“Old Simon” watches over Antietam National Cemetery, Sharpsburg, Md.

While the vast majority of cemeteries dedicated to the memory of America’s soldiers, sailors and marines fall under the auspices of either the Department of Veterans Affairs or the American Battle Monuments Commission, a relatively small number of highly significant sites remain under the management of the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service (NPS).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the sites that fall into this category are among the oldest national cemeteries, established during or immediately following the Civil War, excepting Custer National Cemetery in Montana, which relates to the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn. Accordingly, of the 14 national cemeteries overseen by the green and gray, only one remains open to new burials – Andersonville National Cemetery at Andersonville National Historic Site in Georgia. Based on their location, two facilities, Yorktown National Cemetery in Virginia and Chalmette National Cemetery outside Louisiana, might seem likely to hold a large number of burials related to pre-Civil War conflicts. But the former has no Revolutionary War dead, and while the latter has four War of 1812 veterans, only one of them fought in the Battle of New Orleans.

The only true outlier to that pattern of origin is Andrew Johnson National Cemetery at Andrew Johnson National Historic Site in Tennessee, which didn’t see veteran burials until 1909. It had been owned by the Johnson Family until 1906 and used as a family resting place until the will of Martha Johnson Patterson, who had served as her father’s White House hostess, requested that the hill become a burial ground for veterans in a “park-like” setting. New burials took place until 2019, and the more than 2,000 interments represent veterans from the Civil War, Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, Vietnam, the Gulf War and the War on Terror.

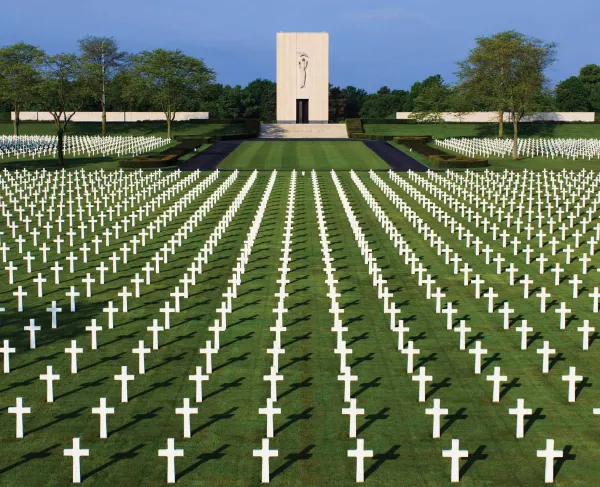

Many of the NPS-led national cemeteries contain spectacular sculptures and statuary. Dominating the layout of Antietam National Cemetery in Maryland, the Private Soldier Monument, affectionately known as Old Simon, towers over about 5,000 burials. At Gettysburg’s Soldiers’ National Cemetery, the central Soldiers’ National Monument is more famous, but an urn standing watch over the dead of the First Minnesota – 52 of the 75 men killed or mortally wounded are buried there – is widely recognized as the first monument placed on the battlefield. During the Victorian era, cemeteries were designed to be beautiful places for surviving families to find solace, and elements of that landscaping philosophy are still readily visible in the undulating curves of Stones River National Cemetery in Tennessee.

The Park Service’s cemeteries vary greatly in size. Battleground National Cemetery in Washington, D.C., is the most petite, covering one acre and containing just 41 burials – 40 soldiers who fell in the Battle of Fort Stevens and one veteran who died in 1936 and requested to be interred there. At the other end of the spectrum, the 40-acre Vicksburg National Cemetery in Mississippi holds the remains of 117,000 Union soldiers, plus about 1,300 veterans of later wars.

Civil War-era national cemeteries were not all neatly collected in centrally located national cemeteries from the outset, and reburial details had to locate, exhume and rebury soldiers who had been buried relatively near where they fell. To populate Poplar Grove National Cemetery in Petersburg National Battlefield, crews relocated 6,718 remains from nearly 100 individual burial sites across nine Virginia counties, stretching as far as Lynchburg.

While fallen warriors being buried as unknowns remains a sad fact of warfare, the scenario was much more common during the Civil War, before soldiers carried government-issued identification. Only about 20 percent of burials at Fredericksburg National Cemetery, which includes some 15,000 individuals from the four major battles around Fredericksburg, as well as the Mine Run and North Anna campaigns, are identified. The ratio is even worse at Shiloh National Cemetery, where 2,359 of the almost 3,600 Civil War burials are unknown. Interestingly, the cemetery includes both a memorial to a soldier killed in the Gulf War and the grave of George Ross, a Continental Army private.

Regulations for these national cemeteries during the 19th century were highly specific and limited to "soldiers who shall die in the service of the country." That provision initially meant only to Union war dead, although the Revolutionary War and War of 1812 burials noted above demonstrate that it was imperfectly applied. But in broad terms, it does mean that no Confederate soldiers are buried in these cemeteries, excepting a handful of known cases of mistaken or overlooked internment and whatever number might be obscured in the vast quantity of wholly unidentified remains. Instead, Confederates who were not returned to their homes might be buried in churchyards near the battlefield, such as the massive Blandford Cemetery, near Petersburg, or left on the battlefield, as was the case at Shiloh.

Both for their incredible symbolism, being hallowed ground in the truest sense, and their intrinsic historical value, upkeep of these cemeteries is a priority for the National Park Service. The 2020 passage of the Great American Outdoors Act, a massive federal investment in conservation and pubic-land stewardship, created an influx of $9.5 billion over five years to address infrastructure and maintenance backlog. And the National Park Service has articulated that upkeep and capital improvements for its national cemeteries is a targeted program through the Legacy Restoration Fund.

Already, masons from the National Park Service Historic Preservation Training Center have descended on Poplar Grove National Cemetery at Petersburg to address failing brick walls enclosing the burial area. They repaired, rehabilitated, and stabilized 30 double wythe masonry recessed panels, used specialized cleaning techniques to remove a century and a half of pollutants, repointed some 1,100 linear feet of deteriorated masonry and replaced unrecoverable bricks. The Park Service is also investigating how these mechanisms can best be used to repair damage caused by flooding at Vicksburg National Cemetery and to systematically address the underlying infrastructure problems that may cause recurrences.