ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY YEARS AGO the American landscape ran crimson with the spilled blood of its countrymen. The battle smoke of this epic conflict, born out of seemingly irreconcilable philosophical, cultural and economic differences, clouded 10,000 battlefields. Its reverberations were felt in every city, village and hamlet, as a generation of young men marched away to war; even those who returned physically unscathed were forever changed by their experience in the ranks.

As we mark this anniversary, we are offered a unique opportunity to reflect on the origins and ongoing goals of the battlefield preservation movement. While we must recognize that each site under siege by the forces of our modern age faces unique challenges, we can, nonetheless, identify themes and trends among these situations. And in doing so, we can create a roadmap for the work that remains to be done during this anniversary period.

Efforts to commemorate the conflict, and those who fought in it, began almost immediately. The acquisition of land for such purposes was particularly swift at Gettysburg, where a local attorney began purchasing land within months of the battle, and a formal memorial association was founded in April 1864, well before the war’s final outcome was decided. Returning Union soldiers dedicated a monument on Henry Hill at First Manassas in 1865. Memorials to those local residents who answered the call to service sprang up on countless town squares. Sometimes-elaborate monuments were dedicated in the national cemeteries established by Congress to serve as final resting places for the war’s unprecedented number of casualties.

This land … is consecrated with the blood of Americans. Many are still buried here and known only to God. We owe these Americans the right to keep this battlefield preserved for history.

Congressman Ted Poe of Texas

These early preservation and commemoration initiatives were largely driven by the veterans themselves, but the cause gained a significant boost in public support at the time of the war’s 25th anniversary. The young men of the 1860s were now the established leaders of their communities and were driven by a sincere desire to honor their fallen comrades and generate a sense of national unity. Inspired by contemporaneous efforts to set aside the majestic landscapes of the west as national parks, these veterans began advocating for similar treatment of the Civil War’s most significant battlefields. Their work came to fruition in 1890 with the establishment of the first national military park at Chickamauga and Chattanooga; congressional debate on the bill lasted less than 30 minutes in each chamber.

Other major battlefields soon followed suit in gaining legislative protective measures, and by the end of the decade Shiloh, Gettysburg and Vicksburg also received formalized federal status. These initiatives were driven by a variety of factors, notably political considerations, rather than a comprehensive preservation vision — it is notable that only one of the first five military parks represented a Confederate victory and that the language used in creating them varied widely. Immense popular and political support for the Chickamauga effort prompted legislators to provide for up to 7,600 acres of preserved battlefield, along with well-defined missions related to landscape protection and maintenance. Antietam, meanwhile, was set aside with a single sentence added to an appropriations bill just 11 days later.

The marked contrast was spurred, in part, by the common perception that because so much of the Gettysburg Battlefield had already been protected by private entities, significant efforts at nearby Antietam — although the bloodiest day of the war and with vast strategic significance and legacy — were redundant and unnecessary. This attitude is further born out in the fact that beyond the begrudging addition of Antietam, each site represented a single major strategic initiative or army, a pattern continued with the addition of the next battlefield park — Kennesaw Mountain, chosen to represent the struggles for Atlanta, Ga. — in 1917.

We have found one another again as brothers and comrades, in arms, enemies no longer, generous friends rather, our battles long past, the quarrel forgotten — except that we shall not forget the splendid valor, the manly devotion of the men then arrayed against one another, now grasping hand and smiling into each other’s eyes.

