The History of Williamsburg

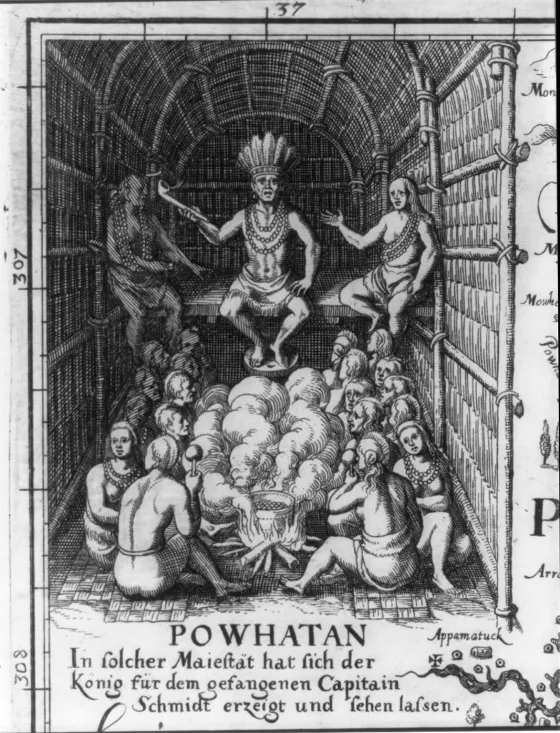

Tsenacomoco and the Powhatan Chiefdom

Long before European colonization, the land bounded by the western fall line and the rivers known today as the Potomac and the James encompassed Tsenacomoco (“densely inhabited place”). Tsenacomoco was the geographic boundary of the political alliance of Indigenous Virginians known as the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. Members of this alliance paid tribute to the Paramount Chief Powhatan (Wahunsonacock). Both the Paspahegh and the Chiskiack, members of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom, shared resources in the area bounded by the Powhatan River, known today as the James River, and the Pamunkey River, known today as the York River. Paramount Chief Powhatan established his capital of Tsenacomoco at Werowocomoco (“place of leadership”) along the Pamunkey River. It was here that John Smith met with the Paramount Chief and his daughter, Pocahontas.

The first permanent European settlement in the region was established by English colonists in 1607 along the river that they renamed the James. Jamestown became the first capital of English Virginia. The relations between the colonists and Indigenous Peoples were not always peaceful. The Anglo-Powhatan Wars of the first half of the 17th century prompted English colonists to fortify their settlements. On February 1, 1632, the General Assembly passed “An act for the Seatinge of the middle Plantation,” which ordered every fortieth man subject to a tithe, or tax to support the church, to take part in the construction of a palisade around “the forrest conteyned between Queenes creeke in Charles river, and Archers Hope creeke in James river.” Two years later, this fortified land situated equidistant from the James and York Rivers, became known as Middle Plantation.

Middle Plantation

Fortified against attack, Middle Plantation became a desirable location for new English colonists to build homes. The rest of the 17th century saw wealthy men moving to the area, eventually shifting political and geographical import further inland and away from the capital at Jamestown. In 1676, colonist Nathaniel Bacon led a rebellion against the colonial government and burned much of Jamestown to the ground, including the statehouse. The capital was destroyed, influential colonists focused their attention on rebuilding not at Jamestown, but in Middle Plantation.

A series of events and decisions influenced the crown’s eventual agreement to move Virginia’s capital from Jamestown to this developing locality. A treaty between Indigenous Virginians and colonial representatives of Charles II was signed at Middle Plantation in 1677 (The Treaty of Middle Plantation). Also in 1677, the vestry of Burton Parish voted to build a brick church at Middle Plantation. In 1693 Virginia’s General Assembly ordered that the new College of William and Mary be built “as neare the church now standing in Middle Plantation…as convenience will permit.”

Establishment of Williamsburg

In 1699, Virginia’s General Assembly officially passed “an Act directing the Building of the Capitoll and the City of Williamsburgh.” The Assembly renamed the locality Williamsburg in honor of King William III, who at that time ruled England and its dominions with his wife, Mary II. Governor Francis Nicholson was instrumental in establishing the capitol and much of what can still be seen today on the city’s main Duke of Gloucester Street, including a capitol building, jail, and other public and private buildings, homes, storefronts, and green space. In 1747 however, the capitol building burnt to the ground, and a smallpox epidemic ravaged the city. For a time the Assembly debated whether to rebuild at Williamsburg or move the capital elsewhere. Ultimately, the decision was made to rebuild. Renewed further and enthusiasm for Williamsburg prompted a wave of building projects and investment in the city.

The Revolution

As the capital city and seat of government, Williamsburg featured prominently in the Virginia colony’s road to revolution. In 1765 the House of Burgesses adopted Patrick Henry’s condemnation of the Stamp Act, and the city saw its own Stamp Act protest on Duke of Gloucester Street. In 1769 residents attended a ball in honor of then-governor Norborne Berkeley, clad in homespun clothing to protest taxes on imported goods.

Perhaps most famously, patriots clashed with colonial governor John Murray, earl of Dunmore. In 1774 Dunmore dissolved the General Assembly after they passed a resolution in support of the city and residents of Boston after that city’s Tea Party protest resulted in Parliament levying the Coercive Acts as punishment. In April 1775, Dunmore ordered the removal of the city’s stores of gunpowder from the powder magazine. Colonists saw this as an outright affront to their protection and liberties and immediately demanded its return. Later that summer Dunmore abandoned the city. With the royal-appointed governor out of the capital, Williamsburg set its sights on supporting the Revolutionary War. The Williamsburg Public Store and its network of the city’s artificers and civilian tradesmen and women supported Virginia’s fighting forces throughout the war.

