Duke Against Augusta

Nestled along the river plain forty-three miles above Cincinnati sits the idyllic Ohio River town of Augusta, Kentucky. On the afternoon of September 27, 1862, it would become the scene of fighting between 450-500 men of the Second Kentucky Cavalry (C.S.A.) and about 150 men of the local Union Home Guard. The fighting would result in the loss of several Confederate lower grade officers and the destruction of twenty homes and businesses. While this affair is rarely mentioned in descriptions of the Kentucky Campaign, to those who fought there and to those who lived in Augusta, the impact would last generations.

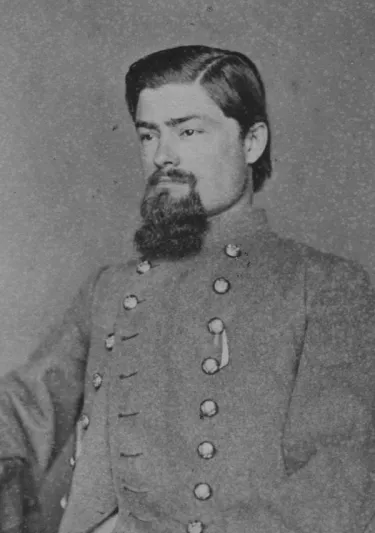

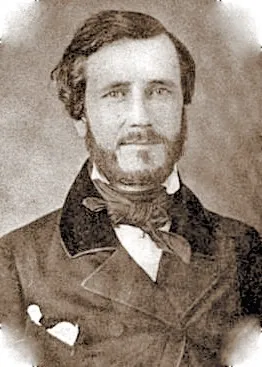

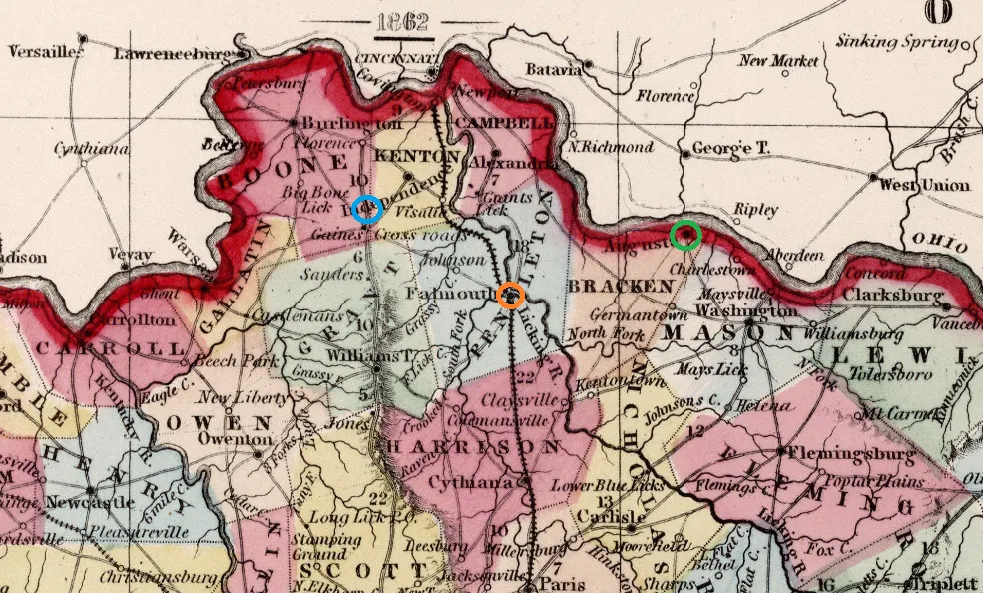

Basil W. Duke commanded seven companies of John H. Morgan’s famed Second Kentucky Cavalry in northern Kentucky while Morgan, with the rest of the Second and the remainder of his command, was trying to hinder the retreat of George W. Morgan’s Federals from Cumberland Gap to Greenupsburg along the Ohio River. Duke was hanging about northern Kentucky to recruit troops to the Confederate cause while also keeping the Federal forces in Cincinnati from moving southward and operating against the Confederate armies occupying the Kentucky bluegrass. Duke used Falmouth, Kentucky as his base of operations, and on September 25, 1862, fought a small engagement at Snow’s Pond, which was situated north of Walton along the main turnpike from Cincinnati to Lexington. Duke was able to capture several Federal troops, and his forces returned thirty miles to Falmouth. By the next day, he was planning to move against Augusta, which was thirty miles to the northeast of Falmouth.

