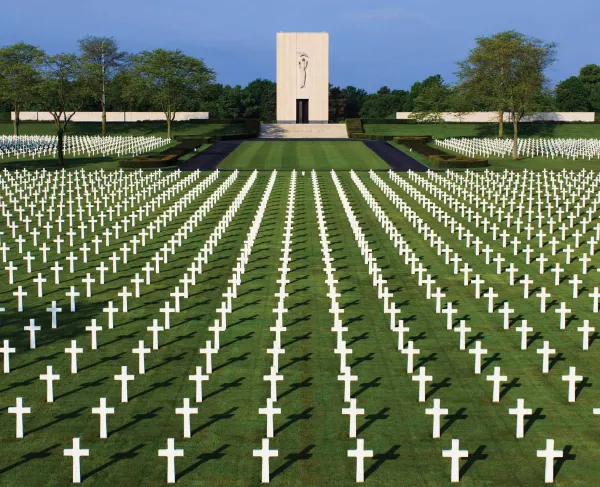

Stones River National Cemetery, Murfreesboro, Tenn.

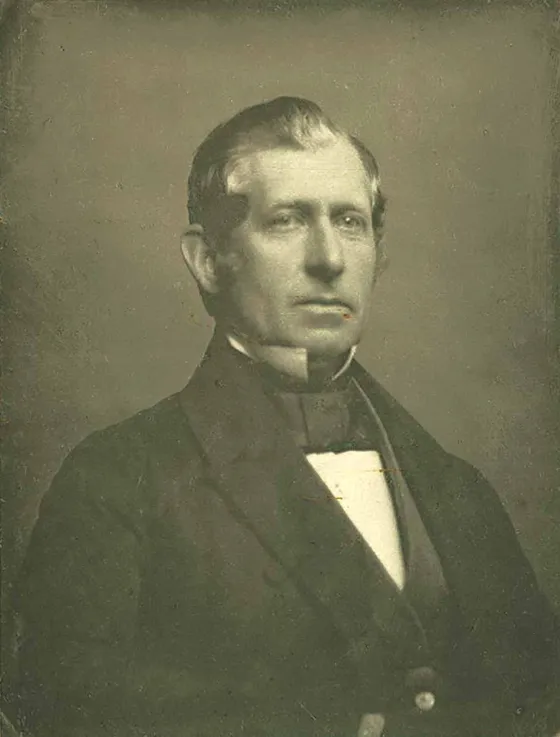

The post–Civil War relocation of Union dead from the battle-ravaged Southern landscape into orderly new national cemeteries by the U.S. Army is partial fulfillment of President Abraham Lincoln’s promise “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.” The lesser-known individual most responsible for this feat is Brevet Lieutenant Colonel and Assistant Quartermaster of Volunteers Edmund Burke Whitman (1812–1883), who was also superintendent of national cemeteries. Based in the Military Division of the Tennessee in the Department of the Cumberland, Whitman led this solemn mission over four years with a deep commitment toward finding thousands of remains, selecting land for new cemeteries and methodically reinterring the dead — all the while creating crucial “mortuary records.” His accountability for the dead across the “interminable grave-yard” left in the wake of fighting led to passage of the National Cemetery Act of 1867, the first substantive legislation to define national cemeteries and provide permanent grave markers for those who served. The United States was the first country to do this.

At the end of Whitman’s tenure in 1869, he submitted to his superiors a remarkable report that spells out the breadth, timeline, methods, ethics and outcome of the reinterment mission. The mortuary statistics on many of the 130 or so pages are valuable, but the report’s unique significance is in its illustrations: sketch views and site plats for about 20 national cemeteries in the report, as well as separate, individual “cemeterial district” maps where the dead were found and their destination national cemetery. Whitman’s remarkably illustrative report is born of some of his pre-war work.

Whitman, 49, enlisted in the Civil War on July 18, 1862. Older than most volunteers but with an eclectic and suitable background, Captain Whitman was assigned duties in Kentucky, Ohio and Tennessee during the war. Whitman was born in Massachusetts, graduated from Harvard College in 1838 and taught in the East until 1855, when he moved to Lawrence in Kansas Territory as a representative of the New England Emigrant Aid Society. He also farmed and oversaw construction, and in the late 1850s, partnered with surveyor Albert D. Searl in real estate investments. Services offered by “Whitman & Searl” included mapping farms, bridges and railroads, and “architectural drawings of every description … town plats, and historical views of scenes.”

Finding the Dead

The U.S. Army had begun to bury its dead at major battle sites in Tennessee before Whitman’s posting there in December 1865 under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, commander of the Department of the Cumberland. Whitman, however, was tasked with the broader scope of “visiting battle-fields, cemeteries, and places where Union dead are interred” throughout the military division, which included Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississsippi and Tennessee.

He oversaw three major expeditions in addition to numerous shorter trips to map the fallen. His findings percolated into “definite cemeterial districts ranged around some central spot, convenient and appropriate,” where a national cemetery was established. The two dozen or so districts were eventually drafted separately by Charles “Chas.” F. Smith, inked on heavy stock in black and filled in with vivid pastel pink, green and blue watercolor washes. The elegant, very small drawings — most scaled at 32½ miles per inch — show geographic features and, in red ink, a flag for the cemetery. Their cheery appearance belies the human mortality they illustrate.

