In the summer of 1863, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland received orders from Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck in Washington, D.C., instructing them to prepare for a march toward Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Confederate troops. Bragg was busy trying to establish a strong defensive position in Tennessee, but he needed more time. To buy that time, Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan proposed a plan to keep Rosecrans away from Bragg. The plan was similar to one the Union had used in the spring of the same year, when Col. Benjamin H. Greirson led a raid behind Confederate lines for 16 days, covering some 600 miles.

Morgan’s idea was to take more than 2,000 cavalry through Kentucky to threaten Louisville. Next, he would attempt to destroy the Louisville & Nashville Railroad lines that the Union troops depended on for supplies. Morgan proposed to Bragg that his men would then cross the Ohio River into Indiana, turn east for Ohio, re-cross the Ohio River and make their way back to Bragg through Kentucky or possibly West Virginia. Bragg did not approve of Morgan’s plan, but relented that he would allow a raid into Kentucky, under the condition that the raiders would not cross the Ohio River. Ultimately, what was to be a mere distraction became the longest, albeit unauthorized, raid of the Civil War.

Morgan entered Kentucky on July 2, and after five days in the Bluegrass State, the soon-to-be infamous raiders headed north, spending an additional five days in Indiana, before turning east into Ohio. At the time of the Civil War, Ohio was the third-most populous state, behind New York and Pennsylvania. As word of the impending raid reached Ohio, panic ran rampant; nearly all men of fighting age were away, engaged in the many bloody battles that occurred in summer of 1863.

The raiders, happy to be leaving Indiana, gleefully gazed upon the town of Harrison, a small community that straddles the Indiana and Ohio border, around noon on July 13, 1863. Confederate Lt. Col. James McCreary was quite impressed with the setting:

Today we reach Harrison, the most beautiful town I have yet seen in the North. A place, seemingly, where love and beauty, peace and prosperity, sanctified by true religion, might hold high carnival. Here we destroyed a magnificent bridge and saw many beautiful women.

Harrison’s citizens had heard tell of the approaching Confederates. When the Rebels arrived, they were met by locked stores and boarded-up homes, with resident families cowering inside. These minimal defenses didn’t deter the raiders, and in their typical fashion, they started pillaging, helping themselves to anything they wanted, including some unusual items like ladies’ hats and dresses. “They pillaged like boys robbing an orchard,” wrote one Harrison citizen. Morgan’s men managed to leave the town in complete disarray after only a few hours, departing around 3:00 p.m.

Continuing east toward Hamilton, the raiders were ever aware of the threat that Cincinnati, just to the south, held for them. In an attempt to thwart the Yankee soldiers in the Queen City from knowing their exact whereabouts and movements, Morgan discussed false plans within earshot of those he had previously captured, hoping they would report to the next Union force they came across, once they were released.

The fake plan involved an attack on Hamilton, but Morgan’s real plan was to circumvent the Union army and make haste toward the nearest passable ford on the Ohio River. After he released the prisoners, Morgan sent 500 of his men to Miamitown, just east of Cincinnati, and headed northeast with the remaining raiders.

In the meantime, Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside and his thousands of soldiers were hard at work in Cincinnati developing a plan to stop the raiders. Burnside ordered all militia units from 32 southern Ohio counties to report to four specific locations. He told the men nearest the Ohio River to dig in and be prepared to head off Morgan should he try to cross the river.

Halleck, with no idea what General Burnside was facing in Ohio, ordered him to relocate to Knoxville, Tennessee. When Halleck didn’t receive a response, he sent a telegram to Rosencrans in Tennessee on July 13: “General Burnside has been frequently urged to move forward and cover your left, by entering East Tennessee. I do not know what he is doing. He seems tied fast to Cincinnati.” The telegram’s timing coincided with Morgan’s arrival in Ohio and left Burnside with a tough decision: Should he protect Cincinnati or reinforce Rosecrans in Tennessee?

The decision was made for him when he received several reports informing him of the approaching raiders. Ironically, Morgan wasn’t planning to attack Cincinnati. He skirted the city and, on July 14, passed to the north through Loveland, Carthage and Glendale before eventually arriving at Camp Dennison. The Confederates spent the night there and moved on quickly at dawn.

