The Deep Cut, Second Manassas Battlefield at Brawner's Farm, Manassas National Battlefield Park, Manassas, Va.

Few places in America were fought over as much as the rolling hills and plains of the Virginia Piedmont along Bull Run. Just 30 miles southwest of Washington, D.C., Bull Run stretches from the Bull Run Mountains eastward to the Occoquan River and then to the Potomac River. It is a small stream with steep banks, a natural military defensive position. Two of the Civil War’s most impactful battles took place a year apart on the same farmsteads along Bull Run. Both had major implications for the country and the local population.

The Battle of First Manassas (or Bull Run) exemplified the amateur nature of both armies at the war’s outset. Both Federal Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell and Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard devised complex plans for their armies. The Confederates used Bull Run as a defensive barrier, intent on defending as much Virginia territory as possible and protecting Manassas Junction, where two rail lines converged. These rail lines were vital for communication, supplies and reinforcements. On July 21, 1861, best laid plans were quickly overtaken by events on the field. What seemed to be a total Northern victory in the morning on Matthews Hill quickly turned to a stout Confederate defense on Henry Hill. Using the railroads, the Confederate Army of the Shenandoah under Gen. Joseph Johnston was able to reenforce Beauregard. By sundown, the Federal army was retreating from the field after a total victory for the Confederates.

Though the Federals were defeated, they were not totally routed. The gates of Washington were not wide open to the Confederates — thousands of Federal soldiers still occupied Centreville, Fairfax and Alexandria. Though disorganized, they were still a formidable force. Also, the Confederates were just as disorganized in victory as the Northerners were in defeat. Again, military campaigning was not yet a perfected skill by either side.

Many believed this would be the first and last battle of the war. As he walked among the dead after the battle, Pvt. B.M. Zettler of the 8th Georgia lamented, “Surely, surely … there will never be another battle. It seemed to me barbarous for men to try to settle any dispute or controversy by shooting one another, and now that it had been realized what a battle meant, I felt sure there would never be another.” Sadly, Zettler would be disappointed.

As the fighting in northern Virginia took a brief respite, locals such as the Connors, Robinsons, Carters, Chinns, Thornberrys and others tried to recover their farms. Damage had been caused not just by battles, but also by the vast Confederate campsites built during the winter of 1861–1862. Thousands of Southerners converged on Prince William, Fairfax and Loudoun Counties. The battlefield at Bull Run was no exception. Large camps were built along Bull Run and the Occoquan River. Here, the deadliest enemy wasn’t a Yankee soldier, but rather disease and unsanitary camp conditions. Most of these men were farm boys who had never lived in close quarters with so many others. Soon, hundreds and then thousands of men became sick and were sent to hospitals in Charlottesville and Richmond. Thousands died and were buried in Virginia, far from home.

In March 1862, the Confederates broke camp and moved south, leaving behind broken fences and destroyed barns and houses. Crops were gone and livestock missing, and ghost towns of abandoned log huts dotted the landscape. Many Confederates burned warehouses of supplies, as well as any buildings that could be used by the United States military.

The local population would have only five months of relative peace before war returned on their doorstep. Just over a year after the Battle of First Manassas, two larger, more disciplined armies returned to the banks of Bull Run. Thousands had fought and died across the continent since July 1861, and now the soldiers brought their killing expertise back to the farms in Prince William County. Federal Maj. Gen. John Pope, leading a “new” Federal army called the Army of Virginia, was tasked with putting pressure on Richmond from the north. In August 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was outmaneuvering Pope and forcing him northward. Again, the railroads would play a major role in the armies coming back to the region. Pope used the Orange and Alexandria Railroad as his basis of supply, and Jackson used that weakness to his advantage, cutting the railroad at Bristoe Station on August 26. Soon, Pope retreated north along the railroad looking for Jackson.

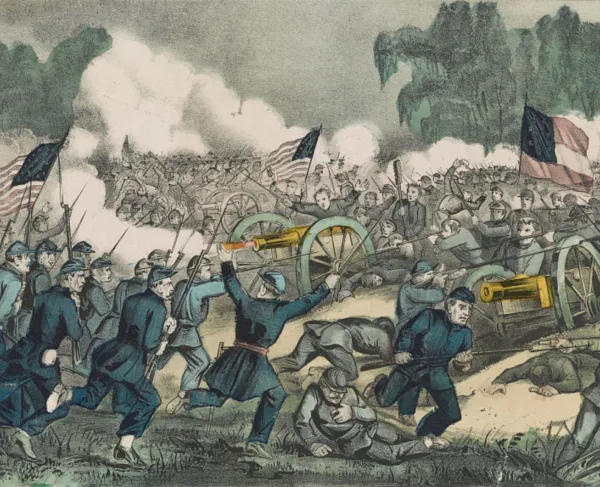

On the old Bull Run Battlefield, Jackson and Pope clashed on August 28, kicking off a three-day battle that led to nearly 22,000 casualties. Pope, focusing on Jackson’s wing of the Army of Northern Virginia, saw a chance to destroy the famed Stonewall. Pope launched numerous assaults all day on August 29 against Jackson’s line along an old unfinished railroad bed. Some attacks broke Jackson’s line temporarily, but no strategic breakthrough was won. Pope hoped that Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s V Corps would assault Jackson’s right flank and roll him up. But by August 29, Gen. Robert E. Lee and Maj. Gen. James Longstreet arrived with the other wing of the Confederate army. Pope and Porter subsequently began a dispute that would carry on for many years and eventually cost Porter his command.

Then on August 30, Pope ordered Porter to attack Jackson’s line at the “Deep Cut.” The attack was not successful and ended in a bloody repulse. Soon after, Longstreet launched a massive assault with nearly 30,000 men against Pope’s little protected left flank. Pope instantly sent units to slow the Confederate advance, at a heavy cost. Fierce fighting occurred on Chinn Ridge all afternoon. By late afternoon into evening, Pope was able to shore up his line on Henry Hill and that night escaped north toward Centreville. Another Federal army was leaving the Bull Run Battlefield in defeat. Both armies would turn their attention to Chantilly, then into Maryland and, ultimately, the banks of Antietam Creek.

The armies returned to Prince William County again in the fall 1863 at the Battle of Bristoe Station, a few miles south of the Bull Run Battlefields. By 1864, the armies had moved south, and partisans continued to fight around the Bull Run farms. The importance of the Bull Run Battlefields became evident 50 years later, when veterans from both sides attended a grand reunion dubbed the “Peace Jubilee.” For more than a hundred years since, travelers still come to visit the “plains of Manassas” to learn about where nearly 4,000 Americans perished.

Related Battles

2,896

1,982

14,462

7,387