By William Miller

Robert E. Lee makes a spectacular entrance onto the Civil War's main stage and in less than a week, later termed the Seven Days Battles, the Federal war effort is set back almost a year.

By late afternoon on May 31, 1862, the tens of thousands of sweat-soaked, powder-grimed, battle-deafened men near the rural crossroads of Seven Pines, Virginia, might well have wondered if the sun would ever go down. They had fought for hours, wet to the knees in flooded fields or blinded or blocked by dense thickets. It had been one of the bloodiest and more brutal days in American history to that point - the second most bloody and brutal, in fact, trailing only the first day of the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee, seven weeks earlier.

Late in the day, Confederate army commander General Joseph E. Johnston went forward to gain a better sense of events. Johnston commanded the Southern army in the field near Seven Pines, east of Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. He had that day attacked a much larger Federal army attempting to capture the city. It had been a bold move, but Johnston sat on his horse calmly that afternoon near Fair Oaks Station listening both to reports from officers and to bullets as they buzzed by him. Johnston turned to admonish a subordinate for ducking in unmanly fashion and, a moment later, he felt a bullet hit his shoulder. Johnston stoically bore the pain, but seconds later shell fragments from a bursting artillery round tore into his chest and leg and knocked him from his mount. In agony and uncertain of whether he would live or die, the army commander was laid in an ambulance and started for the capital.

As darkness fell, Confederate President Jefferson Davis prayed not only for the life of the general but also of his fledgling nation, which seemed perilously close to death. The war had already lasted more than a year; tens of thousands of men had been killed or maimed on battlefields and the Federals were advancing in great strength from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. Throughout the early months of 1862, the Southern armies had suffered enormously costly defeats in Tennessee, on the Mississippi, in the Carolinas, and in the Virginia Tidewater. Now, with a Federal army of nearly 120,000 men less than ten miles from his capital and with his own army commander unable to lead, Davis knew the moment of crisis had arrived. The Confederacy could scarcely live if it lost Richmond, which served not merely as its political center but as its chief industrial city as well.

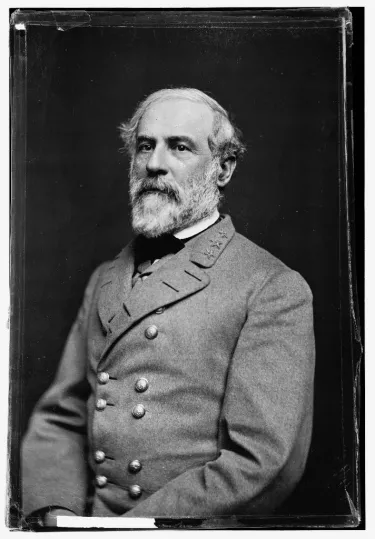

In that darkest of hours of the aspiring Confederate nation, Davis was fortunate to have at his disposal a dignified and unassuming Virginian who, during nearly 30 years of service in the Old Army, had earned the respect of his colleagues as much for his demeanor as for his excellence as a soldier and engineer. General Robert E. Lee was one of the highest-ranking generals in a Confederate uniform; however, he had never commanded an army in the field and most of his assignments in the first year of the war had ended inauspiciously. On the night of May 31, 1862, Jefferson Davis rode with the general westward from the battlefield to Richmond. The conversation between the two mounted men was not recorded, but when Davis uttered the words that placed Lee in command of the army he changed American history forever.

Lee went to work immediately. The battle at Seven Pines continued on June 1 and cost the Confederates more than 6,000 men, but the aggressive Lee had his own ideas about how to defeat the North and worried less about winning the battle than saving what men he had and embarking on a new plan. Lee believed Richmond could not be held against the enormous Federal army. The three options before the Confederate government, therefore, were to abandon Richmond, to fight a defensive battle for Richmond, or to attack. Lee personally rejected the first two alternatives and convinced Davis and his government to do likewise. He urged an attack as the best means by which to preserve Richmond Within three weeks of taking command Lee had his plan, had articulated it, and made ready to launch it.