A few days went by without incident, but as the raiders drew nearer to the Ohio River, things took a turn for the worse. The men Burnside had ordered to watch the riverbanks were ready. Those in West Union, Ohio, observed the raiders and watched as Brig. Gen. Edward Hobson and his cavalry followed close behind. This Union force had been secretly following Morgan ever since the Confederates had crossed the Ohio River and entered Indiana earlier in July but, until this point, had failed to catch up. Morgan was also being tracked by a large contingent Burnside had sent out when he saw the Confederates moving past Cincinnati.

Burnside wrote to his fellow general Julius White, on July 14, 1863:

Morgan…is making for the Ohio River, near Ripley. He may be kept from crossing by the gunboats, and he may go above to cross. General Hobson is but 10 miles in his rear with a large cavalry force. They both camped in Clermont County, Ohio, last night. We hope to catch him.

Morgan wished to get out of Ohio and into Kentucky or West Virginia as soon as possible. However, on July 15, 1863, a combination of problems prevented him from crossing, first, near Ripley and, again, at West Union. Morgan was thus convinced that his best opportunity to cross the Ohio River would be at Buffington Island, 120 miles to the east, located on the Ohio–West Virginia border. Morgan had to act quickly; in addition to the two forces on his tail, Union gunboats were patrolling the Ohio River. But reports in a local newspaper on July 17 indicated that the river near Buffington Island was running about two feet deep, far too shallow for any ship.

