The Fort Gower Resolves

The months before the first shots of the Revolution were full of resolutions and declarations, but only one of them was made by men in arms. The leaders of a victorious militia army, full of bravado on their way back from the frontier, made a statement that was hard to ignore. Like the other declarations, it insisted on American rights while professing continued loyalty to the King. That loyalty was clearly conditional, however, making the document read like a not-so-veiled military threat.

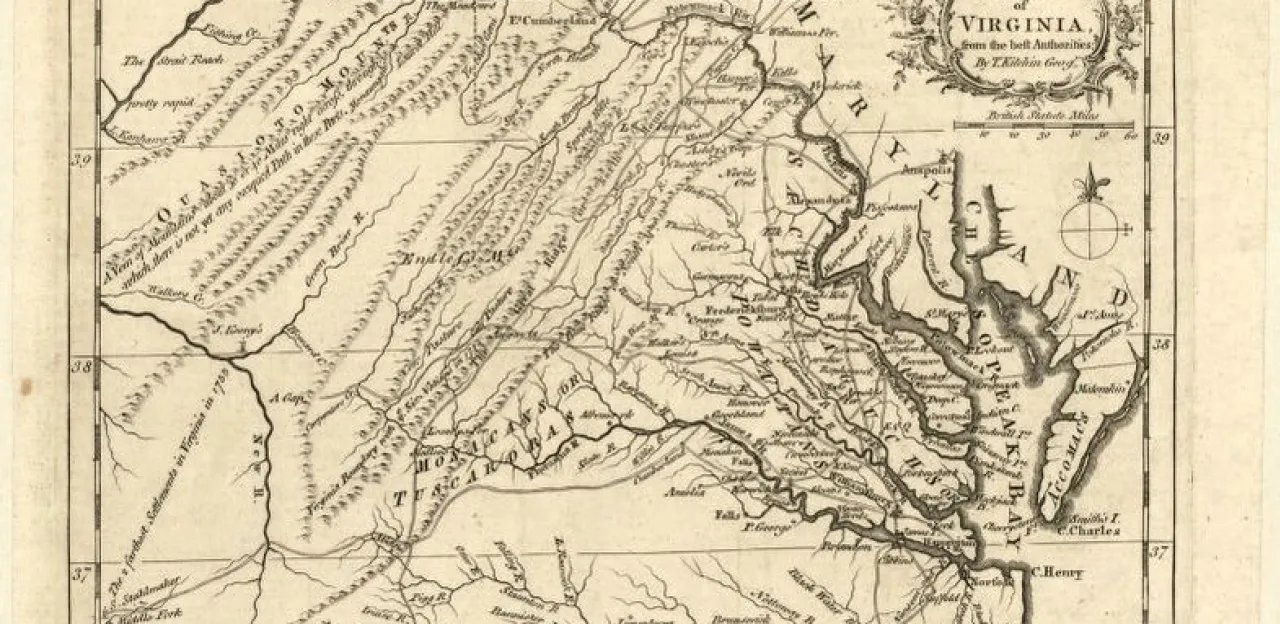

Virginia, Britain’s oldest and biggest American colony, had charter territory reaching all the way to the Mississippi. While the colony made a genuine effort to respect Indian rights by barring western settlement on land not acquired by treaty, individual settlers ignored these restraints. In 1768, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix extended the settlement line to the Ohio River and opened what are now Kentucky and trans-Appalachian West Virginia to settlement. The treaty was made with the Iroquois, who claimed authority over the region. However, the tribes who actually lived there objected and in 1774 that lead to war.

Tensions were also starting to boil over between the colonies and the Great Britain. Most Americans strongly objected to Parliament’s levying of “internal” taxes on the colonies because they had no elected representation in London. Parliament clamped down hard on Massachusetts after the Boston Tea Party by blockading Boston Harbor and taking other measures. In Williamsburg, Virginia’s House of Burgesses responded by declaring June 1, 1774 a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer. The Old Dominion’s governor, the Earl of Dunmore, dismissed the legislature. The Burgesses then met at a tavern, where they proposed a non-importation policy against British goods (the word “boycott” did not yet exist), proposed the First Continental Congress, and scheduled the first extralegal Virginia Convention for August 1. The intervening two months were to allow delegates "an Opportunity of collecting their sense of their respective Counties."

