“The Exercise of a Little Skill”

“I trust General Grant will sustain his former reputation,” wrote Emory Upton to his sister, “and administer to General Lee such heavy blows that he may never recover.” On the day he wrote that letter, April 10, 1864, it is unlikely that Colonel Upton could have fully anticipated the weight of those “heavy blows.” Two months later, after five weeks of active campaigning and severe fighting, the Army of the Potomac had lost a staggering 49,400 men in four major battles. Just after Cold Harbor, in which his brigade had been heavily engaged, Upton again wrote his sister that he was “disgusted with the generalship displayed” during the campaign. “Thousands of lives might have been spared,” he griped, “by the exercise of a little skill.”

In the west, matters were quite different. During those same five weeks (May 4 to June 12), the Military Division of the Mississippi, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s command, had lost scarcely more than 8,500 men—less than 20 percent of Grant’s loss in the Virginia. While his friend seemed to be wielding the Army of the Potomac like a blunt instrument, Sherman nimbly maneuvered his armies around his enemy’s flanks, turning tactical defeats into strategic advantages.

That Sherman managed to retain the strategic initiative while preserving his army cannot be overstated. While one of Sherman’s men wrote that they were “seeing pretty hard times,” the attitude of men in the west did not approach the dejection felt by those in the Army of the Potomac. The short, sharp fights waged by Sherman, while no less deadly or trying, did not have the same demoralizing effect of Grant’s massive assaults and lengthy casualty lists. Why was there such a great disparity between the Union losses in the East and West? Was Sherman exercising the “little skill” that Upton craved?

Examining the organizations in the East and West provides some clues. Sherman had inherited an army group that had already been groomed for the kind of maneuver warfare their commander intended to wage in Georgia. One of its component armies, the Army of the Tennessee, had experienced it firsthand during the Vicksburg campaign when it marched 175 miles through the Mississippi countryside, drawing the Confederates out of their works and beating them in the open field at Raymond and Champion Hill. In addition, the majority of Sherman’s subordinates were an aggressive bunch, not averse to taking the initiative and pushing an attack through. Even the hard-luck Army of the Cumberland—by far Sherman’s largest and slowest element—had its fair share of aggressive general officers, most notably Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, whose Twentieth Corps brought some eastern theater élan to the rugged western army. In other words, Sherman commanded a body of troops that had been largely molded to his purposes, commanded by an aggressive set of generals. They were well-practiced in rugged terrain and accustomed to victory.

Grant, on the other hand, had no such luck. Hard lessons from Lee and Jackson had taught eastern generals to be cautious, even fearful, of their adversaries. Under the close scrutiny of President Lincoln and other politicos in Washington, prudence often turned to a sort of paralysis on the battlefield that was wholly incompatible with Grant’s aggressive style of warfare. Grant’s position as General-in-Chief created additional awkwardness with Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade—an arrangement that greatly hindered Grant’s ability to shape the army to his will. The Federals, for instance, might have caught Lee off-guard with a swift punch in the Wilderness on the morning of May 5—had Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren not delayed. Instead, it took three hours for Grant to get Meade to order Warren to attack. By then, the Confederates were entrenched and a bloodbath ensued.

Had the eastern troops had been coddled by over cautious leaders to the point where they lost their aggressive spirit? Grant seemed determined to find out, sending them forward in massive assaults that he largely believed could have succeeded if his men—or, more accurately, his generals—put their backs into the work. In doing so, he vastly underestimated Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. It would take time for Grant to temper his frustration with the army under his command with a healthy respect for his adversary. Until he did, however, the Ohioan’s aggressive tendencies would continue to create more and more casualties.

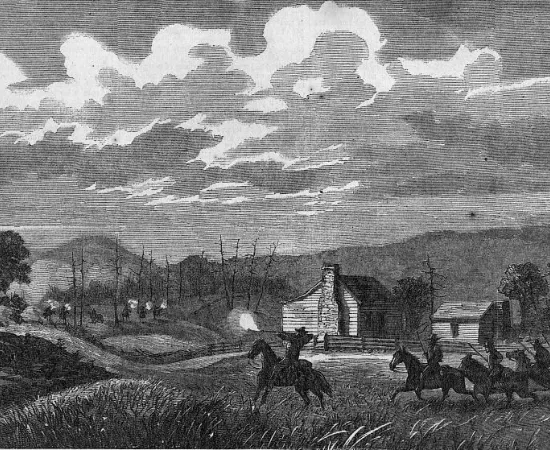

For his part, Sherman had a great deal of respect for his opponent, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and, more importantly, for the formidable earthworks the Confederates erected throughout the campaign. This revealed the way in which terrain also played a role in shaping the two campaigns. Even if Sherman had wanted to throw his entire force at Johnston’s earthworks (which he did not) the rugged, mountainous North Georgia countryside made it nearly impossible for him to attempt the kind of large-scale assaults that Grant was making in Virginia.

The farm country of Virginia was much easier by comparison and therefore much more conducive to offensive operations. However, this worked against Grant as much as it worked in his favor. If properly led and coordinated, his troops could have advanced swiftly over the ground at Laurel Hill, for instance, but that same open terrain gave the Confederates open fields of fire, leading to heavy losses.

The numerical disparity between the losses in Virginia and Georgia was ultimately the result of a combination of these factors. Grant—a commander in a new theater of war, leading an army unfamiliar with him (and he with it), and facing an aggressive opponent with whom he had no previous experience—was bound to struggle while he worked to understand his new environment. Sherman—who was familiar with both his army and the area of operations through which he would lead it—seemed very likely to succeed against a general as cautious as Joe Johnston.

This leads us to the other factor contributing to the differences between the East and West in May of 1864, the Confederate commanders…

Related Battles

17,000

13,000