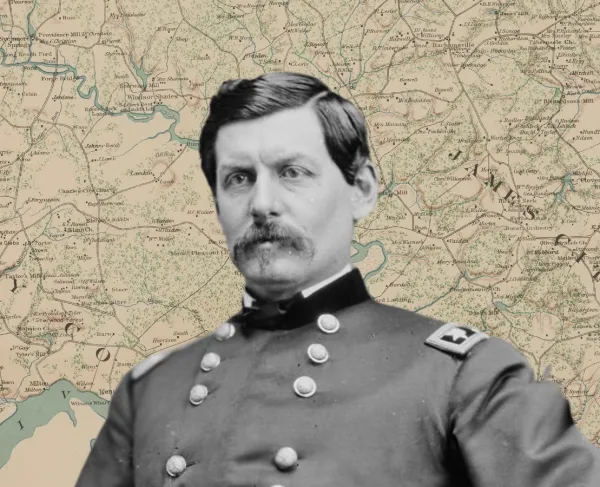

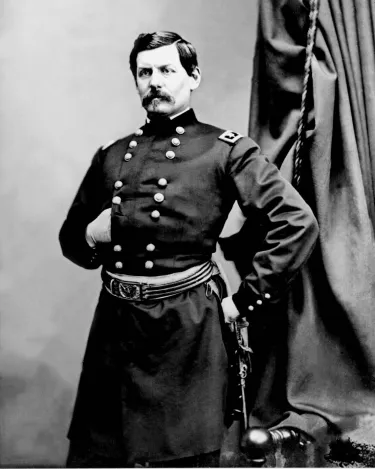

Lee detailed his plan in General Order No. 75, sent to his commanders on June 24. Though it has been called complex, in truth Lee's plan was the essence of simplicity. He required three separate columns to be prepared to march on the same morning. Each column would move on its own road, and each would march - or attack - only if the commander saw an advantage. The advantage, to be sure, depended upon the success of the other columns, but if one column did not succeed, another was not required to attack. Lee based his plan to dislodge the largest army in the history of the New World on what would prove to be an accurate understanding of the Federal position and its weaknesses. He believed that the immense size of the Federal army could actually be used against it. Major General George B. McClellan's army required more than 600 tons of food and supplies each day. The long tendrils of the Union supply line began in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Annapolis and wound southward over the waves of the Atlantic and the Chesapeake Bay and up the broad York and Pamunkey Rivers to White House, Virginia, from whence the food and supplies traveled over the Richmond & York River Railroad. The railroad provided McClellan with a lifeline, and to protect it he had to divide his army by placing part of it south of the Chickahominy River (the Richmond side) and part of it north of the Chickahominy (the White House side). From Lee's perspective, the Federals' dependence on the railroad made it an obvious target, and their deployment astride the river suggested that he might be able to attack and defeat one wing before the other wing could intervene.

But there were great risks involved. To move upon the railroad and still maintain a defensive force before Richmond, Lee would have to divide his own army. If McClellan saw through the plan and decided to throw the bulk of his troops upon the token force of 25,000 men that Lee had left in the defenses of the city, the capital might fall and Lee's plan would forever be seen as folly. Thus Lee's first offensive revealed what would become over the next two years his hallmarks: opportunism and a willingness to take risks. Lee studied the enemy, exploited his weaknesses as early as possible, and sought every opportunity to attack before he could be prepared.

Lee planned to begin his offensive on June 26, but on June 25 he suffered an anxious day. McClellan, correctly guessing that Lee was up to something, launched a preemptive attack against the defenses of Richmond just west of Seven Pines in a battle that became known as Oak Grove. After insignificant gains, the Federal commander withdrew his troops in the evening, confident that he controlled both the battlefield and the campaign. In truth, by not pressing his attack, McClellan had given Lee a great gift - more time - and Lee wasted none of it.

On the morning of June 26, 1862, all of Lee's columns were either in motion or in position to move when their turn should come. Three Confederate divisions waited south of the Chickahominy River for an opportunity to cross at two bridges. The timing of those crossings depended on the progress of a fourth division, commanded by Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Having defeated two Federal forces in the Shenandoah Valley earlier in the month, Jackson's men had stealthily hurried 100 miles eastward to participate in Lee's offensive. On this morning, Jackson was to march his 18,000 men past the Federal right flank and into the enemy's rear. Lee hoped this movement would force the Federals to abandon their strong defensive positions on the bluffs above Beaver Dam Creek. Clearing the bluffs would permit the three Confederate divisions on the south side to cross the river and, in Lee's words, "sweep down the Chickahominy and endeavor to drive the enemy from his position above New Bridge."

