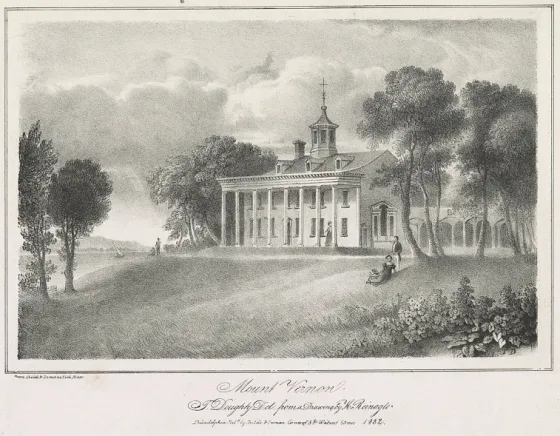

The mansion at Virginia’s Mount Vernon is synonymous with its most famous occupant, George Washington. On average, one million people travel each year to see the home of the first President of the United States. But the history of Mount Vernon spans five centuries, from the seventeenth century to the modern-day.

In 1674, George Washington’s great-grandfather, John Washington, secured a land grant along the Potomac River The land was passed down the Washington line until it came into the possession of Augustine Washington, George Washington’s father. In 1734, Augustine Washington moved his family, including a two-year-old George, into a new one-and-a-half story home built on a property called Little Hunting Creek. This home would become the core of the Mount Vernon mansion. Augustine and his family lived at Little Hunting Creek for several years and then moved to Ferry Farm, across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, Virginia.

When Augustine died in 1743, Little Hunting Creek passed to his son Lawrence Washington, the half-brother of George Washington. Lawrence renamed Little Hunting Creek “Mount Vernon” in honor of the British Admiral Edward Vernon under whom Lawrence had served as a commander of Virginia colonial troops in the War of Jenkins’ Ear. After Lawrence died of pneumonia, George Washington began renting Mount Vernon from Lawrence’s widow. When she died in 1761, Mount Vernon officially passed into George Washington’s ownership.

George Washington expanded the house that his father had built by first adding a full second story, and then erecting a wing onto each side of the house. By 1787, George Washington had transformed the 3,500 square foot home that had been built by his father into an 11,000 square foot mansion. Washington also modified the outside appearance of the mansion. Using a technique called rustication, yellow pine boards were carved to look like cut blocks of stone and then covered in wet paint and sand. The end result was a wooden structure that appeared to be made of stone.

George Washington also expanded the amount of land in his estate; between 1757 and 1786 he acquired more than 5,000 additional acres of land. When George Washington died in 1799, his estate covered nearly 8,000 acres with roughly half under cultivation and the rest largely undeveloped woodland.

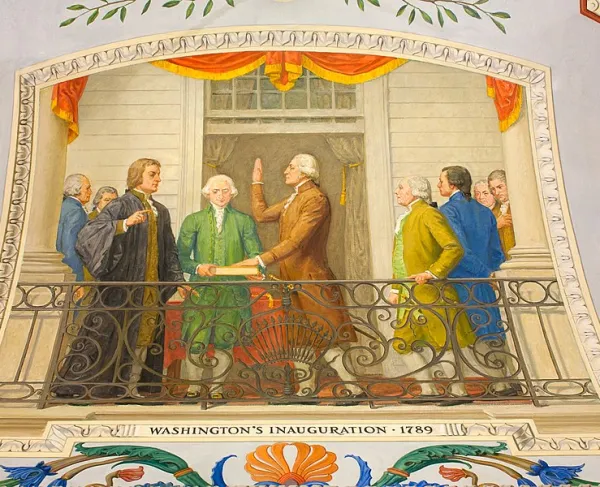

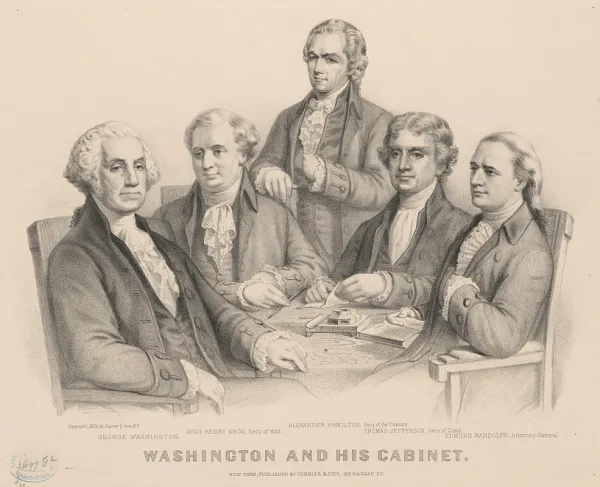

George Washington built himself a magnificent house, but he spent very little time in the finished building. During his eight years commanding the Continental Army, he returned to Mount Vernon only once. Then, as the first President, he spent much of his time in the capital (first New York City, then Philadelphia). After declining to run for a third term, Washington finally returned to Mount Vernon and found himself inundated by visitors. In 1798, George and Martha hosted as many as 677 guests over the course of the year.

George and Martha Washington’s way of life depended upon slavery. By 1799, more than 300 enslaved people lived and labored on the Mount Vernon estate. George Washington’s time as a slave owner began when his father’s will made him the owner of eleven slaves. He purchased, inherited, and rented additional enslaved people over the course of his life. When he married Martha Dandridge Custis, she brought eighty-four slaves with her as part of her dowry. Since enslaved children inherited the status of their mothers, by 1799 nearly half of all the enslaved people on George Washington’s estate were “dower slaves,” technically the property of the Custis estate.

While George Washington did not do or publicly say anything against slavery during his life, he is the only slave owning Founding Father to free any enslaved people in his will. George Washington’s will granted one enslaved servant, William Lee, his freedom immediately upon Washington’s death. The remainder of Washington’s slaves were to be freed upon the death of his wife. Martha Washington, fearing that the enslaved people would try to hasten the end of her life to gain their freedom, freed them a year after his death. However, this act of emancipation only applied to those people Washington owned outright. The “dower slaves” remained enslaved and were divided up among Martha’s heirs when she died in 1802.

After Martha died, Mount Vernon became the property of Bushrod Washington, the nephew of George Washington. Bushrod left the estate to his nephew, who in turn left the estate to his son. John Augustine Washington III, George Washington’s great-grand-nephew, was the last Washington to own Mount Vernon. By the late 1850s the estate had shrunk from 8,000 acres to 1,200 acres, and the mansion was falling into disrepair.

John Augustine began trying to sell Mount Vernon. In 1853, Ann Pamela Cunningham formed a national organization called the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, with the goal of purchasing the mansion in order to preserve it for future generations. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association purchased the mansion and two hundred acres of land in 1858 for $200,000.

Today, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association continues to operate Mount Vernon as a museum and historic site, without state or federal funding. The Ladies’ Association works to make people aware of the ways that George Washington’s legacy remains relevant in the twenty-first century.

Further Reading: