Ambulance train at Harewood Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1863.

Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans is most commonly associated with the battlefield, but he also played a role in developing the Civil War’s most commonly used ambulance. It’s hard to imagine the U.S. Army without ambulances, but that was generally the case before the Civil War.

Prior to the conflict, wounded men had been hauled off the battlefield in whatever wagons were available, and it wasn’t until the late 1850s that the U.S. military began to try and develop specialized vehicles for wounded removal. Many of the early designs were heavy and required four horses or mules to pull them.

From December 1861 to March 1862, Rosecrans lived in Wheeling, Va., while he commanded the Department of West Virginia and led troops in some of the first fighting of the war, including the Battle of Rich Mountain on July 11, 1861. Rosecrans recognized the need for a light, nimble ambulance that could navigate the region’s rough terrain, and fortunately for him, he had a progressive young surgeon, Major Jonathan Letterman, as his medical director.

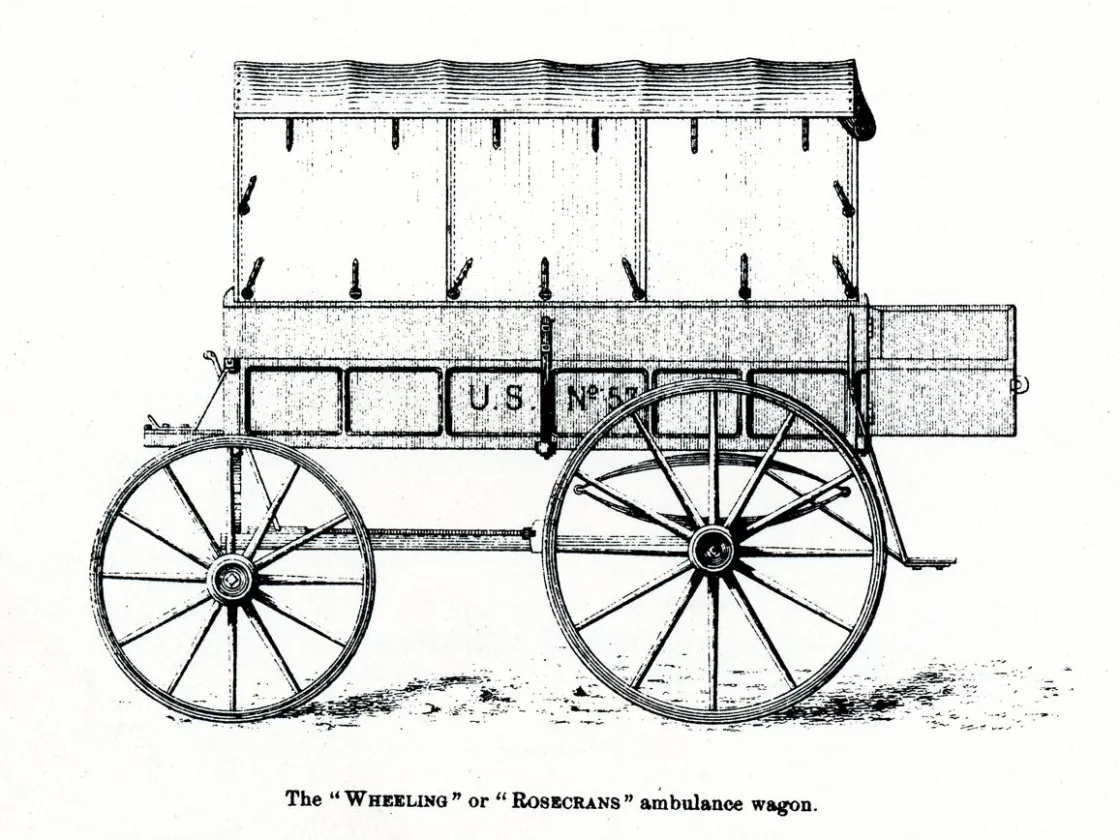

Letterman’s medical knowledge combined well with Rosecrans’ West Point engineering background to design an ambulance that helped thousands of soldiers survive their wounds. The ambulance was first produced in Wheeling’s wagon shops, and it became known as the “Wheeling,” or “Rosecrans” ambulance.