But Jackson did not appear on schedule and, as morning became afternoon, Lee fretted that he had lost the element of surprise. Unaware of Jackson's whereabouts, Lee decided he could wait no longer and ordered an attack with the three divisions, some 40,000 men in all, that already stood in position. Major General A.P. Hill's men moved across Meadow Bridges and drove Federal pickets and skirmishers eastward through the village of Mechanicsville. The Federal withdrawal opened Mechanicsville Bridge, and more Confederates streamed across to join the advance. North and west of the village, the Federals had placed artillery and dug gun pits on the brow of a ridge above Beaver Dam Creek. The waist-deep stream ran through a marsh and served as a moat to the Federal position. Jackson did not reach his assigned position until late in the day - well after the Confederate brigades assaulting the Federals at Beaver Dam Creek had suffered several bloody repulses. Lee lost more than 1,500 men in the futile attacks while the Federals suffered only 450 casualties.

But on the morning of the 27th, Lee learned that Jackson's flank march had had its desired effect; McClellan realized he could no longer hold the line at Beaver Dam Creek. Just before dawn the Federals withdrew. Engineers hastily selected a new defensive position three miles to the east on a plateau above a broad, sloping ravine at the bottom of which ran Boatswain's Creek. There, the Federals, some 35,000 men under the command of Major General Fitz John Porter, built impromptu breastworks of fallen trees and brush. Porter crowned the ravine with scores of artillery pieces and had reason to believe he could hold the strong position until reinforcements arrived from McClellan south of the river.

Lee had pressed his troops onward in pursuit of the Federals, and his plan of march looked very much like it had the day before. He met briefly with Jackson and instructed him to again march around the Federal right and seize a key crossroads called Old Cold Harbor. Once there, he would be within a few miles of the railroad - the primary goal of Lee's offensive - and also in position to threaten the Federals' main escape route across the Chickahominy. While Jackson moved toward the Federal right and rear, Lee would continue with the rest of the army to "sweep down the Chickahominy" to be in position to cooperate with Jackson in the afternoon.

The skirmishing began near Dr. William Gaines's mill and spread eastward as A.P. Hill's Confederates advanced. Lee was at a distinct disadvantage as he groped toward the enemy for he had no maps of any value and knew little of the terrain. The fighting intensified when Hill's men reached Boatswain's Creek, and the commanding general could do little but encourage the men and bustle about trying to learn what he could of the enemy's position. Hill's men suffered grievously in the early afternoon, but Lee felt confident that all would be well once Jackson reached Old Cold Harbor.

But once again, Jackson was delayed. In the absence of maps he had relied upon a guide, who had improperly understood his desires. After marching for a few miles toward New Cold Harbor rather than Old Cold Harbor, Jackson discovered his error, and the guide put the advance on the correct road. But the delay prevented Jackson and his nearly 20,000 men from reaching the battlefield until late in the afternoon. Lee immediately issued instructions for a general assault from the Confederate right, where Major General James Longstreet's fresh men waited in position, to the left, where Jackson might seize the Federal retreat route.

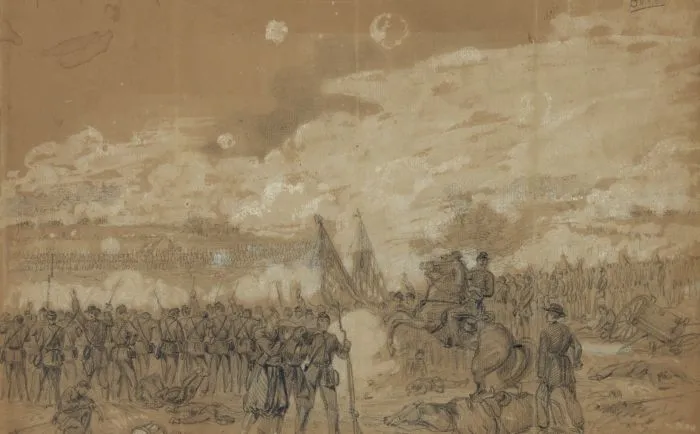

At the climax of the fighting, nearly 95,000 men clashed in combat along a two-mile front and the carnage eclipsed anything witnessed or ever before imagined by the participants. In less than half a day 15,000 men became casualties (9,000 Confederate, 6,000 Federal). In the end, however, the Confederate assaults overwhelmed Porter's defenders (McClellan had sent only a handful of reinforcements), and forced the Federals from the battlefield.