Why Augusta? First, there was a Home Guard unit in Augusta that was transitioning to become part of a newly raised Federal Kentucky regiment. Duke could move against Augusta and break up this organization before it fully formed. Additionally, there was a sandbar on the Ohio River one mile below Augusta that could be easily forded and allow Duke to move towards Cincinnati, possibly pulling Federal forces completely out of northern Kentucky to defend the Queen City of the West. Duke believed he could accomplish this within one full day of departing Falmouth. The Home Guard would cause a revision to Duke’s plans.

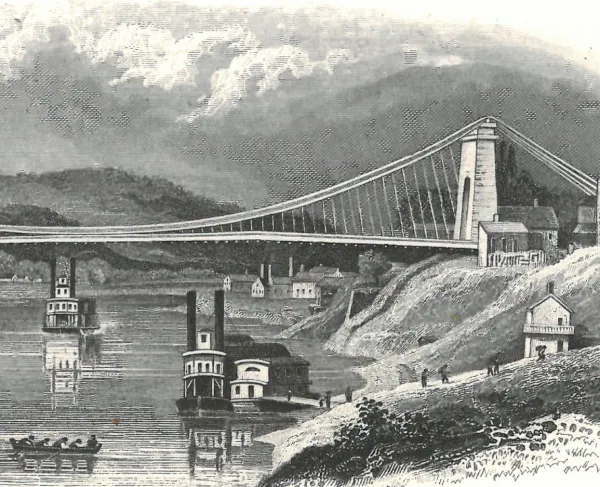

After leaving Falmouth and passing through Brooksville, the Confederates arrived on the hills above Augusta about 1:00 P. M. on September 27th. Duke could see two Federal gunboats on the Ohio River, a third boat having moved downriver in response to a report that Confederates were crossing the river. The remaining gunboats (the Belfast and the Florence Miller) were captained and crewed by civilians, each having a single twelve-pounder howitzer for armament, and a single layer of hay for defense. The guns were to be served by men detached from the 106th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, a mostly German unit raised in greater Cincinnati who were still in the process of mustering into Federal service. In truth, the detached men rarely trained on the guns, and on the Belfast five of the men had deserted prior to the 27th. The Belfast’s gun would be served by just two men, not a crew sufficiently large to ensure efficiency.

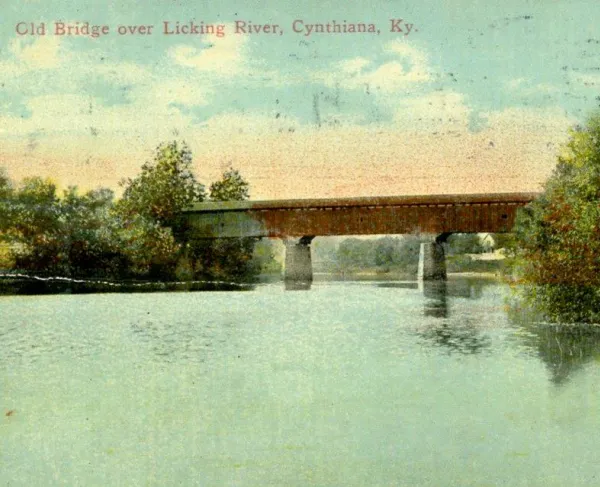

The Federal commander in Augusta was Dr. Joshua Taylor Bradford, who had served as a surgeon on Gen. William “Bull” Nelson’s staff in eastern Kentucky in late 1861 as well as at Shiloh. Dr. Bradford was an expert in ovariotomy and Augusta resident. He had taken ill after Shiloh and was back home in Augusta to raise a new Union Kentucky infantry regiment. Taylor planned to use a “brick and mortar” defense, posting his 125-150 men in various brick homes and businesses in the heart of town, while the women, children, and elderly either fled on the Florence Miller or stayed within the cellars of several buildings. This would allow the gunboats to shell the Confederates until they arrived within town, then Bradford would signal (confusingly with a white flag) the boats to sweep the streets using grape and canister, inflicting damage to the unprotected Confederates while the civilians and men of the Home Guard stayed safe within the brick structures. Some of the Bracken County Home Guard had previously taken part in the fight at Cynthiana in July and had taken shelter in the buildings there while a Federal gun was used in the streets to some success. This information must have been passed along to Bradford who used a similar tactic to defend Augusta.

