An Interview with Historian Dr. Joseph Glatthaar

By Clayton Butler

The Civil War Trust's own Clayton Butler recently had the opportunity to sit down with one the most distinguished scholars in the field of Civil War history – Dr. Joseph Glatthaar of the University of North Carolina. He shared his thoughts on the state of current Civil War scholarship and the compelling nature of Civil War history for scholars and the general public alike. As Dr. Glatthaar make clear, the field of Civil War history has only strengthened as it has expanded, and continues to be heir to an extraordinarily rich tradition of first-rate scholarship and research.

Clayton Butler: What do you consider to be the most significant findings or theories generated about the Civil War in the last ten to twenty years?

Joseph Glatthaar: Yael Sternhell’s book [Routes of War] on movement was pretty unusual. I hadn’t really thought about the issue of movement, and I think we’ve gotten some really great scholarship on contrabands lately [from] Leslie Schwalm and Thavolia Glymph. I think those are really interesting subjects. I think we’ve had lots of books on different topics and we’ve kind of nibbled around the edges for new findings, and I’m among those people. I think one of the big battles these days is about the motivations of Union soldiers and the Union cause, and I think we’ve kind of finally settled down a little bit. We’ve also had some good ‘home front’ material – more on the Confederacy than the Union – and I think one of the things that we’ve been able to really challenge are the notions about a ‘rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.’ That’s just not there. And I think we’ve been able to put dissent on the home front in the Confederacy in a little bit of perspective. The hardships of war were genuine; they were very difficult, but also the notions of widespread starvation and things like that – that’s simply not true. Have you ever read an account where someone said ‘X starved to death?’ I’ve never seen one. To be honest I don’t think anyone’s looked at more Civil War soldier letters and diaries than I have.

Everyone I have talked to has mentioned Yael Sternhell’s book, Routes of War, specifically. I find that interesting.

JG: Well it’s very different. She’s from Israel and sees a very different perspective. Those are the exciting things about life! I don’t know if you’ve read reviews of her book – some have been quite critical of it, certain aspects, and frankly, it’s hard to imagine why she would’ve omitted Sherman’s Army, which literally went down the Mississippi River, across to Chattanooga, down to Atlanta, over to Savannah and back up to North Carolina to the end of the war. That’s the ultimate in mobility. [But] she writes beautifully. It’s a book with a great insight.

You’re working for the Civil War Trust. I think a lot of people don’t realize that there’s a pretty significant dissension between what academic historians do and what, say, most non-academic historians do and what the Park Service needs. You’re not going to get tenure at a university writing a battle book. What we’re trying to understand is the human condition as professional historians, and so retracing the conduct and outcome of a battle is not going to contribute in meaningful ways in that area. I’ve read tons and tons of battle books over the years, but nowadays I seldom do unless I need to for research purposes.

My impression is, as far as your career and your work, you are a bona fide military historian though. You say one can’t get tenure with a battle book but your focus has always been strongly on the military aspect.

JG: I am actually trained as a military historian who happens to do a lot of his research and writing in the Civil War period, as opposed to others who are largely trained in the Civil War.

When I took my Civil War & Reconstruction class in college, my professor packed the war itself into one class period. What do you make of that?

JG: Well I teach military history, so I teach the Civil War – I don’t teach a class on the Civil War. I also sometimes teach an undergraduate seminar in the war. So in my military history course we devote quite a number of classes to the Civil War in all facets. I think that’s one of the regrettable things about teaching history, is that there’s not a satisfactory appreciation for military history in general. The Civil War is just one of those examples. Think of all the times people take classes where they skip World War II, the fighting. Sixty million people died in World War II! So the fighting is important. The veterans knew it was important.

Why doesn’t military history get the place you think it deserves in academia?

JG: Part of it has to do with the perception of academic scholars towards battle books, and the way they sell - things like that. Part of it has to do, I think, with naïve notions that studying war promotes war, as if studying slavery promotes enslavement. And I think part of it is – when people go into academe, and this isn’t universal, they’re trying to train young people’s minds; they’re trying to change them. And change is largely more of a characteristic that is associated with liberalism. So academics tend to be a little more liberal. They have greater hopes for change that will improve the country, and so on. They’re not interested in going back – strangely enough especially historians, because we have a better perception of the realities of the past. And so, I think for all those reasons they find the study of military history a little distasteful. There was a lack of innovation, for a while, in military history studies. Nowadays I think it’s much more expansive and creative – it’s better. And the centennial probably drowned out a lot of interest in the Civil War – people were inundated with it. Those are some of the reasons.

How did you decide to become an academic?