Gaines's Mill not only turned out to be Robert E. Lee's first battlefield victory, but it also secured the success of his offensive. During the night, the Federals crossed to the south side of the Chickahominy, thereby abandoning their ability to use the Richmond & York River Railroad. As a result of the defeat at Gaines's Mill, McClellan no longer had a supply line. He could not take another single step toward his goal of capturing Richmond until he had established a new line by which his men and animals could be fed. That same night, McClellan began withdrawing his army southward toward the James River where, he hoped, in a few days he would find both U.S. Navy gunboats and supply ships in plentiful numbers.

Lee had succeeded in dislodging the enormous enemy, but he did not stop to savor success. He immediately devised a plan by which he might catch and destroy in detail the fleeing Federals. Jackson would follow directly behind McClellan's army while Longstreet's and A.P. Hill's columns re-crossed the Chickahominy upstream, west of the Gaines's Mill battlefield, and tried to cut off the Federals before they could reach the James.

Skirmishing broke out at Garnett's and Golding's Farms the next day, south of the Chickahominy, but June 28 was primarily a day of hard marching for the Federals, and for Longstreet's and Hill's men as well. On the 29th, a Sunday, Jackson should have crossed the Chickahominy and advanced on the Federals, but a mix-up in orders left him marking time on the north bank throughout the day.

That same morning, the Northerners had concentrated part of their rear guard at Savage's Station, a former supply depot and field hospital complex just a few miles south of where Jackson sat. They busied themselves destroying small mountains of supplies and rations until a 14,000-man Confederate column under Major General John B. Magruder - part of the force Lee had left behind when he had launched his offensive north of the Chickahominy - emerged from the defenses of Richmond to offer battle. Now, Lee sent Magruder forward to cooperate with Jackson in attacking the Federals at Savage's Station. But Lee's staff had sent confusing orders to Jackson, and Magruder's men advanced alone against approximately 26,000 Federals under Brigadier General Edwin V Sumner. The fighting at Savage's Station ended quickly, and Sumner was content simply to blunt the advance. After suffering almost 1,000 casualties (to the Confederates' 440), Sumner withdrew through the night across White Oak Swamp, just seven miles from the James River.

Meanwhile, the long Federal column continued snaking its way southward over heavily congested and unfamiliar roads. By morning on June 30, the lead elements had reached Malvern Hill and could see the James. The rear of the army still straddled White Oak Swamp five miles back up the road. Between Malvern Hill and White Oak Swamp McClellan posted another rear guard force at a key crossroads known as Glendale. Three main roads came together at Glendale, two of which the Federals needed in order to reach the James. If the Confederates seized the intersection, McClellan knew, his army would be broken in two.

Lee, too, recognized the importance of Glendale, and by the morning of the 30th had all of his army concentrating on it from three directions. The strong column of Longstreet's and A.P. Hill's combined forces, almost 20,000 men, waited in position on the Long Bridge Road southwest of the intersection. Major General Benjamin Huger led 9,000 Confederates southeastward on the Charles City Road, and Jackson, with his own division as well as Major General D.H. Hill's - a total of more than 20,000 men - pressed southward from Savage's Station. Despite delays, miscommunications, and missed opportunities, Lee had managed to place his army in a very favorable position to deal the Federals a crippling blow. If all went well, the Confederates might destroy a portion of McClellan's army.