Unfortunately, this defense, at least the gunboat portion, was not as successful as Bradford had hoped. The Belfast fired two to three shells at the Confederates while they were on the hilltop, even causing some casualties to some of the Confederate artillery crew, but the rebel return fire was too close for comfort for the gunboats. One shell from the Confederate guns (which were a pair of six-pounder mountain howitzers known affectionately as the “bull-pups”) could cause great damage to the poorly “armored” gunboats. Knowing that the boats could not sustain damage the civilian captains of the boats decided to distance themselves from the Confederate artillery and headed upriver. The Florence Miller, filled with some of Augusta’s citizenry, moved away from the Kentucky shore and would become entangled for some time with the Belfast as both boats started to move. Seeing the gunboats leave the town, Duke ordered his advanced guard and Company A of the Second Kentucky to move towards the shore and occupy a sandbar upriver of town. The Confederates charged into the eastern portion of Augusta, dismounted, and moved out on the bar and as the Belfast steamed by filled her with 115 holes from small arms fire. The departing gunboats gave Duke confidence that taking Augusta would now be an easy task and directed Companies B and C to move into the heart of town. However, the Home Guard gave the Confederates a warm reception, being safely ensconced on the second floors of buildings built with two and three layers of brick. The fighting became intense.

Hearing the fighting in the heart of town, the advanced guard and Company A moved from the sandbar and some of the men, having mounted against Duke’s admonishing to avoid being on horseback while moving through town, were in turn shelled by the Confederate artillery on the hilltop. This “friendly fire” caused one Confederate officer to be killed. The Confederates would suffer several losses in their officer ranks before the fighting was over.

The Home Guard, while being armed with “inferior muskets,” was putting up a stout close-range defense. However, some of the Home Guard, seeing the numbers arrayed against them, would raise the white flag and surrender. As the Confederates would attempt to collect these surrendering men, Home Guard positioned in other buildings, or even in other rooms within the same building as the surrendering Home Guard, would continue the fight, angering Duke. He ordered his guns to maneuver into town and while he brought other companies into the fight. The “bull pups” did the trick, firing a point-blank range into the windows and causing more Home Guard to give up the fight. However, this close-range shelling also started a fire, burning some of the trapped Home Guard alive. A total of twenty of Augusta’s buildings would be caught up in this conflagration.

The Home Guard now fully surrendered. The fighting, which lasted sixty to ninety minutes, had been a severe close-range battle. Duke, having broken up the Home Guard, could not proceed with the intended crossing of the Ohio River as he had very little of his artillery ammunition remaining, and without the support of these guns, he did not feel confident in taking his command into the Buckeye State.

Some of the Confederate dead were buried in Augusta, others along the route back to Brooksville, was the retreating Confederates reached the evening of the 27th. Duke would write “That night we reached Brookville after dark, and passed the night there, the gloomiest and saddest that any man among us had ever known.” Ten junior officers had been killed or mortally wounded. Most of the command would head towards Cynthiana, Falmouth no longer being deemed suitable as a base of operations. Duke would spend the night and the next morning paroling some of the more sympathetic Home Guard, and take about eighty prisoners, including Bradford, with him after having a small skirmish the morning of September 28th at Brooksville. These remaining eighty prisoners would later be paroled as well.

The gunboat captains would be lambasted by Bradford in his report of the action for what he thought to be their cowardly retreat. A court-martial was held for both captains. The captain of the Florence Miller, having civilians aboard his craft, was exonerated. Captain David Z. Sedam of the Belfast, despite some compelling testimony about the lack of an experienced gun crew, desertions from those men designated to train on the guns, and damage from small arms fire, was found guilty and sentenced to six months of hard labor. However, this sentence was dismissed as it was pointed out that the captain was a civilian and not subject to the results of the trial.

Augusta is a quiet town with a beautiful riverfront. The town was the setting for some of the mini-series Centennial, and on nice weekends the visitors make their way to the shops and restaurants, bringing tourism dollars to the community. The results of the 1862 “battle” are still evident – many of the town lots do not have a structure built to replace those that were destroyed in the fire. There are a few signs in town for a Civil War walking tour, and within one of the cemeteries there is a monument to eight unknown Confederates killed during the fighting. Additionally, there is a group that has been formed to interpret and educate visitors about Augusta’s Civil War past (civilwaraugusta.org).