Maryland officials to secede from the Union, which ultimately proved futile.

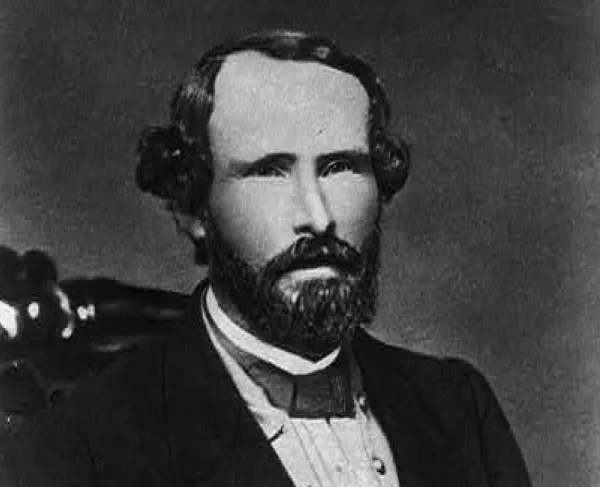

Steuart was then made lieutenant colonel of the 1st Maryland Infantry, a regiment compromised entirely of Marylanders who snuck across the Potomac River to serve the Confederacy. The regiment was championed by another Marylander, Bradley T. Johnson, who believed that Maryland should be represented in the Confederate Army, despite its refusal to officially secede.

Because his name was constantly misspelled, Steuart was given the nickname “Maryland” to distinguish him from the Confederate cavalry general, J.E.B. Stuart, of whom he had no direct relation.

After the 1st Maryland took part in the charge that led to the rout of the Union Army at First Bull Run, Steuart was promoted to colonel of the regiment. As commander of his fellow Marylanders, he displayed a strict and often eccentric style of leadership. According to contemporaries, he would sneak through his regiment’s lines to test his sentries. In one instance, a surprised sentry beat Steuart, not recognizing his commanding officer. These antics made Steuart unpopular at first, but according to accounts of some in the regiment, he grew to be respected and admired in the way he strengthened the regiment’s health and morale.

Steuart was then promoted to Brigadier General on March 6, 1862, now commanding a brigade under General Richard S. Ewell that contained the 1st Maryland. His brigade took part in General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, with engagements at Front Royal and Winchester. The brigade successfully repulsed Federal attacks at Cross Keys, but Steuart was seriously wounded in the shoulder and out of action for several months.

He would next see action in the Gettysburg Campaign. When the Army of Northern Virginia crossed into Maryland, the native Marylander is said to have leapt off his horse and kissed the soil. Afterwards, in another show of Steuart’s eccentric personality, Quartermaster John Howard recollected that he performed “seventeen double somersaults” while whistling “Maryland, My Maryland.” He and many of the 1st Maryland felt love for their home state and hoped the Gettysburg Campaign would culminate in her liberation.