As the main theater of war moved to the south, Williamsburg became vulnerable to enemy attack. In June 1779, the General Assembly passed “An act for the removal of the seat of government,” citing that Williamsburg was “exposed to the insults and injuries of the publick enemy.” The act passed, and the capital moved inland to Richmond in 1780. Richmond remains the capital of Virginia today. Prior to the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781, important but lesser-known skirmishes took place on the outskirts of Williamsburg as allied patriot troops met loyalists and Cornwallis’ army. At the Battle of Spencer’s Ordinary on June 26, 1781, John Graves Simcoe engaged patriots under Colonel Richard Butler with an inconclusive result. In July 1781 the Battle of Green Springs saw a victory for General Charles Cornwallis and Banastre Tarleton over patriot troops commanded by General Anthony Wayne and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Williamsburg in the 19th Century

After the removal of the seat of the government to Richmond, Williamsburg fell into decline. Even the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary fell into disrepair, and suffered a fire in 1859. Nineteenth-century visitors to Williamsburg noted the town’s sad state, one in 1816 remarked that “Williamsburg seems to be experiencing the fate of all the works of man, except the labors of the mind (and the Pyramids) seem destined to last forever.” Further, one visitor noted that “the whole village bears the marks of poverty.”

While the College continued to function and admit students, perhaps the only noticeable element of the once-burgeoning city center was the Mental Hospital. Now known as Eastern State Hospital, it opened on the edge of town in 1773. The Hospital expanded its footprint in the early decades of the 19th century. By the 1840s, Dr. John Minson Galt II was superintendent of over 125 patients and staff.

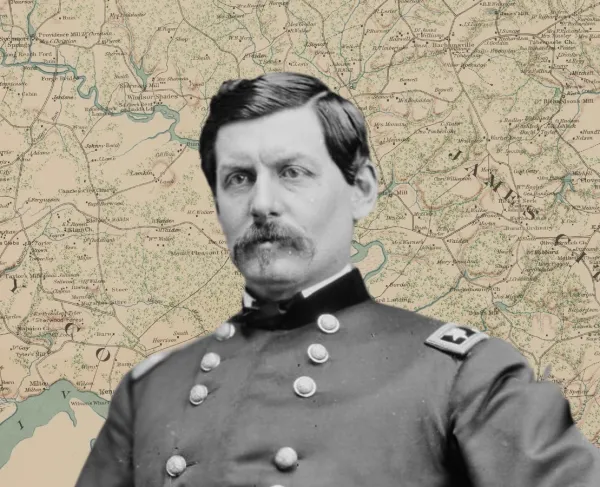

Williamsburg during the Civil War

Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, 1861, and almost immediately Confederates recognized the strategic importance of Williamsburg as the narrowest point on the Peninsula. Confederates impressed enslaved African-Americans to aid in building an elaborate fortified line consisting of fourteen redoubts. The largest of these, Fort Magruder, was named after General John B. Magruder who commanded the Army of the Peninsula.

In early 1862 Union General George B. McClellan intended to march his troops through Williamsburg to advance an attack on Richmond, now the capitol of the Confederacy. The May 5, 1862 Battle of Williamsburg, pitted McClellan against troops commanded by Joseph E. Johnston. This often-overlooked battle, after which both sides claimed uneasy victory, is now seen as a turning point in the Peninsula Campaign, especially for Union troops. Soldiers under Winfield Scott Hancock captured their first Confederate Battle Flag, and Hancock himself received his moniker, “the Superb,” and seven soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor as a result of their actions at Williamsburg.

On the eve of the Civil War, of the nearly 2000 residents of the sleepy former capital, about 750 were enslaved. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued on September 22, 1862, offered confusion and uncertainly in Williamsburg. The Duke of Gloucester Street bisected the town into Confederate-controlled James City County and Union-held territories in York County. This meant that Lincoln’s proclamation effectively freed enslaved people on one side of the street, but not the other. The city of Williamsburg itself was occupied by Union forces for the remainder of the war.

Restoration of the Historic Area

After successful efforts to undertake the restoration of the Bruton Parish Church in 1907, the Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin found benefactors in John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller who shared his vision to restore the remaining historic fabric of the 18th-century town. Beginning in 1924 and throughout the decade, Rockefeller began buying historic homes from their residents in order to establish “a shrine of history and beauty…dedicated to the lives of the nation’s builders.” Today the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation operates the large open-air museum of original 18th-century structures and reconstructed buildings.

Further Reading:

-

Drew Gruber, “The Battle of Williamsburg,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/williamsburg-the-battle-of/

-

Katherine Gruber, “Williamsburg during the Colonial Period,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/williamsburg-during-the-colonial-period/

-

Williamsburg, Virginia: A City Before the State 1699-1999 By: Robert P. Maccubbin, ed.

-

John Salmon, “Tsenacomoco (Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom), Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/tsenacomoco-powhatan-paramount-chiefdom/

-

Williamsburg Before and After: The Rebirth of Virginia’s Colonial Capital By: George Yetter

Related Battles

2,283

1,560

150

75