The Ambulance was lightweight (750 pounds), and only needed two horses or mules to pull it. On padded seats covered with washable oilcloth, it could carry 11 or 12 seated men. The seats could be reconfigured into a flat platform that could accommodate two to four recumbent patients. The ambulance also carried five gallons of water, and medical supplies could be kept in a compartment under the driver’s seat. Suspension springs helped reduced the jarring on injured passengers as the ambulance navigated rough roads and battlefields.

There were a number of ambulance models used during the war, but the Rosecrans ambulance was the most widely used, and is frequently seen in images.

The Ambulance Corps

Major Letterman’s star in the Union Army continued to ascend, and by the spring of 1862, Surgeon General William Hammond appointed Letterman as the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac. In August 1862, then-army commander George B. McClellan issued General Orders 147, a series of medical reforms developed by Letterman, which included the institution of an ambulance corps for the first time in U.S. Army history. A well-organized ambulance corps was key to making Lettermans’ plan work.

The order also consolidated all the ambulances of a brigade into one unit. One 4-horse ambulance and two 2-horse ambulances accompanied each regiment, and each ambulance had two stretcher-bearers and one driver who were trained in how to safely move wounded men rather than how to treat them.

Prior to having a formal Ambulance Corps, officers assigned rank-and-file soldiers as stretcher bearers—and they were usually musicians or soldiers thought to be the most unfit for battle. Once the Ambulance Corps was established, however, men were usually chosen for it based on their aptitude for helping the wounded.

That was a profound change in the removal of the wounded from the battlefield. Letterman’s order brought structure to the use of ambulances, and also called for selected, well-trained men to be in the corps. No longer would the “weakest” soldiers be sloughed off to ambulance duty. In the words of Letterman’s biographer, Scott McAugh, the establishment of an ambulance corps changed the retrieval of wounded men from a “post-battle scavenger hunt to one marked by military discipline.”

Gettysburg Campaign

During the Gettysburg Campaign, Thomas Livermore served as the head of the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps ambulance train. He recalled that “The ambulance corps consisted of three trains, one for each division of the army corps.” Forty ambulances, mostly of the Rosecrans’ model, made up each train, in addition to forage wagons for the horses and a traveling blacksmith’s forge for vehicle repair.

Livermore said had “13 officers, 350 to 400 men, and 300 or more horses, with a little over 100 ambulances” and assorted other service wagons under his command during the campaign into Pennsylvania.Extrapolating out that number, it can be estimated that about 800 ambulances and 1,600 stretcher bearers were at Gettysburg. In his official report of the Battle of Gettysburg, Letterman wrote that in the ambulance corps “1 officer and 4 privates were killed and 17 wounded while in the discharge of their duties,” proof of the hazards associated with removing wounded men under fire.

“The ambulance corps throughout the army acted in the most commendable manner during those days of severe labor,” boasted Letterman. He estimated that of the “14,193” wounded of which he was aware, “not one wounded man of all that number was left on the field within our own lines early on the morning of July 4.”

Medical Revolution

Of course, the removal of wounded men from Civil War battlefields always retained an element of chaos. Injured soldiers could be overlooked by the most conscientious stretcher bearers, and many hurt soldiers made their own way to hospitals without much assistance. Furthermore, some officers paid more attention to the needs and importance of the ambulance corps than others.

Still the development of serviceable ambulances and a structure to use them properly had a revolutionary impact on American health care. Before the Civil War, few Americans had ever seen or heard of an ambulance. But their heavy use during the conflict changed that.

Soon after the war ended, Commercial Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio, became the first major urban hospital to establish a civilian ambulance service, followed by New York City’s Bellevue Hospital in 1869. The efficient, care-giving ambulance services we are all well accustomed to and expect as a part of our lives harken back to the Civil War’s war-savaged battlefields and the innovations of a young military doctor.

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine owns a full-scale reproduction Rosecrans ambulance, as well as a three-quarter scale Rucker ambulance, a later war model that contained the best features of the Rosecrans and other ambulances. The ambulances are displayed in the Pry Barn on the Antietam National Battlefield and are also used at outreach educational events. The Museum’s Frederick, Md., location tells the story of the comprehensive medical changes, many instituted by Jonathan Letterman, that took place during the Civil War.