President Woodrow Wilson, 1913 Gettysburg Reunion

At their inception, these sites were, like the national cemeteries that often preceded them, administered by the U.S. War Department; but they — and all subsequent battlefield parks — would be transferred to the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service in 1933. Officials with the fledgling Park Service had expressed a desire to “be concerned with all areas the Federal Government wishes to preserve and protect for the education, interest and enjoyment of the population” as early as 1915. Three legislative attempts to facilitate the transfer failed before President Franklin Roosevelt completed the transaction by signing an executive order in June 1933. A general lull in park establishment came to an end as the 75th anniversary of the Civil War approached and age claimed an increasing number of veterans with each passing season. A number of new national and state battlefield parks were created during this time, among them: Fort Pulaski National Monument in 1924, Petersburg National Battlefield in 1926, Stones River National Battlefield in 1927, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park in 1927, Fort Donelson National Battlefield in 1928, Virginia’s Sailor’s Creek State Park in 1934, Appomattox Court House National Historical Park in 1935, Richmond National Battlefield Park in 1936 and Kentucky’s Perryville State Historic Site in 1936. This era also saw many battlefield parks and historic sites receiving the rehabilitation attentions of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The remainder of the 20th century saw continued emphasis on setting aside these hallowed grounds, albeit often imperfectly. Waves of activity emerged during the World War II-era, when the bravery and sacrifice of the military were at the forefront of the national consciousness, leading to the establishment of Manassas National Battlefield in 1940 and Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in 1944. Following World War II, the U.S. Army determined that many historic fortifications, like Charleston’s Fort Sumter and the various defenses of Washington, D.C., had passed their prime as military installations, and turned them over to the National Park Service. The War’s centennial coincided with efforts to establish Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield in 1960 and the Virginia Military Institute’s New Market Battlefield State Historical Park in 1967.

Those places that we cherish had better be defended; because development is so swift, so efficient and rather final.

Sam Waterston, Actor

The resurgence in battlefield preservation that began in the last decades of the century was driven by a much different force than its predecessors. No veterans sought to mark the places where their comrades had fallen; no wartime culture motivated remembrance; no major anniversary prompted study. This generation of preservation began as a reaction to rampant unchecked growth — development that appeared like the proverbial barbarians at the gates of existing parks or threatened to overwhelm sites not set aside by previous preservation-minded generations of legislators and officials.

In 1987, alarmed at the wanton destruction of the battlefields in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., a group of historians and activists formed the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites. Their act changed the very nature of battlefield preservation, taking it from solely the realm and mission of government bodies and providing individual Americans with the opportunity to contribute and make a tangible difference in decisions regarding the future of this hallowed ground. While groups focusing on the protection of a particular battlefield had existed previously, for the first time a single entity would pursue a holistic approach to preservation, spreading its attentions across the map. It is from these efforts that the modern battlefield preservation movement and the Civil War Trust as an organization trace their beginnings.

The groundbreaking work of the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission also had its genesis in this time of realization that a historic pedigree was not enough to forestall the threat of loss. After the federal government was forced into a legislative taking to prevent the construction of a 1.2-million-square-foot regional shopping mall, office and residential park on a 550-acre portion of the Manassas Battlefield, Congress issued a call for a study to investigate the state of our Civil War battlefields. These findings, which include assessments of both historic significance and preservation status, form the backbone of current land protection strategy.

We too are part of history. And we are going to be judged by history, just as those who came before us … and how will they judge us on this issue?

David McCullough, Historian

If past patterns are any guide, the current sesquicentennial commemoration will initiate another era of renewed enthusiasm for the cause of battlefield preservation. The infrastructure and record of success amassed in the past two and a half decades — 30,000 acres protected through public-private partnerships, a figure that eclipses the total land area protected in aggregate by the federal government until that time — represent a groundwork laid for tremendous success.

Yet, even as we begin to build upon our past victories, capitalizing on this time of increased public interest, we recognize that there is much work to be done if we are to secure a legacy of adequate protection for these priceless resources. While the situation at each battlefield or historic site is unique, there are several distinct themes that emerge upon examination of the situation in which the preservation movement finds itself at the dawn of the sesquicentennial. Here we profile some of these key challenges, using examples of both the threat and situations in which it is being successfully combated.

Infrastructure for Growing Communities

I urge [local] decision makers to plan … carefully. The choices they make will be felt for generations to come, making this the time to be thoughtful and deliberate, not rash.

Robert Duvall, Actor

IN ECONOMIC TIMES such as these, there are fewer proposals to dot the land with sprawling suburban subdivisions than there were just a few years ago. This does not mean that such development has halted entirely, but its decline allows for greater community emphasis on infrastructure enhancement to keep pace with the recent spate of unprecedented growth. From improving cell phone coverage or ensuring a reliable supply of electricity to easing congestion on clogged roads, such projects could provide a great benefit to residents. But at what cost?

