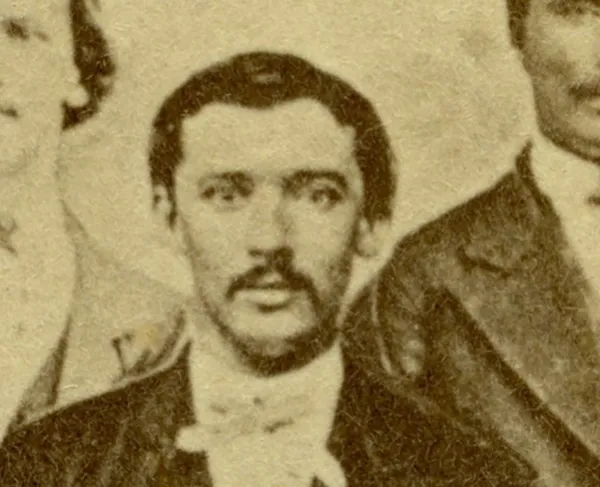

William "Billy" Lee

William “Billy” Lee was an enslaved man who acted as General George Washington’s personal manservant during the American Revolution. In 1767, George Washington purchased brothers William and Frank Lee from Mary Lee of Virginia. William cost £61.15. Washington intended to make the brothers house servants, and William, often called Billy or Will, became Washington’s valet, as well as a favorite huntsman. Lee was likely born around 1750. Washington’s records referred to Lee as “Mulatto Will,” suggesting that Billy and Frank were born to an enslaved mother and white father. Lee was among Washington’s most trusted servants, and he remained close to the patriarch of Mount Vernon throughout the duration of the Revolutionary War and its aftermath.

When Congress appointed Washington Commander-in-Chief of Revolutionary forces in 1775, Lee followed him into the Continental Army. As Washington’s valet, Lee was responsible for grooming the horses, preparing his master’s clothing and equipment, delivering messages, and attending to the General’s needs. During battle, Lee stayed close at hand, ready to provide a sword or field glass at Washington’s request. Lee survived the cruel winter at Valley Forge and witnessed the world-shattering victory at Yorktown, marking just a few of the momentous historical events to which Lee bore witness while serving at Washington’s side.

At the end of the Revolutionary War, Lee returned to Mount Vernon with Washington. In 1775, Lee had met a free black woman named Margaret Thomas, who worked as a cook for Revolutionary officers. Lee and Margaret Thomas considered themselves to be married, although Thomas lived in Philadelphia, and no records indicate that she ever successfully relocated to Mount Vernon after the war. In 1785, Lee had an accident while surveying land with Washington, and badly broke one of his knees. Several years later, Lee broke his other knee as well, crippling him for the rest of his life.

Despite these injuries, Lee accompanied Washington to Philadelphia in 1787 for the Constitutional Convention that would determine the fate of the fledgling United States. After Washington was elected President, Lee wanted to travel to the President’s household in New York. He struggled to make the journey to Washington’s residence, even with metal braces fashioned for him by doctors in Philadelphia. Upon arrival, Lee’s injuries prevented him from continuing his service as the new President’s valet. Instead, Washington arranged for Lee to return to Mount Vernon and work as a cobbler.

The decision to let Lee stay at Mount Vernon as a shoemaker and overseer of other slaves bespoke the favorable place he held in Washington’s household. Lee was also permitted to keep his last name at Mount Vernon, another sign of his elevated status among the estate’s slaves. The provisions Washington made for Lee’s wellbeing after his accident indicated the general’s affection for his loyal servant. Lee was close to his master throughout the Revolutionary War, and historians often ponder how Washington’s affection for Lee may have influenced his views on slavery and the decision to manumit his slaves at the end of his life.

Although little is known about Lee’s personal thoughts and sentiments, surviving records unveil a few details of the slave’s life and personality. Lee became famous for his spirit and bravery, as well as his penchant for storytelling after the war. One surviving account of Lee, recorded by George Washington Parke Custis, step-grandson to Washington, recalls Lee’s fondness for fox hunting and skill as a horseman:

“Will, the huntsman, better known in Revolutionary lore as Billy, rode a horse called Chinkling, a surprising leaper, and made very much like its rider, low, but sturdy, and of great bone and muscle. Will had but one order, which was to keep with the hounds; and, mounted on Chinkling…this fearless horseman would rush, at full speed, through brake or tangled wood, in a style at which modern huntsmen would stand aghast.”

When Washington died in 1799, he freed Lee, along with 124 other slaves who would be manumitted upon the death of his wife, Martha. Lee was the only slave explicitly mentioned in Washington’s will, and under Washington’s specifications, he received his freedom immediately, in addition to $30 a year and the choice to remain on his estate. Washington notably lauded Lee for “his attachment to me” and for “his faithful services during the Revolutionary War.” Lee chose to spend the rest of his life at Mount Vernon, where he was a patriot and freeman until his death in 1810.