Dozens of Virginia’s counties convened public meetings that produced resolves and resolutions to state their positions and instruct their delegates. They invariably proclaimed loyalty to the King while accusing Parliament of violating the British Constitution, their colonial charters, and universal principles of just government. The Fairfax County Resolves, for example, asserted that the core of the British Constitution was “the fundamental Principle of the People's being governed by no Laws, to which they have not given their Consent.” A distinction was made between Parliament and George III. Though Parliament did not represent them, the King was different. As sovereign, he was the representative and protector of all his subjects. The colonial charters had been granted by previous kings, not by Parliament. The colonists hoped, or pretended to hope, that George III would take their side.

For the time being it was Lord Dunmore who was Virginia’s champion. In July, he headed west to personally lead a war against the raging Shawnee and Mingo tribes who were killing settlers to stop Virginia’s western expansion. The Shawnee, who referred to Virginians as the “Long Knives,” lived on the north side of the Ohio River but hunted on the south side—the side that had been sold to Virginia by the Iroquois. Subordinate to the Iroquois since the Beaver Wars of the 17th century, the Shawnee had not had a meaningful voice at Fort Stanwix. The Mingo were mostly former Seneca who had broken away from the Iroquois Confederation. Despite that heritage and having no separate claim of their own to the territory, the Mingo also ignored the treaty. Word spread along the south bank of the Ohio that “the Shawnese intended to rob the Pensylvainans & kill the Virginians where ever they could meet with them.” Unauthorized acts of violence went both ways, some of them exceptionally brutal. Dunmore’s army approached the Native army in two divisions: a northern division, led by Dunmore, and a southern division, led by Col. Andrew Lewis. Dunmore’s division traveled down the Ohio from Fort Pitt while Lewis’s division traveled north (downstream) on the Kanawha River through what is now West Virginia. The governor halted at the Hockhocking River (now the Hocking River), expecting to rendezvous with Lewis. On October 10, the southern division met an Indian army at Point Pleasant and engaged in a day-long battle.

The First Virginia Convention convened in Williamsburg while Dunmore was gone. It formed an “Association,” pledging to suspend trade with Great Britain, to make the colony more economically self-sufficient, and to provide material support to the people of Boston. Though not intended as revolutionary—Dunmore was still popular—the Convention and the Association gave teeth to the recommendations that had been made in June. The Convention also appointed Patrick Henry, George Washington and five others as delegates to the First Continental Congress. When the Congress convened in Philadelphia in September, it formed a Continental Association, similar to Virginia’s, to stop trade with Britain. It also urged the counties of each colony to form committees to enforce the embargo.

The Virginians suffered more than two hundred killed and wounded at Point Pleasant, but won the day. Precise Indian casualties are not known. Dunmore, who may have heard the gunfire from Fort Gower, united his two divisions and negotiated terms with the Shawnee at Camp Charlotte near the Shawnee towns. The Mingo refused to negotiate. The victorious Dunmore assigned garrisons to Point Pleasant and other key locations before dismissing the rest of his army and heading back to Williamsburg.

Many of Dunmore’s officers convened at Fort Gower to draft and adopt a statement before leaving. The setting suggests the officers were mostly or entirely from the northern division, but no list of names or signatures survives. What prompted them to draft the resolution then and there is not clear. A response to news from Philadelphia (the Continental Congress) or from Boston (the Massachusetts Powder Alarm) is ruled out by the text of the declaration itself. They may have done it because the Indian war had prevented most of their counties, western ones, from producing resolutions that summer. Though Augusta, Berkeley, Botetourt, and Fincastle counties would issue resolutions soon, the assembled officers may simply have been eager to express themselves.

The Fort Gower Resolves were reported in the December 22 issue of Dixon and Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, published at Williamsburg. It had two parts: a report on proceedings followed by the resolves themselves. There are clues in the text to the officers’ motivation and to the document’s intended effects. An officer’s address, usually attributed to Col. Adam Stephen (the senior officer of the northern division), asserted that they were men to be feared: men who could live in the wilderness for months without supply or shelter and still be victorious. This “respectable Body” was ready at all times to fight for Virginia’s “just rights and privileges.” Yet, they would exercise restraint. They would not allow their military power to be coopted by “designing Men” and would reserve it for “no Purpose but for the Honour and Advantage of America in general, and of Virginia in particular.”