But all did not go well. Well-placed and well-served Federal artillery hindered Jackson's advance at White Oak Swamp, and, strangely, "Stonewall" made no vigorous effort to force a crossing. The artillerymen exchanged fire all day across White Oak Swamp, but scarcely an infantryman fired a musket. To the west, on the Charles City Road, Federal artillery likewise stopped Huger's column well short of Glendale. All that remained of Lee's three-pronged pincer movement was the combined column of Longstreet and Hill on the Long Bridge Road. Lee himself surveyed the fighting, as did President Jefferson Davis, and both came under hot artillery fire. Lee directed Longstreet to attack about four p.m. For almost six hours, well after dark, Longstreet and Hill sent their men forward. Portions of the Federal line collapsed early, but always reinforcements moved up to stop the Confederate advance. When the firing stopped, the Confederates had lost 3,600 men trying to take the crossroads and the Federals had lost 2,700 men defending it. Ultimately, the Northerners retained a tenuous hold on their real estate, and the army passed safely on to Malvern Hill and the James.

McClellan devoted most of three full corps, about 56,000 men, to defending Glendale while the rest of the army continued southward, but, surprisingly, McClellan himself did not remain to conduct the all-important defense. He rode southward to locate a safe haven for the army on the James.

Frustrated, Lee fumed about the opportunity lost at Glendale. Nearly 70,000 Confederates had been available within a few miles of Glendale, but because of poor communication and a lack of vigor among the column commanders some 49,000 Southern soldiers never made it into the fight. Lee believed he had just one more chance. He urged his generals forward on the morning of Tuesday, July 1, and they again found the Federals in defensive array, this time on the imposing heights of Malvern Hill.

Shaped like a large horseshoe, its open end facing northward, toward the Confederates, Malvern Hill featured extremely steep, wooded slopes on its southern and western sides. The northern slope of the hill hardly sloped at all and was covered by a broad, open wheat field. Federal officers posted artillery in thick masses on the top of the hill and dared the Southerners to come. Lee and Longstreet carefully examined the position and believed that they might breach the obviously strong Union line by converging artillery fire followed by a prompt and very strong infantry assault.

But once again miscommunication and poor timing doomed the Confederate plan. The Federal guns overwhelmed the Southern artillery, and the Confederate infantry, though well led and gallant as always, fell to pieces, mowed down by the peerless Union artillery. It is a testimony to the valor of the Southern infantry that they inflicted nearly 3,000 casualties under such disadvantageous circumstances. The Federals had every advantage at Malvern hill and culled 5,000 more men from the ranks of Lee's army. "It was not war," wrote Confederate General D.H. Hill, whose brigades suffered severely, "it was murder."

Lee's late June offensive would ever afterward be known as the Seven Days Battles. It might have been, in its way, as shocking to Americans in 1862 as Pearl Harbor in 1941, or the terrorist attacks in 2001. First, it had produced unimaginable carnage. It had been the bloodiest week in American history, producing more than 34,000 casualties (19,000 Confederate, 15,000 Union). Second, the reversal of fortune in the Seven Days Battles has been identified as the first great turning point in the war. For almost a year the Union juggernaut had been rolling seemingly irresistibly toward victory, and, indeed had rolled to the very threshold of Richmond. Americans (and others) who read newspapers developed expectations. The New York Times opined that the war would be over by Independence Day. But events in June 1862 proved that all the Confederate cause had lacked was a military leader of superior ability. Robert E. Lee did not seek the reins of control, but his experience, sound counsel, and impressive bearing led Jefferson Davis to give him command of the Confederacy's most important army. Within a month, Lee and his men had reversed the expectations of millions by routing the largest army the United States had ever put in the field. Those seven days remain among the most important in U.S. history because they gave new life to the Confederacy. Lee's rejuvenation of the Confederate cause began on the banks of the Chickahominy but extended across scores of future battlefields and across hundreds of miles and days and thousands of tragic deaths of principled men, North and South.

William Miller has written or edited seven books and published more than 100 articles on the Civil War including Mapping for Stonewall: The Civil War Service of Jed Hotchkiss, winner of the Fletcher Pratt Award. His next book, Great Maps of the Civil War, will be published in 2004. A former editor of Civil War Magazine, Miller is a strong advocate of battlefield preservation. He was a founding director of the Richmond Battlefields Association and has served as a director or adviser of various preservation organizations, including the Kernstown Battlefield Association, Protect Historic America, and the Save the Battlefield Coalition.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

6,800

8,700

3,797

3,673

2,100

5,600