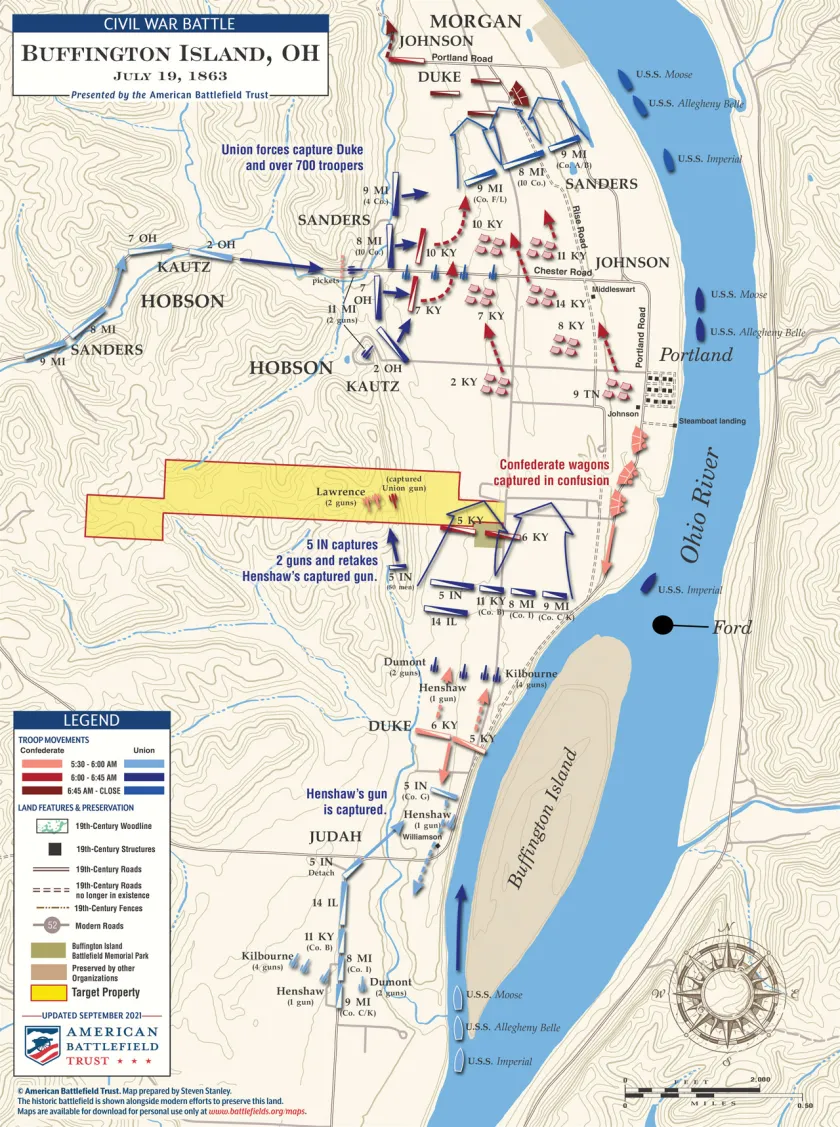

Morgan and his men arrived at Buffington Island on July 18, only to see that the ford was blocked by earthworks put up by hundreds of local militia. The Confederates outnumbered the men hiding behind the entrenchments, but Morgan was unable to launch an attack because dusk was falling fast, and a heavy fog had settled over the area. Not realizing how close behind him Hobson’s cavalry was, Morgan gave his tired men a break and set up camp. He also ordered the hasty construction of flatboats to aid in crossing the river for those who had been wounded in earlier struggles during the raid.

Morgan’s delay proved to be a critical mistake. As morning approached, Union forces hot on the raiders’ trail the past five days converged on Buffington Island.

When the raiders awoke on July 19, they found themselves surrounded by Federals, who had easily slipped into the surrounding hills and roads undetected under the cover of the heavy river fog that had blanketed the area overnight.

Two Federal brigades attacked immediately. More Union troops arrived and nearly cut off all chance of escape. Close to 3,000 Yankees engaged in battle with Morgan’s remaining 1,800 men. To make matters worse, the river actually was deep enough to allow passage for two Union gunboats, the USS Moose and USS Allegheny Belle, which arrived on the scene and opened fire. A third river vessel arrived a few hours later.

While history has named this engagement the Battle of Buffington Island, the vast majority of fighting occurred in the Portland area, not on the island itself.

By 10:00 a.m. July 19, 1863, any remaining Confederate hope of crossing the river at Buffington Island had been lost. Morgan’s best option was to fight his way north and hope to find another ford. But the raiders had been torn apart by Federal forces. In the chaos, Morgan’s second-in-command, Col. Basil Duke, was taken prisoner, along with 750 raiders, while 52 raiders were killed. Morgan made a narrow escape with the remainder of his men and fled upstream. At Belleville, West Virginia, about 300 of them successfully crossed the Ohio River and avoided capture. Morgan was halfway across the river when a gunboat came into view. Knowing the raiders on the Ohio side of the river would be trapped, he turned his horse around and joined them. Morgan and his remaining 400 men spent the next few days hiding from the Yankees and searching for another place to cross.

The longest raid of the Civil War ended on July 26, 1863. While eating breakfast, Morgan received word that another Union force was moving toward him. He quickly rallied his troops and fled in the opposite direction. By this point, every Union soldier in the area was hunting him. The raiders were near Salineville, moving toward Steubenville, when they encountered a group of militia, and Morgan had no choice but to hoist the white flag. Capt. James Burbick discussed the terms of surrender with Morgan: The raiders gave up their horses, arms and equipment in exchange for a safe river crossing. Burbick and his men agreed to join in the crossing.

On the way to the river, Morgan saw two dust clouds approaching. Union forces were heading toward them fast, one from the right and one from the left. Too tired to resist, Morgan halted his men and surrendered again, this time to Maj. George Rue of the 9th Kentucky Cavalry. Morgan recognized Rue, as they had grown up just 30 miles apart and said with a smile, “If I had to be caught, I’m glad it was by another Kentuckian.” Major Rue later noted: “It was a hot July day and they were the tiredest lot of fellows I ever saw in my life.”

The raiders had covered more than 1,000 miles through three states, terrorizing the Midwest for nearly a month. While the raid ended in defeat, many in the Confederacy saw the elusive and quick actions of Morgan as a success by keeping the Midwest in a panic for weeks and restoring some semblance of hope to those in the South. For the Union, the raid inspired a renewed effort in fighting by bringing the war to the Yankees’ front door and making the conflict more personal for those in the North. With the capture of Morgan, along with the recent victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg and Tullahoma, came a new and strengthened hope that complete victory over the rebellious Southern states was at hand.