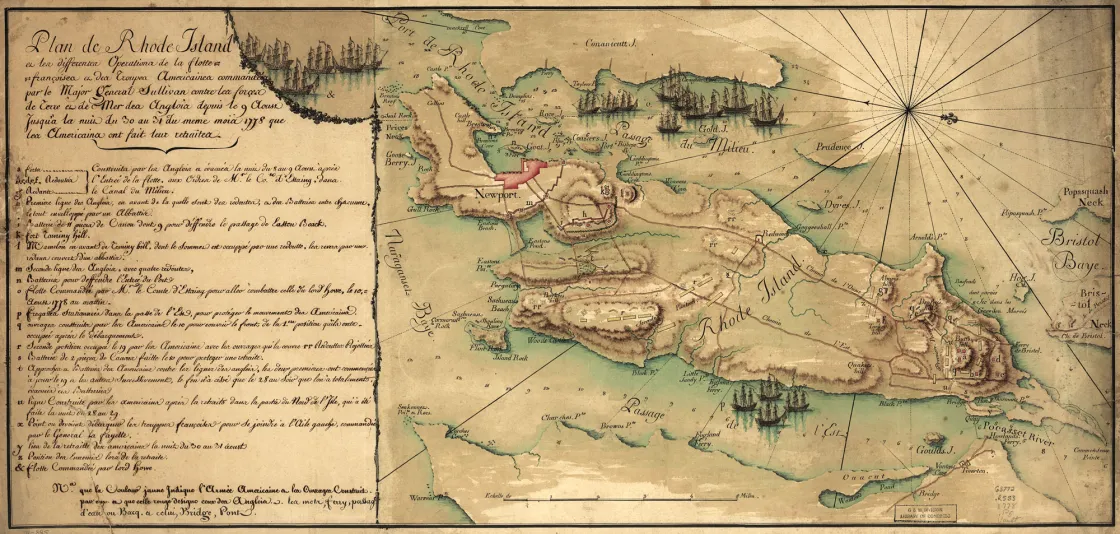

Historical map of the Battle of Road Island.

The Battle of Rhode Island was planned as a combined operation between the Americans and their new French allies, to trap and defeat a British army. Unfortunately, this grand design never came to pass.

The British occupied Newport and the rest of Aquidneck Island in December 1776. The city, then the fourth largest in America, provided the Royal Navy with an excellent base of operations, with neighboring Narragansett Bay offering an expansive and protected natural harbor. The occupation inflamed American passions. John Adams wrote that “If they are not crushed I will never again glory in being a N.E. [New England] man.” Samuel Adams echoed the sentiment: “I fear New England will be charged with the loss of her former military pride if it is not done.” There were two attempts to take Newport with militia forces in 1777, but they both ended in failure. The Americans found more success with smaller raids: A nighttime attack on July 10 managed to capture Major General Richard Prescott, the commander of the British garrison. Prescott would eventually return to active service after being exchanged for American Major General Charles Lee.

In 1778, France signed a Treaty of Alliance with the United States. The French then dispatched a fleet of 16 warships to North America, led by Charles Hector, Comte d’Estaing. General George Washington suggested that the French assist Major General John Sullivan in capturing Newport. D’Estaing agreed, and the French fleet arrived in Narragansett Bay on July 29, 1778. The French fleet greatly outmatched the 11 British warships on station. Between July 30 and August 8, 1778, the British stripped their warships of guns, ammunition and supplies, and then burned or scuttled them to prevent their capture. While the British commander, Major General Robert Pigot, second baronet, had more than 5,000 troops — including British regulars, Hessians and American Loyalists — on the island, he faced a Franco-American army of nearly 16,000 men: 2,500 Continentals and 4,000 French troops, bolstered by state troops and militia.

The French and Americans were landing their troops on the island on August 9, 1778, when a lookout on the French flagship spotted a British fleet on the horizon. D’Estaing halted the landing of the French troops and sortied out to meet the British. On August 11, 1778, a two-day nor’easter known as “the Great Storm” inflicted serious damage to both fleets. D’Estaing reappeared off Newport on August 20 with 12 battered ships. He informed General Sullivan, who had begun a siege of the city, that his fleet needed repairs and he would be sailing immediately for Boston. The decision left many American officers fuming. Sullivan was so harsh in his criticism of the French that it was rumored that the Marquis de Lafayette was going to challenge him to a duel.

The departure of the French fleet caused many American militia units to leave the army, and it left the Americans unable to block any British reinforcements. General Sullivan decided to end the siege and withdraw. The American army, which had shrunk to just over 5,000 men, left its siege works on the evening of August 28, 1778. The next morning, the British discovered that the enemy was gone. General Pigot ordered an immediate pursuit, hoping to catch the Americans on the march.

The opening engagement of the Battle of Rhode Island began at 7:00 a.m. on August 29, 1778, when British and Hessian troops made contact with the American rear guard. The Americans conducted a successful fighting retreat to a defensive line anchored on Butts Hill and Durfree’s Hill. Durfree’s Hill became the center of battle and the target of several attacks by Hessian and Loyalist troops under Major General Friedrich von Lossberg. The hill was defended by the First Rhode Island Regiment — a unit with a large number of Black soldiers, including enslaved men who received their freedom in exchange for their service. Even with the support of cannon fire from British warships offshore, the British were unable to break through the First Rhode Island. The battle ended in a draw: The British had pushed the Americans back from Newport, but the American position had held against sustained assault. Total casualties were 30 American soldiers killed and more than 100 wounded, while the British force lost 38 killed and more than 200 wounded.

Sullivan completed his withdrawal off Aquidneck Island on August 31, 1778 — only one day ahead of a British fleet carrying more than 4,000 reinforcements. Newport remained in British hands until October 25, 1779, when British Commander-in-Chief Sir Henry Clinton redeployed the garrison in preparation for the Southern Campaign. The British left behind a community hard-hit by war: The population had fallen to half its pre-war level, and the closure of the port had devastated the local economy.

The Newport Campaign was the first instance of cooperation between French and American military forces in the Revolutionary War, and it was not a positive start. But the story of Franco-American joint operations that began, however unsteadily, at Rhode Island would culminate three years later with victory at Yorktown.

Related Battles

181

260