Stephan Hopkins

Explore the life of Stephen Hopkins, who traveled on the Mayflower to Plymouth in the New World and served as the principal person to engage with the Native Americans on behalf of the colony.

This quote from Jonathan Mack's book A Stranger Among Saints: The Man Who Survived Jamestown and Saved Plymouth, describes Stephen Hopkins' possessions at the end of his life when Miles Standish and William Bradford were witnessing Hopkins' last will and testament:

"It was a typical Plymouth household, although it did contain one rather unique item: a pale green rug. It would have shown years of hard use…. The rug was probably special to him. It was special to the entire colony of Plymouth. On this rug, the first governor of the colony sat with Massasoit. Without Massasoit's assistance, the English settlers would never have survived that first critical year. Without their Native American allies, who showed them the proper way to plant and fertilize what would become the colony's first staple crop. The first Thanksgiving would never have happened. Instead of corn and deer and laughter, there would have been mounded graves and mourning. And without Hopkins' hand in those first tense meetings with the natives, there wouldn't have been a treaty.

In his house, Hopkins had entertained and lodged Samoset and Squanto, two emissaries from Massasoit. On this green rug… Hopkins and his Native American guests sat over several days and evenings likely talking about… the alliance that the English wanted to develop with the Wampanoag. The conversation and good company helped strengthen slender bonds…. Convinced by Hopkins' hospitality, Samoset then likely persuaded the great Massasoit to enter into the momentous accord."

Stephen Hopkins was born in 1581 in Upper Clatford, a rural village 15 miles north of Winchester, England, where His father, John, was a tenant farmer. The Hopkins family moved to the city of Winchester when Stephan was five. John Hopkins passed away when Stephen was twelve years old, leaving the family in a dire financial situation. Remarkably, Stephen was able to continue his education at Winchester College, which accepted students from the poorer classes on scholarship.

Stephen remained in Winchester, married, and had three children, Elizabeth, Constance, and Giles. When he was 28, he was offered the position of clerk to the chaplain on the third fleet going to Jamestown. This third fleet of nine ships was a critical concern for England. Jamestown was failing and was England's principal point of engagement in the new world.

In 1609, Hopkins departed on the Sea Venture, the lead ship of nine, with fellow passengers, including two Native Americans returning to the New World. All went well until the Sea Venture encountered a hurricane that drove the ship onto reefs off the coast of Bermuda. The ship was destroyed, but the passengers managed to get ashore. Life was good in Bermuda – with plentiful food and a pleasant climate. Some of the passengers contemplated staying in Bermuda, including Hopkins. The leaders, though, regarded this as mutiny, punishable by death. Hopkins was sentenced to die but gained a pardon from Governor Gates.

During the nine months the castaways spent in Bermuda, Hopkins learned the language of the two Native Americans in their party. Eventually, the crew and passengers built two ships and continued to Jamestown. Unfortunately, conditions were harsh, and most colonists died during the first two years. Hopkins served as the chaplain's clerk but was also instrumental in reaching out to the Powhatan. Part of his responsibility likely included assisting at the wedding of John Rolfe and Pocahontas. By 1616, Hopkins fulfilled his indenture, and upon receiving news that his wife had died, he returned to England to care for his children.

After his return, Hopkins remarried, moved to London and became involved with the Pilgrims and their plan to go to the New World. While the story of the Pilgrims is generally characterized as a group of separatists seeking religious freedom, in reality, it was first a commercial enterprise supported by the Merchant Adventurers commercial group. The Merchant Adventurers sought out Stephen Hopkins to join their venture for his extensive experience in the New World and with the Native Americans, hoping it would benefit their expedition. Despite the danger of the voyage and the New World, Hopkins signed on to this next adventure.

Stephen Hopkins, his pregnant wife Elizabeth, his children Damaris 2, Constance 14, Giles 13, and two servants Edward Doty and Edward Lester departed on the Mayflower from Southampton on August 5, 1620. On the voyage, Elizabeth gave birth to a baby they named Oceanus.

After 65 days at sea, the crew of the Mayflower sighted land – Cape Cod. They anchored offshore and sent groups to explore the area. Hopkins accompanied these first expeditions as they anticipated meeting Native Americans. He was among the men who made the 'first encounter' with the Nauset.

In addition to building homes in the middle of winter, the Mayflower passengers faced two significant challenges – disease and starvation, and the Native Americans. Of the 102 settlers, half died in the first months. Remarkably, the Hopkins party, including their two servants, survived. However, baby Oceanus did pass away.

The Wampanoag were the Native Americans in the region that included Plymouth. A smaller subset of the Wampanoag – the Nauset – lived on Cape Cod. The settler's first encounter and subsequent interactions were with the Nauset. Wary of the Wampanoag, the settlers built defenses and an enclosure. The Wampanoag chief, Massasoit, was wary of the settlers as well, as there had been multiple killings of Native Americans and captures for the purpose of enslavement.

