By the Civil War, the strategy behind cavalry had changed drastically from the Revolutionary War. Due to the advancement in rifled weapons, cavalry charges were no longer as effective as they had been in earlier wars. The role of the cavalry became largely one of reconnaissance, often being asked to scout enemy forces in order to retrieve information and to screen their own armies as they marched to their destination.

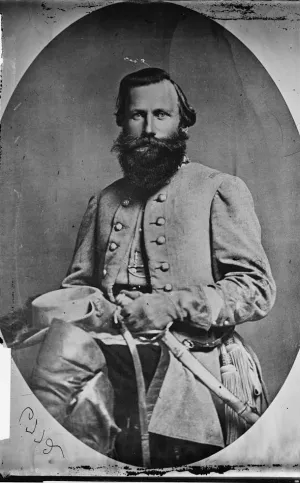

J.E.B. Stuart commanded the cavalry wing of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and, as noted in a letter addressed to Stuart from Robert E. Lee, served as the “eyes and ears” of the army. By the time of the Gettysburg Campaign during the summer of 1863, J.E.B. Stuart had established himself as both a skilled cavalryman and, as Jeffrey Wert describes him, the “Confederacy’s knight-errant… who clung to the pageantry of a long gone warrior.” Unfortunately for Stuart, his ride during the Gettysburg Campaign was plagued by surprise attacks and unknown Union movements that redirected Stuart’s path.

In preparation for the upcoming ride to the north, Stuart had his men bivouacked 6 miles outside Brandy Station, screening the Confederate army along the Rappahannock River. On June 8, 1863, Stuart held a review of his soldiers for Robert E. Lee at his camp. Following the review, Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock and raid the Union forward positions.

However, Union cavalryman Alfred Pleasonton had anticipated the attack and massed his own forces on the opposite bank of the Rappahannock River. Pleasonton called for two attacks, one by Brig. Gen. John Buford in the north at Beverly’s Ford and a coordinated effort from Brig. Gen. David Gregg in the south at Kelly’s Ford.

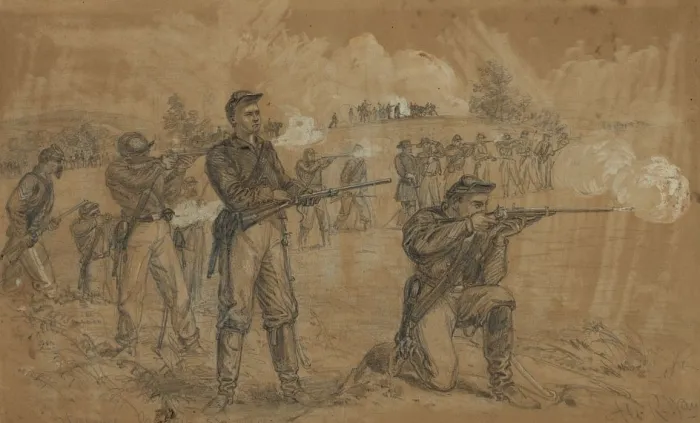

Buford and his men began their attack at 4:30 am on June 9th, scattering the surprised Rebel pickets at Beverly’s Ford. Hearing the gun shots from the Union troops, Confederate soldiers from the camp at St. James Church joined in on the fight and were able to stall Buford’s advance. The Confederate efforts, while costly, bought the artillery enough time to deploy and unleash a deadly assault on the Union column.

After overrunning the Confederate guns, but failing to maintain position, Buford refocused his efforts on capturing the guns by moving around the Confederate left by Yew Ridge. While Buford struggled with the Confederate artillery, Gregg’s attack was delayed by a small Confederate force at Kelly’s Ford. At 11:30 am, Gregg was finally in position at Brandy Station. Gregg’s artillery opened fire on Stuart’s headquarters at Fleetwood Hill and surprised the Virginian once again, as he had given his full attention to Buford’s attack.

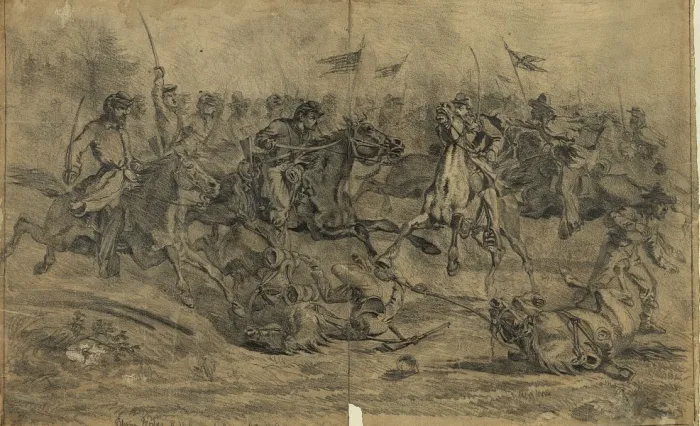

Stuart, thanks to the success of the Confederate troops at Yew Ridge, was able to shuffle more troops to defend Gregg’s attack. The two lines clashed for another five hours, and at around 5 p.m., upon hearing news of Confederate reinforcements, Pleasonton called off the attack. While Stuart was able to hold off the Union attack, it came at a great cost to his cavalry forces and his reputation, as he had been caught off guard by two surprise attacks during the battle.