In the first resolve, they promised to “bear the most faithful Allegiance to his Majesty King George III, whilst his Majesty delights to reign over a brave and free People.” This implied that the converse was also true. They would defend the “just Rights and Privileges” of America, “not in any precipitate, riotous, or tumultous Manner, but when regularly called forth by the unanimous Voice of our Countrymen.” Congress or the Virginia Convention had only to say the word.

The second of the two resolves unambiguously lauded Lord Dunmore for his leadership of the campaign. The governor had, in fact, acted squarely in the interest of the colony, opening up a huge area for settlement and land speculation. Moreover, he had risked his standing with the Crown to do it. This illustrates the short window of time when, though men had dug in their heels and war was probably inevitable, people’s relationships and willingness to extend congratulations did not yet reflect the new reality. Seven months later, Dunmore was compelled to flee from Williamsburg.

At a Meeting of the Officers under the Command of his Excellency the Right Honourable the EARL of DUNMORE, convened at Fort Gower, November 5, 1774, for the Purpose of considering the Grievances of BRITISH AMERICA, an Officer present addressed the Meeting in the following Words: “GENTLEMEN: Having now concluded the Campaign, by the Assistance of Providence, with Honour and Advantage to the Colony, and ourselves, it only remains that we should give our Country the strongest Assurance that we are ready, at all Times, to the utmost of our Power, to maintain and defend her just Rights and Privileges. We have lived about three Months in the Woods, without any intelligence from Boston, or from the Delegates at Philadelphia. It is possible, from the groundless Reports of designing Men, that our Countrymen may be jealous of the Use such a Body would make of Arms in their Hands at this critical Juncture. That we are a respectable Body is certain, when it is considered that we can live Weeks without Bread or Salt, that we can sleep in the open Air without any Covering but that of the Canopy of Heaven, and that our Men can march and shoot with any in the known World. Blessed with these Talents, let us solemnly engage to one another, and our Country in particular, that we will use them to no Purpose but for the Honour and Advantage of America in general, and of Virginia in particular. It behooves us then, for the Satisfaction of our Country, that we should give them our real Sentiments, by Way of Resolves, at this very alarming Crisis.”

Whereupon the Meeting made Choice of a Committee to draw up and prepare Resolves for their Consideration, who immediately withdrew; and after some Time spent therein, reported, that they had agreed to, and prepared the following Resolves, which were read, maturely considered, and agreed to nemine contradicente, by the Meeting, and ordered to be published in the Virginia Gazette:

Resolved, that we will bear the most faithful Allegiance to his Majesty King George III, whilst his Majesty delights to reign over a brave and free People; that we will, at the Expense of Life, and every Thing dear and valuable, exert ourselves in Support of the Honour of his Crown and the Dignity of the British empire. But as the Love of Liberty, and Attachment to the real Interests and just Rights of America outweigh every other Consideration, we resolve that we will exert every Power within us for the Defence of American Liberty, and for the Support of her just Rights and Privileges; not in any precipitate, riotous, or tumultous Manner, but when regularly called forth by the unanimous Voice of our Countrymen. Resolved, that we entertain the greatest Respect for his Excellency the Right Honourable Lord Dunmore, who commanded the Expedition against the Shawanese; and who, we are confident, underwent the great Fatigue of this singular Campaign from no other Motive than the true Interest of this Country.

Signed by Order, and in Behalf of the whole corps,

BENJAMIN ASHBY, Clerk.

Recommended Reading:

The Dunmore and Frederick Resolves, June 1774.

The Fairfax County Resolves, July 18, 1774.

Jim Glanville, “The Fincastle Resolutions,” The Smithfield Review vol. 14 (2010), pp.69-119.

Harry M. Ward, Adam Stephen and the Cause of American Liberty (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989).

Glenn F. Williams, Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era (Yardley: Westholme, 2017)