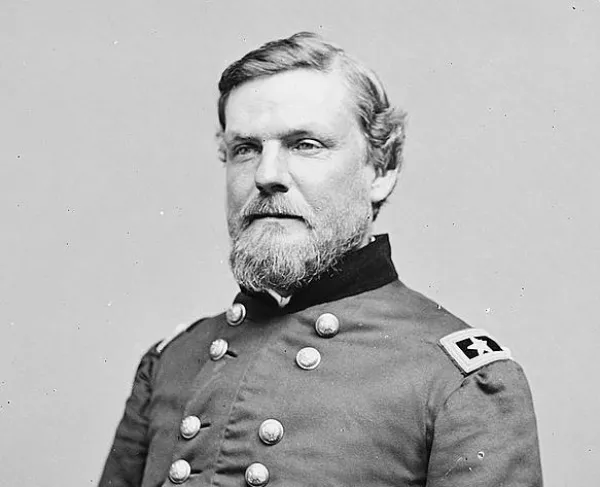

Now commanding a brigade in General Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division and in General Ewell’s corps, Steuart took part in the many Confederate attempts to dislodge Union troops on Culp’s Hill, at the very right of the Union Army’s flank. Culp’s Hill shielded the main Union supply and communication line along the Baltimore Pike, so Union General George Meade considered it paramount that Culp’s Hill was held. However, after General James Longstreet’s attack on the left flank of the Union Army in late July 2, Culp’s Hill was depleted of defenders – so much so that the nearly 5,000 Confederates outnumbered the less than 1,500 Union men left on the hill. However, the Union defenders had constructed a series of earthworks, and in combination with the rugged terrain, Confederate attackers had a difficult task ahead of them. Steuart’s brigade took part in the unsuccessful attacks on late July 2, gaining some ground near Spangler’s Spring and along Lower Culp’s Hill, and as night fell, could only listen with apprehension as Federals reinforced the section with men and artillery. The next day, Steuart’s position was bombarded by these new guns; they suffered terrible casualties and ran out of ammunition but held their position. Later than morning, General Johnson ordered a bayonet charge against the well-fortified enemy lines. Steuart was horrified by such an order, but reluctantly carried it out. The result was prophetic of the infamous Pickett’s Charge later that day, described by Steuart’s aide-de-camp Reverend Randolph McKim as a “slaughter-pen, from which…there could be no issue but death and defeat.” About 700 men of the 2,000 casaulties of Johnson’s division were from Steuart’s brigade. Steuart was said to have wept over the casualties, crying out “My poor boys!”

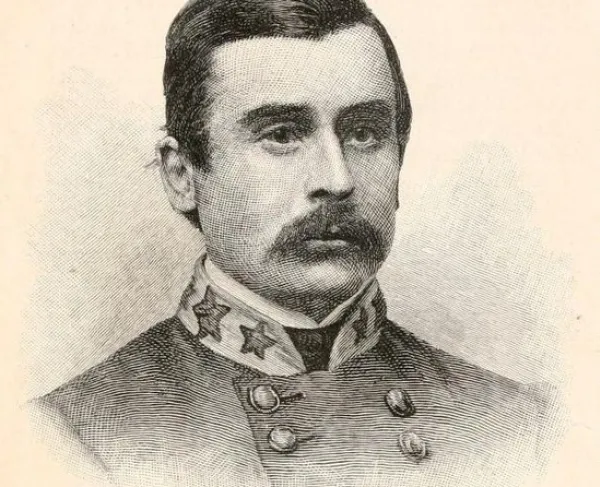

Steuart successfully led his infantry at the Battles of Mine Run and the Wilderness. However, his fortunes reversed at Spotsylvania. His brigade was involved in the brutal, close quarters fighting at the Mule Shoe, where his brigade was all but wiped out by General Winfield Scott Hancock’s Union II Corps. Steuart himself was captured by a Pennsylvania colonel. When asked to surrender his sword, Steuart sarcastically responded, “Well, suh, you all waked us up so early this mawnin’ that I didn’t have time to get it on.” Steuart was then brought to General Hancock, who knew him from their shared experience in the regular army before the war. General Hancock politely extended his hand to Steuart and asked, “How are you, Steuart?” But Steuart haughtily refused to shake the general’s hand, disregarding their old friendship for their current enmity. “Considering the circumstance, General, I refuse to take your hand,” he curtly replied. An annoyed Hancock then replied, “Under any other circumstances, general, I should not have offered it.” Afterwards, Steuart supposedly lashed out at a major who offered him a horse to ride to the rear, yet another testament to his eccentric personality.

Steuart was then imprisoned at Hilton Head, South Carolina, but was exchanged in the summer of 1864. He then commanded a brigade under General George Pickett, of Gettysburg infamy, during Petersburg, Five Forks, and Sayler’s Creek, before surrendering with General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox.

After the war, Steuart swore an oath of loyalty to the Union and returned to Maryland to tend to his family’s plantation at Mount Steuart. He eventually served as commander of the Maryland division of the United Confederate Veterans. He died on November 22, 1903, of an ulcer. He was buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, the resting place of another Maryland Confederate Isaac Trimble, as well as John Wilkes Booth.