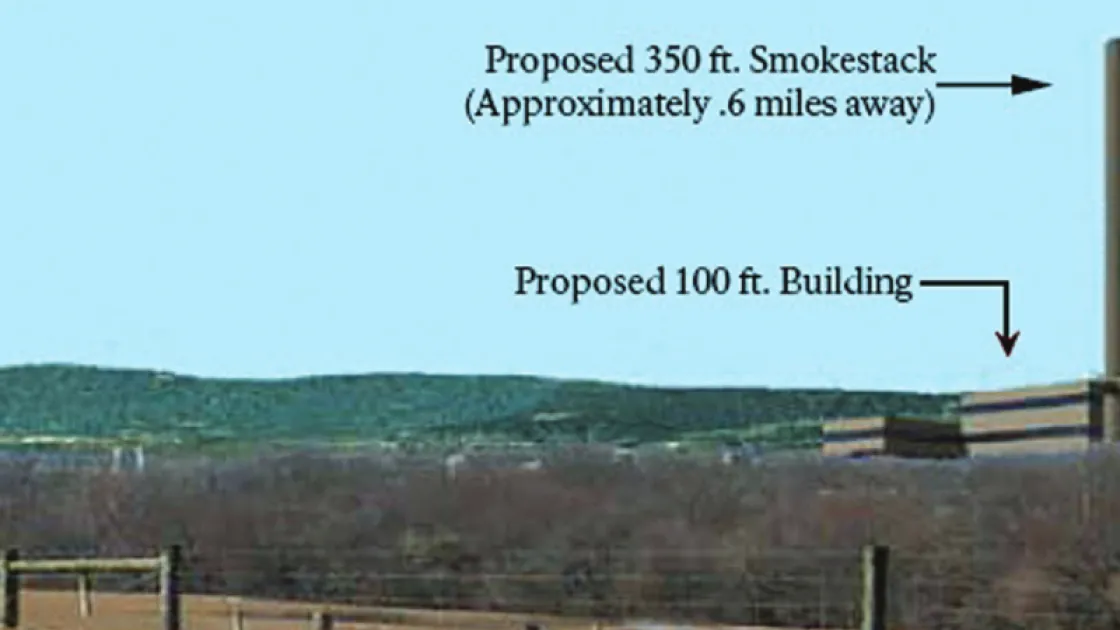

Fought just south of Frederick, Md., the July 1864 Battle of Monocacy is often referred to as the battle that saved Washington. Legislation to establish a national battlefield at the site was passed in 1934, but no land was acquired by the Park Service until 1976. Already bisected by Interstate 270, a major regional commuter artery, the battlefield may soon have another unwelcome neighbor — a waste-to-energy facility, or, put more simply, a trash incinerator. Despite consistent public and political opposition to the plan, in late May 2011, the Frederick County Board of Supervisors voted to continue with permitting procedures to build the facility on the banks of the Monocacy River, immediately opposite the battlefield. Their position was bolstered earlier in the month when Maryland’s governor signed a bill that classifies incinerators as renewable energy suppliers, making them eligible for attractive tax incentives.

Nor is this a lone example. Elsewhere in the Old Line State, a power company has purchased land on the South Mountain Battlefield and is considering it for a natural gas compression station. A “wind farm” is poised to tower over the landscape of the Camp Allegheny Battlefield on the Virginia –West Virginia border, despite numerous regulatory and financing delays. The Third Winchester Battlefield is just the latest site to see a proposal for a looming cell tower.

When considering the impact of such projects, it is important to remember and emphasize that preservation is not inherently anti-development; it is merely pro-smart development. Often, battles were waged over control of population centers, road junctions, ports or other hubs of human activity that are still vital aspects of modern life. Communities must grow and evolve; they cannot remain frozen in time. But as local governments contemplate where and how to meet these needs, consideration should always be given to historic resources. A battlefield cannot be moved, but perhaps an alternate site can be found for this planned endeavor? In the case of road expansions — like those currently being considered at Brandy Station, site of the war’s largest cavalry engagement — could strategic spot improvements be utilized over a blanket widening?

Inside History, Outside the Park

In the heat of battle, no unseen hand kept soldiers inside what would one day be a national park. Such boundaries are artificial, modern constructions shaped by external factors, and have little bearing on what is or is not historic.

James McPherson, Historian

ACCORDING TO THE Department of the Interior’s American Battlefield Protection Program, 20 percent of the area over which the war was fought has been permanently lost, paved over or otherwise eliminated. Another 20 percent is permanently protected, whether by a national, state or local park, or recognized conservation entity, like the Civil War Trust and its partners. The fate of the remaining 60 percent hangs in the balance.

