Throughout four years of Civil War, North Carolina contributed to both the Confederate and Union war effort. North Carolina served as one of the largest supplies of manpower sending 130,000 North Carolinians to serve in all branches of the Confederate Army. North Carolina also offered substantial cash and supplies. Pockets of unionism existed in North Carolina also resulted in approximately 8,000 men enlisting in the Union Army--3,000 whites plus 5,000 African Americans as members of the United States Colored Troops (USCT).

As the war progressed General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia became increasingly dependent on North Carolina for provisions. The ravished the Virginia countryside was making it unable to sustain Lee’s army. Consequently, Lee turned to North Carolina whose warehouses contained significant food supplies and Lee became increasingly dependent on these supply depots to the point where General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee was left with practically nothing and had to forage for food. It is important to note that Johnston’s army provided significant protection to Lee’s army by guarding the rear of the Army of Northern Virginia. This support was vital to the sustainment of Lee’s Army in Virginia.

Even before General William T. Sherman’s march through North Carolina, hardship and violence plagued the state’s civilian population. High inflation of Confederate currency devalued goods and made them harder to purchase, which aggravated the poorer civilians in the state who had an even harder time trying to make ends meet without slaves. North Carolina was one of two Confederate states who appropriated funds to the families of poor soldiers by taxing slaves and large landowners. However, these measures failed to alleviate class tensions and some women resorted to violence, such as bread riots, to achieve goods at a non-inflated price. Others encouraged their loved ones to desert to help provide for the family at home. There were a high number of desertions among North Carolina troops. Desertion brought on its own problems as families had the added anxiety of feeding and hiding a deserter while facing harassment from the home guard. The home guard often consisted of older men unfit for service who took it upon themselves to stamp out illegal behavior on the home front, often using violent tactics including torture of civilians. Civilians on the home front also experienced violence at the hands of roving bands of deserters who would often indiscriminately raid homes, with some raids even leading to murder. The violence and hardship that plagued the home front strained the bond between the Confederacy and civilians, yet Sherman’s march reinvigorated this bond. While the violence and disorder increased as Sherman arrived in North Carolina, this violence and disorder at the hands of the Union army reunited the fractured North Carolinians and re-inspired a commitment to the Confederate cause.

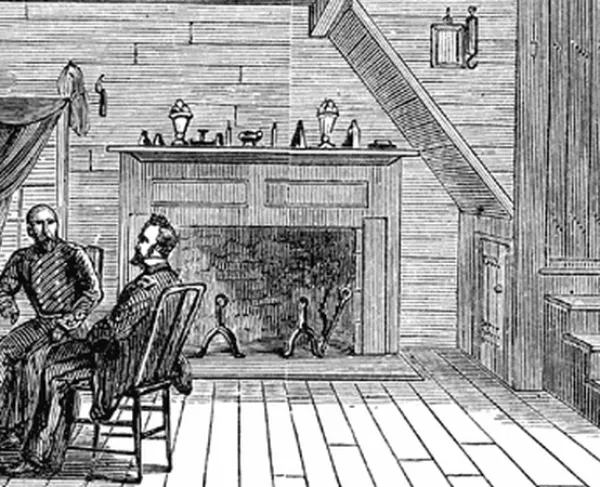

North Carolina served as a battlefront throughout the war, with a total of 85 engagements taking place in the state. However, the majority took place in 1865 with Sherman’s March and Bentonville, which is when the battlefront and home front merged into one. The Battle of Bentonville served as the largest engagement on North Carolina soil and represents Johnston’s last stand against Sherman’s army. Approximately 80,000 forces engaged at Bentonville over the course of three days of fighting. What started as a Confederate assault on March 19, 1865 quickly divulged into sporadic skirmishing and a Confederate retreat. Negotiations between Sherman and Johnston began on April 17 in the small Bennett Farmhouse outside Durham, North Carolina; however, the federal civilian authorities rejected the proposed terms because they were too lenient to the Confederacy. Consequently, Sherman and Johnson met again at the Bennett House on April 26. By the terms of the surrender Johnston’s army mustered out and paroled home at Greensboro, North Carolina. The Union army provided ten days rations and transportation home to most parolees. Men could keep their personal property and horses and each Confederate brigade kept 1/7 of their arms until they reached their respective state capital. These favorable surrender terms allowed former Confederates to return home with relative ease.

Out of the 138,000 North Carolinians who served in both the Union and Confederate Armies, 40,500 perished in the war which represents 6% of the free population, a huge blow for the state. Additionally, Sherman’s army and previous fighting ravaged the countryside. North Carolinians sacrificed greatly for both the Union and Confederate causes which created discord and tension among the civilian population. Nevertheless, North Carolina remained instrumental in supporting the Confederate war effort.

Related Battles

1,527

2,606