JG: I was an undergraduate student at Ohio Wesleyan and I had a phenomenal teacher named Richard W. Smith, who’s still alive – he’s 89. We were on trimester, so one semester in the fall; one semester in the winter and one semester in the spring and in the winter semester I took his Civil War class and I just loved it. Then I approached him about doing a senior thesis, and I wrote that in my spring semester and it was on Grant’s Vicksburg campaign. And I just had a blast with it. At that point I had applied and was admitted to go to law school but during the summer I thought more and more about it and decided that I didn’t want to go to law school – what I really wanted to do was study history. So I went up the hill to visit my friend’s aunt who was visiting, and she’s a pretty famous historian who is now retired at the University of Calgary. Her name is Marion McKenna and she’s written about a dozen books, and she’s a Columbia PhD, a student of Allan Nevins. So I talked to her and she gave me some advice about where to apply, and she and Harold Hyman, who is a very distinguished legal historian and did a lot of work on the Civil War era, were classmates together at Columbia. They also had Frank Vandiver, and so I started reading, and I loved Vandiver’s work, so among the places I applied was Rice, because they had two really amazing Civil War historians. So I went down there. I worked for Frank Vandiver for my masters before he left to accept the presidency of North Texas State University after a personal tragedy. I had been admitted previously to Wisconsin, and they had a great military historian named Edward M. Coffman, so instead I went up and got a PhD there. When I was at Rice, Vandiver recommended I take military history, and I started reading military history with him and I really enjoyed it. So at Wisconsin my specialty was really American military history.

What was the first battlefield you went to?

JG: There was a Revolutionary War battle in White Plains, and I traced that, I remember, as a kid. But of course there’s no real battle field, per se. First Civil War battlefield I don’t remember! It could’ve been Antietam, First Manassas, or Bentonville. Franklin and Nashville I covered for my master’s thesis, I was probably 21 or 22, those would’ve been among my earliest ones.

Do you have a favorite, now?

JG: I don’t know if I have a favorite. Antietam is great, Shiloh is great, Perryville is great because almost no one’s there! I remember being at Perryville with two friends of mine, Coffman actually, and George Herring, a very distinguished foreign policy historian. The three of us just decided to go for a tour; we had a blast, and we were the only people on the whole battlefield. It was a nice day!

I’ve had such great experiences on battlefields. When I worked at the Army War College I would go with Jay Luvaas, and lead tours at Gettysburg. I loved going to the battlefields when Bob Krick was the chief historian at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania. Ed Bearss going through Stones River – so many great battlefield memories. Ed Bearss and I once did a Banks’ Red River Campaign. There are so many great battlefields. We’ve actually done a really great job in the last twenty years of preserving battlefields. I think that’s the single greatest contribution of the last twenty years! We could’ve lost these battlefields. And we did lose a bunch of land, but we did an amazing job in saving them.

That’s a lovely thought – that the single greatest contribution to Civil War scholarship in the last twenty years is actually the preservation of the battlefields.

JG: Well a lot of people don’t realize that if you don’t walk the battlefields, you really can’t get a feel for what these people endured. We’re walking up and down hills at Antietam, on a relatively warm September day. By 3 P.M. we’d be tired and we’d want to lounge around the ground. Civil War soldiers didn’t get that luxury!

The real way to do it would be to march up from Harper’s Ferry that day!

JG: That’s right. Which would actually be fun if we could ever arrange something like that.

What do you make of the sesquicentennial commemorations so far?

JG: I think it’s been a disappointment, don’t you? I just think it’s a matter of resources, and a matter of disorganization. If you go back to 1960, they had a central organization, headed by Bud Robertson. It was a much bigger deal – the centennial than the sesquicentennial. I don’t know why. There’s a conscious effort to shift away from military issues, which strikes me as odd since the war was a war. The fact of the matter is that emancipation was not about to happen without war. The divisions have been a problem, the resources have been a problem. Various groups were lobbying to be designated really early on as the center. We should’ve had a national commission.

Is there anything in Civil War scholarship that you feel demands further scrutiny or hasn’t gotten the attention it deserves?

JG: I think immigrants haven’t gotten the attention they deserve. The problem is that you need somebody who’s interested in going into U.S. history who can read multiple languages. You have to be able to read German – there were a lot of German soldiers in the Union, some Hungarian, some Irish, but there you can read English; Englishmen, some French. You really would want to be able to read multiple languages. Those would be the most prominent. Maybe Spanish if you’re looking at places like Texas.

Is there a particular narrative that you disagree with that won’t go away; that disturbs you because of its prevalence.

JG: Like the ‘rich man’s war and poor man’s fight?’ The statistics don’t bear it out. The bottom line is: wars are hardest on poor people, there’s no question about it, and many people in the military – rich or poor – resented when individuals weren’t serving who were physically capable of doing so. In General Lee’s Army I have statistics about those who got exemptions for twenty slaves or more – and it’s miniscule. Five times as many clergymen got exemptions; five times as many city or state employees got exemptions; four times as many shoemakers got exemptions, and you go on and on. When people are that wealthy, they usually are in their forties or fifties and they have children, and their children were serving.

One of the areas that I’m very interested in these days is more statistical studies. If you look at lots of fields like social science what they’re really doing effectively [is] they’re blending statistics with qualitative evidence. In their case more oral interviews and things like that, but in our case it’s more letters, diaries, official materials. Because I think what’s happened is – we have this penchant for picking and choosing the quotations we want to present the kind of point-of-view that we want, and that cherry-picking results in an unrepresentative presentation of what soldiers were actually doing and feeling. Some things you can’t quantify I don’t think, but other things you can quantify and we can gain better insights into these people.