Certainly, some of this land is at battlefields where no formal park or preserve has ever been established. Often, however, the most visible and wrenching threats involve development proposed for the fringes of a well-known battlefield, on land that experts universally agree is historic and ought to be treated with sensitivity but is, nonetheless, outside the current administrative boundaries of the park. Illustrations of this scenario abound, from Disney at Manassas in the early 1990s to two unsuccessful proposals to bring casino gambling to Gettysburg in the last five years.

Outcry over such well-publicized cases may be enough for a developer to reconsider. In early 2011, Walmart chose to “do the right thing” and abandon plans to build on a site historian James McPherson declared stood at the “nerve center” of the Union army during the Battle of the Wilderness. But not all such situations end happily. At Cedar Creek, a limestone mine has received all necessary approvals to expand its operations onto one of the battlefield’s most historic areas, where rallying Union troops counterattacked and turned the tide of battle.

How is it that we come to arrive at such impassioned impasses? Virtually no Civil War battlefield has been protected in full; politics have always played a role in determining their extent and array. The earliest private land preservation efforts were at Gettysburg and Antietam, Northern sites where residents and politicians were concerned with honoring “their heroes,” the Union soldiers. Not until the authorization of Chickamauga in 1890 was there any formalized mandate to protect any lands associated with a Confederate position.

When park boundaries were drawn in generations past, there was no possible way to predict the growth experienced by our nation in the latter decades of the 20th century. Individuals who could not conceptualize our present strip malls and mega-highways had no reason to imagine that rural landscapes would be transformed; a family farm, they assumed, even if sold to a new owner, would always be a family farm. Moreover, since parkland is nearly always acquired from willing sellers, indisputably historic properties have eventually become completely encircled by protected areas and are known as inholdings.

All of these are issues that have been present since the establishment of parks and preserves, and we continue to correct for them today. In all such instances these efforts can be hampered by the underlying zoning of these proximate areas. For example, the fact that the Slaughter Pen Farm, contiguous to the national park at Fredericksburg but outside its authorized boundary, was zoned industrial drove the purchase price paid by the Civil War Trust in 2006 to an astronomical $12 million. Permissive zoning that includes a broad definition of “mixed use” development in Adams County, Pa., home of the Gettysburg Battlefield could allow anything from small businesses to amusement parks right up to the edge of the park.

In places where development already exists, preservation opponents may claim that the damage has been done and more construction should go unquestioned and unchecked. This philosophy, however, only condones and exacerbates the problem and contradicts the long standing pattern of removing such ill-considered experiments. The amusement park that stood on Little Round Top in the 1880s was dismantled before the turn of the century; the motels that once lined the Emmitsburg Road in the vicinity of Pickett’s Charge were removed by the generation before ours. For us to fall into such a pattern of development escalation is to regress in our thinking.

Islands in the Sea of Sprawl

The difference between a battle that is written about and taught to our children and one that is largely forgotten can be summed up in one word — preservation.

- Trace Adkins, Musician

A CENTRAL QUESTION for the evaluation of preservation strategy at the sesquicentennial is how to determine what remaining land should be protected since, with an average of 30 acres lost per day, we must act swiftly and decisively. Since protecting every remaining acre is financially infeasible and logistically impractical, reflection must be given to what properties are most crucial. While every historic site has its own unique attributes and intrinsic value, an appropriate barometer is to consider what landscapes will be vital for scholars of the next century to gain a full understanding of the war.

Often, this translates into filling in the gaps at a battlefield where patches of critical land have been set aside, but they are not enough to tell the story of what happened on that site and the surrounding landscape. Correcting this situation can be particularly rewarding, as at Glendale, where the Civil War Trust has, in the words of historian Robert Krick, “preserved a major battlefield virtually from scratch.” The transformation from a single acre preserved as a national cemetery to a true interpretive destination has been dramatic. But even in this instance, preservation is more a matter of reaching a critical mass than of total completion.