Whitman personally visited “the most interesting places and … most important routes.” He first set out on March 1, 1866, with officers, soldiers and clerks and equipped with “a field note-book and a pocket compass.” That May, some of his findings were used to brief a U.S. congressional committee visiting Memphis about the reinterment effort. Before the group left Tennessee, the essence of the 1867 legislation “with many of its details were … agreed upon,” Whitman later reflected. He was promoted to brevet major the following month and ordered to the “duty of locating, purchasing, and establishing National Cemeteries, and preparing Mortuary Records in the Military Division of the Tennessee.” Disinterment began in October 1866, and in January 1867, Whitman was named superintendent of national cemeteries, though technically it was only for the Department of the Tennessee.

To foster consistency, as early as June 1866, Whitman identified four “principles which should govern in the selection of national cemetery sites.” Major battle sites met the first criteria as “distinguished localities, of great historical interest” to honor the Union’s sacrifice. These included three Tennessee cemeteries Thomas authorized in 1863 — first at Chattanooga (five weeks after Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania), then Stone’s River and Nashville. Army chaplains Thomas B. Van Horne and William Earnshaw were at work in Nashville when Whitman arrived, and he wrote that they were “justly entitled to the credit of being the pioneers in the work of disinterring the dead in the Division.” This trio of sites also reflect two more principles — “points conspicuous … on the great thorough-fares of the nation” and “central points, convenient of access” — considering their proximity to transportation by waterway, railway and roadway. After the war, Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs directed officers in other military divisions to select burial sites for their Union dead, but it was Whitman who established the broad system of reinterments under the quartermaster’s authority before it was codified by law.

National Cemetery Sketches and Plats

Whitman approached his final report as akin to what he probably produced in Kansas, pairing technical plats with charming street-view drawings to create a sense of place. This time his collaborator was Philip M. Radford (1820–1897), a Nashville-based civil engineer with “skill and taste.” Radford made “accurate surveys [and] elaborate sectional plats” of 18 (of 20) national cemeteries, and imaginative views from the perspective of visitors approaching on foot or by carriage. Known photographs of national cemetery landscapes are limited for the late 1860s, so these naïve renderings are among the only and earliest views of impermanent wood buildings, gated entrances and burial sections framed by paths and floral beds.

These plats are also significant because they represent one-quarter of all the national cemeteries as of 1872, when reburials were complete. Collectively, this is the largest number of cemetery plans (as a set) the Army produced until an 1892–1893 atlas. They show clever, thoughtful designs with labeled features: superintendent’s lodges (dwelling and office), a “head board house” to store grave markers, a well (“pump,” covered by an ornamental shelter) and a “substantial and permanent Flag Staff.” About one-third reserve a “monumental site” in keeping with Whitman’s fourth and final principle: that cemeteries should present “favorable conditions for ornamentation, so that surviving comrades, loving friends, and grateful States, might be encouraged to expend liberally of their means, for such purposes.”

Symmetrical or organic, the designs resulted from the topography and the inclination of the officers in charge. The sinuous layouts at Chattanooga and Marietta, Georgia, are atypical for their adaption to low, natural hills where sections are arranged in concentric rows of graves with inward-facing headstone inscriptions. Conversely, on the even grounds of Corinth and Memphis in Mississippi, graves are organized in grids, and at Knoxville, Tennessee, a single circle is formed by concentric rows of graves. In Kentucky, where moving the dead was challenging, smaller numbers of dead were placed in “U.S. Burial Lots” at existing cemeteries, such as the romantic rural-style Cave Hill Cemetery (1846) in Louisville, where the government’s embedded section stands out for its regularity.

The plats also illustrate efforts to organize remains by regiment or state. Typical prioritized tallies in Whitman’s report begin with the U.S. Army and continue through state regiments, Veteran Reserve Corps, “Colored Troops,” employees, miscellaneous and, lastly, the unknowns. Black or white, burial as an unknown was the most distressing outcome for the military and loved ones; These burials are often at the cemetery’s perimeter, even if not labeled on these plats. The plats also show the dead were segregated by race at some cemeteries, where burial sections are labeled “Colored.” These cemeteries include Memphis, Knoxville and Natchez, Mississippi. No federal policy about segregation in death has been found, but Whitman — with a personal history of antislavery activism — was clear. “No distinction is to be made in regard to color so far as the removal to the National Cemeteries is concerned,” he wrote in 1867, “but as the colored troops were a distinct organization, it is considered quite proper and in no way an odious distinction to give them burial either in a separate lot or together in the same part of a lot containing both White and Black. In selecting a separate lot they are in every way, to be treated as if they were white soldiers.”

“Harvest of Death” by the Numbers

Whitman’s report contains daunting numbers. His men visited nearly 2,000 distinct localities, including more than 300 places where fighting occurred and hospitals. They found more than 40,000 scattered graves and documented in excess of 10,000 names. They collected remains from “no less than 6283 distinct spots,” and ultimately, more than 114,500 remains were reinterred into the Military Division of Tennessee national cemeteries. Fortunately for Civil War researchers, these statistics are elevated through the sketches, plats and cemeterial district maps associated with Whitman’s final work.

Whitman mustered out of the U.S. Army on July 15, 1868, but as a civilian he worked another year producing the report that “formed the basis of the elaborate system of National Cemeteries.” He died in 1883, and his eulogy by the Society of the Army of the Cumberland was fitting: “The beautiful cemeteries of the Southern States will remain a perpetual memorial of Colonel Whitman.”

READER NOTE: All quoted material is from Whitman’s final report or correspondence, if not indicated otherwise. The report and individual district maps are part of the U.S. Army Quartermaster’s records (RG 92) at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, and College Park locations, respectively. Another large map of all Whitman’s Civil War cemeterial districts is in the collection of Harvard University Library collection (G3861.G54/1866/C4; 1866?), though it is not currently credited to him.