Following the Battle of Brandy Station, an embarrassed Stuart led his cavalry corps as they screened the northbound Confederate infantry through the Shenandoah Valley. From June 17 to June 21, Stuart’s cavalry clashed with their Union counterparts at Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville. The fighting began at Aldie, where a brigade of Stuart’s cavalry crossed paths with Union forces and engaged in four hours of stubborn fighting.

The fighting continued two days later at Middleburg, where Stuart was unable to maintain his advantageous position on Mount Defiance. However, Stuart’s expert parrying of Union attacks kept the Union cavalry from gaining any insight on the position of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The final day of the ongoing fighting occurred on June 21 at Upperville, where Stuart’s defensive efforts were successful once again in preventing the Union forces from gaining any information on Lee’s position as he advanced his army towards Maryland.

After the various engagements with the pursuing Union cavalry, Stuart received orders regarding his role as Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began their invasion of the North. While the exact nature of Lee’s orders remain a point of contention, it is believed by many that the purpose of Stuart’s cavalry in the Gettysburg campaign was to cross the Potomac River and screen the right flank of Richard Ewell’s Second Corps.

Instead of taking a direct route to Ewell’s Second Corps, Stuart decided to take the brigades of Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and John Chambliss north toward Rockville, Maryland, moving between the Union Army, who were marching north through Virginia about 50 miles east of Lee’s army, and Washington, D.C. However, by the time Stuart began his ride on June 24, Union movement was underway and Stuart’s desired route was blocked by columns of Union soldiers. This unexpected obstacle forced Stuart’s cavalry further east than originally planned and not only hindered Stuart’s ability to reach Ewell’s right flank, but also deprived Lee of vital intelligence that a more conventional cavalry screen would have provided.

On June 28th, Stuart’s cavalry crossed the Potomac River into Rockville, Maryland, where they captured a wagon train of more than 100 fully loaded wagons. The size of the wagon train would further hinder his march to screen Ewell’s right flank. While critics of Stuart believe this to be a tactical error, the wagons were loaded with fodder which would become increasingly important as the strenuous ride took its toll on Stuart’s horses.

For the next two days Stuart and his troops proceeded towards the Pennsylvania border, taking time to sabotage Union communications. On June 30th, the cavalry corps crossed over into Pennsylvania and headed northeast toward Hanover. Upon reaching Hanover at 10 a.m., Stuart’s men were surprised to encounter Judson Kilpatrick’s Union cavalry forces. The Confederates engaged, with the battle spilling into the streets of Hanover. The battle continued throughout the day, eventually ending as both Kilpatrick and Stuart withdrew their units from the battle field. While not a tactical loss, J.E.B. Stuart lost more time and a total of 215 men.

From Hanover, Stuart continued north, arriving in Dover on July 1, 1863, just as the fighting began at Gettysburg. At this point, having been cut off from communication with Lee’s army, Stuart was unaware of the Army of Northern Virginia’s position. Stuart had grown worried and sent out various officers in an attempt to locate the army he was supposed to have reached already. By midnight on July 2, Stuart received word that Lee’s army had made their way to Gettysburg and were engaged in battle with the Army of the Potomac. By 3:00 am, the weary column was on its way to Gettysburg, with General Stuart leading the way.

The exhausted corps arrived at Gettysburg on July 2, with what artilleryman Henry Matthews described as “a grateful sense of relief which words cannot express.” Immediately upon arrival, Stuart reported to Robert E. Lee. While no firsthand accounts exist of the interaction, second hand reports from Lee’s staff officers suggest that Lee reprimanded Stuart for his failures up to that point in the campaign. Following the meeting, Stuart was ordered to ride to Ewell’s flank northeast of town.

On July 3, Stuart and his men engaged in a bloody battle with Union cavalry forces, led by Brig. Gen. David Gregg, at what has become known as East Cavalry Field. The battle began with a cavalry charge from the Confederate forces, which was countered by the 7th Michigan. The two forces engaged in intense point-blank fighting along the fences of Rummel Farm. In effort to turn the tides in his favor, Stuart sent a second charge led by Wade Hampton, during which Hampton received multiple slashes to his face at the hands of Union sabers. Eventually Union forces were able to surround the Confederates on three sides, forcing Stuart to withdraw, but Gregg’s men were in no condition to pursue them further. The withdrawal at East Cavalry Field brought an end to Stuart’s troubled ride to Gettysburg.

Related Battles

866

433

23,049

28,063

209

180