Sadly, such a nearly miraculous transformation is often all but impossible. The destruction of the Chantilly Battlefield — today reduced to the 4.8-acre Ox Hill Battlefield Park in place of the 300-acre combat area — was the direct impetus for the modern preservation movement. Near Atlanta, 14.5 acres inside Tanyard Creek Park is all that remains of the bloody Battle of the Peachtree Creek. Minor portions of the Williamsburg Battlefield have been protected, but development — some of it decades old and built to support the heritage tourism industry surrounding the region’s more well-known colonial pedigree — has already destroyed a great deal. Nonetheless, in 2010, the Trust had the opportunity to secure an undisturbed one-acre parcel and jumped at the chance. Likewise, at just one acre, Tupelo National Battlefield is the smallest battlefield unit of the National Park Service, but in 2009, the Trust was able to help the Brices Crossroads National Battlefield Commission, which administers another nearby park site, purchase 12 acres of historic land well outside the current federal boundary.

The process may come more often in small acquisitions — a handful of acres at a time rather than vast swaths of land — but steady progress can be made with persistence and conviction. Take, for example, the case of Franklin, Tenn., where, parcel by parcel, a determined local organization is reclaiming battlefield land that conventional wisdom would deem lost forever. By purchasing fast food restaurants and strip malls, removing modern structures and returning the land to its wartime appearance, they are encouraging tourism and scholarship, allowing the battle to earn a more appropriate level of public recognition.

In the case of national parks, it should be noted that variations in the language establishing each site can create further complications in this process. For some battlefields, Congress outlined specific properties that may become part of the park in the future, should the opportunity to acquire them arise; other sites were given an acreage ceiling not to be exceeded. As we have seen, however, neither tactic guarantees that critical, blood-soaked hallowed ground is not inadvertently excluded, and altering these administrative boundaries typically requires an act of Congress. At present, legislation is under consideration to adjust the boundaries of Petersburg National Battlefield and Vicksburg National Military Park to allow for present preservation initiatives. Consideration is also being given to the establishment of a national park unit at Fort Monroe, with meaningful conversations about the extent of protection-suited lands — a level of discourse not present for the establishment of some of the earliest parks.

Seeking Authenticity of Experience

The Civil War was our bloodiest conflict but also the densest concentration of courage ever shown on this continent. America’s Civil War battlefields are where that courage is best memorialized. Let’s keep them, and keep them glorious and beautiful.

Ben Stein, Economist

AT ITS MOST BASIC, battlefield preservation is about securing historic landscapes such that they are forever removed from the threat of inappropriate development. But in doing so, we have a larger responsibility to ensure that these sites are accessible to the public so that all may walk these landscapes to gain a greater depth of understanding than what is available in even the finest book or documentary. Properly protected, maintained and interpreted, a battlefield is an outdoor classroom, where students of all ages can follow in the footsteps of heroes, the ultimate goal of preservation.

Enabling this type of experience requires that public visitation is allowed and that measures have been put into place for guests to learn independently from the site. The erection of markers on battlefields is nothing new; the first five military parks — Antietam, Chickamauga, Gettysburg, Shiloh and Vicksburg — saw nearly 5,200 sculptures, tablets and monuments placed at significant spots during their first decades, often designed, placed and dedicated by veterans groups. Highly symbolic and installed piecemeal, these items more closely resemble commemorative public sculpture than educational resource.

Modern efforts follow a different route, seeking to provide visitors with an authentic, informative experience. Where possible, landscape restoration is practiced, allowing for wooded areas to be thinned, fences rebuilt and orchards replanted, as appropriate. The results of such efforts can be dramatic and vastly improve scholarly understanding of how an engagement unfolded, such as at the Deep Cut at Second Manassas. The overarching goal is to give visitors a glimpse into the past, letting them see the battlefield in a condition as close to what participants experienced as possible. Interpretation is a key tactic for helping casual and independent visitors gain a full understanding of a site’s historic significance, one that the Trust has successfully employed at Spring Hill, Third Winchester and others. Physical signs are designed to be unobtrusive in their effort to impart information, and through the Trust’s new Battle App initiative, we have the ability to employ smart phones to make them virtual, multimedia presentations.

Today, in the face of budget and staff cuts, many historic sites have been forced to reduce hours and historian-led programs. Other sites face unique and often costly challenges predicated by quirks of their location. Physical damage resulting from natural forces — such as the hurricane strikes that have repeatedly shuttered Louisiana’s Fort Pike, the tornado that struck Stones River National Battlefield in 2010 or the recent flooding and erosion at Port Gibson, Miss. — take a significant toll. Urban historic sites, like Fort Stevens and the other Defenses of Washington are surrounded by incompatible development and face near constant inappropriate recreational use.