In March of 1621, a single Native American named Samoset walked into the middle of the settlement. While Massasoit sent him, he was from another tribe and could speak some English. He announced, "Welcome Englishmen. Welcome Englishmen" to the settlers. Between Hopkins' knowledge of Algonquian and Samoset's limited English, they were able to communicate.

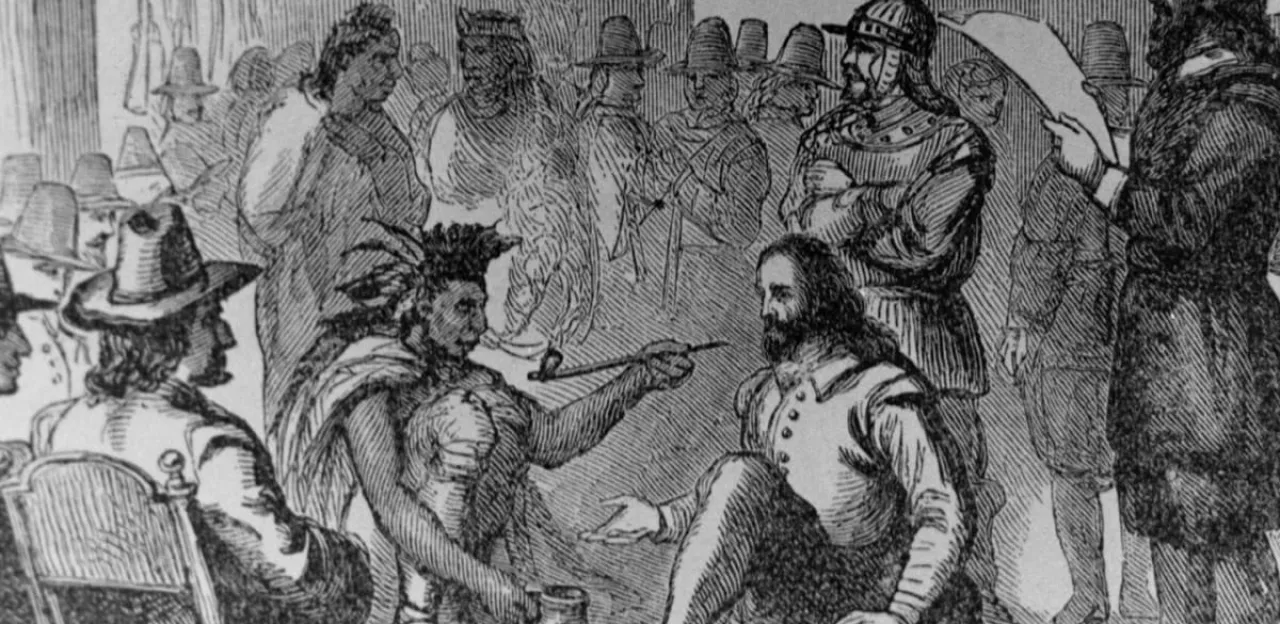

The next day, Samoset returned to the Wampanoag and brought five additional warriors and furs back to Plymouth for trading. A few days later, Massasoit himself and 60 warriors arrived at Plymouth. Included was Squanto, who had been to England and spoke English. The settlers and the Wampanoag exchanged representatives, and from that came an agreement to meet to form a treaty. Hopkins brought a green rug and cushions to the meeting place.

Samoset did not return, but Squanto remained in Plymouth. In July, with Squanto as their guide, Hopkins and Edward Winslow traveled forty miles to Pokanoket, the home of the Wampanoag chief Massasoit. They presented him with gifts, including a red horseman's coat. That fall, celebrating a successful season, Massasoit and 90 Wampanoag returned to Plymouth to join the settlers in the first Thanksgiving, the story known to nearly everyone.

In succeeding years, Hopkins remained in Plymouth, serving as the assistant to the Governor. His early work establishing peace with the Wampanoag was a model noted to subsequent settlers. Later, he opened a tavern, which occasionally had him afoul of the law. His son Giles and daughter Constance moved to Cape Cod and founded the town of Eastham. Hopkins died in 1644

Epilogue

Stephen Hopkins is my grandfather, eleven generations removed. I learned about Hopkins through my grandmother Helen Bard Davies. I knew she was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and I was curious about her—and my—Revolutionary War ancestor. I went to DAR Constitution Hall with a friend and learned about Nathan Kingsley, who fought in the Revolution. Learning more about him, I traced my ancestry back to Stephen Hopkins. Over the past few years, I have traveled to the locations where Hopkins lived and traveled: to Upper Clatford, Winchester, Hursley, and London in England, to the beach in Bermuda where he came ashore, to Jamestown, and Cape Cod and Plymouth. I have thoroughly enjoyed this pursuit. This story has been drawn from my personal research, Ancestry.com, travels, and two outstanding books on Hopkins: A Stranger Among Saints by Jonathan Mack and Here I Die Ashore by Caleb Johnson.