Another thing that they’re doing very well is - a few states are going through the records carefully, combing them, and trying to ascertain the actual number of people who died. Both Virginia and North Carolina have already determined that previous numbers are over estimates. South Carolina, up to this point, has found the same issue. The traditional counts of dead are too high, which contrasts pretty dramatically with an article written in Civil War History using the 1870 census, with a gargantuan margin for error, and concluded that actually more Civil War soldiers died than we know. The U.S. Army’s records are unbelievably accurate. You’re talking about such a miniscule margin of error with the Union, whereas the Confederate records of course are problematic. That’s why you need these state studies. But what we’re finding with state studies is: our previous assumptions about deaths are too high. Actually what we’re likely to find, and it’s becoming quite clear, is actually fewer soldiers died in the Civil War than we had thought. Soldiers now, not civilians. [The number of civilian dead] we probably will never know, because the number of deaths of contrabands is probably huge.

Which work of yours are you most proud of and why?

JG: The best book I’ve written is General Lee’s Army; the one I’m most proud of is Forged in Battle.

How do you make that distinction?

JG: Forged in Battle came out just before Glory. Up until Glory I think a huge percentage of the American people didn’t even know blacks served in the Civil War. And Glory reached them, and Forged in Battle hit the market at that time, and provided historical credibility for issues that were raised in Glory. I would get all sorts of letters from people trying to locate their ancestors, and it was really lovely how many people wrote me nice notes – that they didn’t know about it and how much they appreciate the book. Then all of a sudden you started to get black reenactment groups; I would see them and they would thank me for the book and how influential it was for them. So I think the book made a difference in a lot of people’s lives and that made me feel really good. But General Lee’s Army is the most historically sophisticated book I’ve done.

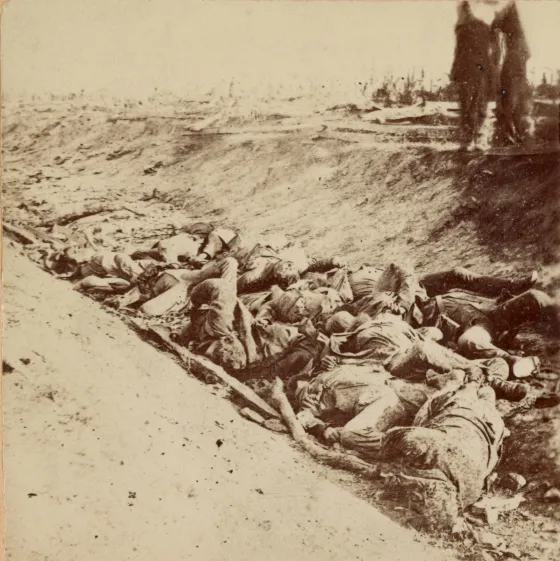

Do you have a favorite Civil War photograph?

JG: I was just involved in a book with Gary Gallagher where they asked me to pick a photograph, and the one I ended up picking is of Sherman with his hair messed up, taken by Mathew Brady, because he looks like a maniac. As a kid it scared the heck out of me; I thought, ‘jeez this Sherman guy is pretty frightening.’ I don’t think I have a favorite photograph. One of my favorites was sent to me – remember I told you about people who read Forged in Battle and contacted me. One of the people was a woman who lives in San Francisco, and she corresponded with me and I helped her get her great-grandfather’s records, and she sent me a photograph of her great-grandfather with his G.A.R. medals, and he was so proud. She also sent me a copy of a letter – he had had a government job, and when the Democrats came to power he got cast out, and then when the Republicans got elected back into the White House, he wrote the president and asked him to get him his old job back! And you just look at that man [in the photograph] and know that service in the Civil War was one of the proudest moments of his life. You could see it on his face. Beautiful photograph.

Why is the Civil War ‘the war that doesn’t go away?’ Why is the Civil War still so compelling?

JG: I think for multiple reasons. The one true democratic republic on planet earth was threatened to be torn asunder, and that is truly dramatic. It’s a war that determines what direction the United States was going and how we would define freedom; who would be free? So we destroyed the institution of slavery. We also had some really interesting characters involved in the Civil War, and I think the fact that we have so much preserved – not just letters and diaries and records at the National Archives (because we had such a literate population) – but the fact that we’ve been able to preserve so many of the battlefields, or at least portions of the battlefield, so that you can continue to go and walk them and get a feel for what these people endured and gain insights into their world. Those are all factors I think.

Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar is the Stephenson Distinguished Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is author of numerous books and articles, including: The March to the Sea and Beyond: Sherman's Troops in the Savannah and Carolinas Campaigns (New York University Press, 1985), Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and Their White Officers (The Free Press, 1989), Partners in Command: Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War (The Free Press, 1994), Forgotten Allies: The Oneida Indians in the American Revolution (Hill & Wang, 2007) with James Kirby Martin, General Lee's Army: From Victory To Defeat (The Free Press, 2008), and Soldiering in the Army of Northern Virginia: A Statistical Portrait of the Troops Who Served under Robert E. Lee (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). He is currently President of the Society for Military History.