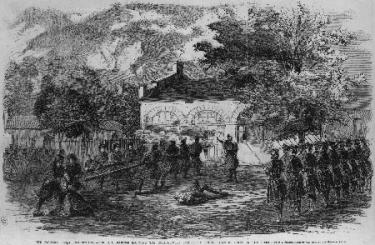

The Harper's Ferry insurrection with the U.S. Marines storming the engine house, and insurgents firing through holes in the doors.

John Brown launched his war against slavery at Harpers Ferry. Brown’s war was not a conventional war. It did not engage army against army. It did not predicate marching columns and colliding corps. It did not predict thousands of acres of battlefields with mountains of mass casualties. Brown’s grand strategy was economic war. His ground strategy was guerilla war. His tactic was mobile war.

Brown’s war plan was simple in concept, but complex in execution. Through small bands of trained and armed men, “Captain” Brown intended to assist and guide slaves in their escape from the South. The causeway to freedom would be the Appalachian mountain chain, stretching from northern Alabama into Pennsylvania. Night after night, from mountain fortress to mountain fortress, a trained army of liberators — operating in small groups — would escort the escaped slaves northward. Brown’s system would be so safe and so reliable that it would entice thousands of slaves to participate. Brown predicted this mass slave migration would dramatically devalue slave property, ultimately bankrupt the slave aristocracy and politically plunder the slave oligarchy. Slavery would dive into extinction, Brown reasoned, with no economic foundation and political perfunctory.

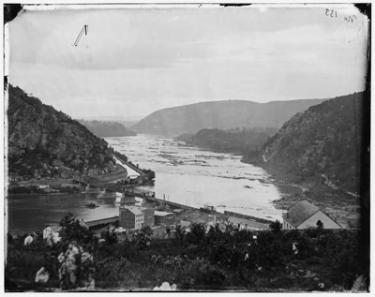

To begin his war, Brown needed firearms. The arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Va., (now West Virginia) stored 100,000 rifles and muskets. Next, Brown needed an army. Eighteen thousand slaves lived in the six counties nearest Harpers Ferry. Then Brown needed shelter and security. The formidable mountains of the Blue Ridge extended north and south from Harpers Ferry. As the initial target in his war against slavery, Harpers Ferry made perfect sense to John Brown.

Not to Frederick Douglass, however. “You are walking into a perfect steel trap,” Douglass warned Brown at a secret meeting in a quarry at Chambersburg, Pa., in August 1859. Douglass believed that an attack at Harpers Ferry, with its U.S. armory and arsenal, would ensure the immediate and vengeful wrath of the government. Despite Douglass’s entreaties and his refusal to join the venture, Brown remained convinced Harpers Ferry must be his first blow for freedom.

On Sunday night, October 16, 1859, after secretly gathering men and materials for three months at a secluded Maryland mountain farm, Brown delivered his orders: “Men, get on your arms. We shall proceed to the Ferry.”

The five-mile march from the Kennedy Farm hideaway brought Brown’s party to the Potomac River. Silently seizing the watchman at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad bridge, Brown and his 18 followers quickly and methodically captured the musket factory, rifle factory and arsenal. No shots. No shouts. No surprises … not for Brown, anyway. The raiders possessed the government property before midnight. The plan was working perfectly

Then, in the wake of three careless moments, the scheme began to unravel. First, the railroad bridge night watchman escaped his captors, promptly proceeding to flag down and halt an approaching B&O passenger train short of the station. This grabbed the attention of the station baggage porter — a free African American named Heyward Shepherd — who became curious about the train’s strange stopping point and started roaming in the 1:30 a.m. darkness. Then occurred careless action two: Brown’s men shot and fatally wounded Shepherd. The echoing gunshots awakened Dr. John Starry, who tumbled from bed and came to investigate. Brown’s men snared Starry, brought him to the dying Shepherd, and then — in the third careless act — permitted him to depart.

Dr. Starry did not return to his chambers, but rushed to the livery, grabbing a horse and galloping to nearby Charles Town. The “Paul Revere of Harpers Ferry” loudly announced abolitionists had seized the Ferry. Church and fire bells suddenly clanged into chorus, and near dawn on Monday, approximately 90 well-uniformed, well-drilled, and well-armed members of the Jefferson Guards militia were standing in formation before the courthouse. By 11:00 a.m., only 12 hours after Brown had entered Harpers Ferry, the Jefferson Guards had sealed escape routes, surrounded the armory and arsenal, segregated raider reinforcements and spoiled Brown’s scheme. Brown was trapped within his headquarters, the armory’s fire engine house.

A tense standoff followed on the afternoon of the 17th. Hostages huddled in the dreary dank brick building. Brown held townspeople, armory officials and local planters for bargaining. He attempted negotiation, but raiders carrying flags of truce promptly were shot or seized. The town mayor wandered near. His curiosity resulted in a dead aim and a dead mayor. Tempers exploded, with townspeople killing captive raiders, collecting corpses for target practice and threatening lynchings. Brown’s force dwindled as first one and then another of his sons were shot. Soon, only four raiders remained to stand with John Brown.

By midnight on October 17, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee and 87 U.S. Marines dispatched from the Washington Navy Yard under his command had arrived by train, and an assault was planned. Since flying bullets could harm hostages, the Marines would use only bayonets. An eerie quiet hovered on the Tuesday dawn as U.S. Cavalry Lt. J.E.B. Stuart, who had been in the capital for personal business and, upon hearing of the raid, volunteered as an aide-de-camp, approached the barricaded engine house doors with orders for Brown to surrender. The fiery abolitionist refused. Marines then sprang forward, using a sledgehammer and a ladder to batter the door, eventually smashing a hole large enough to allow passage for one marine at a time. Within three minutes, Brown had been wounded, the four raiders were killed or captured and all 11 hostages freed unharmed.

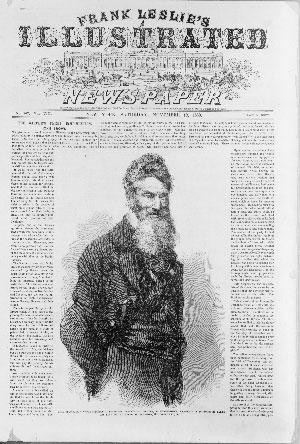

One week later, Brown was on trial in Charles Town for murder, treason and inciting slave rebellion. Deemed guilty on all three counts, Judge Richard Parker determined the noose was the answer for John Brown. On December 2, only six weeks after his capture, Brown was hanged. “I, John Brown, am now quite certain,” portended the condemned man in his final note, slipped to a jailor on his way to the gallows, “that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with blood.”

Although dead, Brown did not rest. He fanned flames North and South over the emotional issue of slavery. Northerners celebrated Brown as a hero; Southerners declared him the devil. “You can weigh John Brown’ body well enough,” extolled Stephen Vincent Benét in his 1929 epic poem John Brown’s Body, “but how, and in what balance, weigh John Brown.”

John Brown’s soul went marching on — soon to be followed by the souls of millions — into the abyss of civil war.

Related Battles

12,636

286