The 5th US Cavalry at Gaines's Mill

By Daniel T. Davis

Lines of infantry in gray and butternut doggedly advanced across the stream. “Our men, full of confidence, rush with irresistible force upon him,” wrote a Confederate brigade commander. “He is driven from his rifle pit pell-mell over his first breastwork of logs…here he vainly attempts to reform and show a bold front, but, closely followed by our men, he yields and, and is driven over and beyond his second parapet.” Victorious Southerners continued to the top of a high ridge. Ahead lay a tantalizing prize, a line of enemy artillery. Suddenly, squadrons of Union cavalry materialized, “bearing down” on the Confederates.

Organized through an act of Congress, the 2nd U.S. Cavalry was formed on March 3, 1855. A number of officers who would gain prominence during the Civil Warꟷincluding Robert E. Lee, John Sedgwick, Wesley Merritt, and John Bell Hoodꟷwere assigned to the unit. Stationed in Texas during the ante-bellum years, the regiment participated in expeditions against the various American Indian tribes.

Following the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the Second was transferred east in preparation for operations against Confederate forces. Two squadrons were present at the Battle of First Manassas on July 21, 1861 where they spent most of the engagement supporting the Union infantry. Less than two weeks later, the Regular mounted units were reorganized by Congress. Part of this effort resulted in the unit’s re-designation as the 5th United States Cavalry. The Fifth spent the fall and winter months in the defenses of Washington, often engaging in reconnaissance missions into Maryland and Virginia. The onset of spring eventually brought an end to the monotony of these duties.

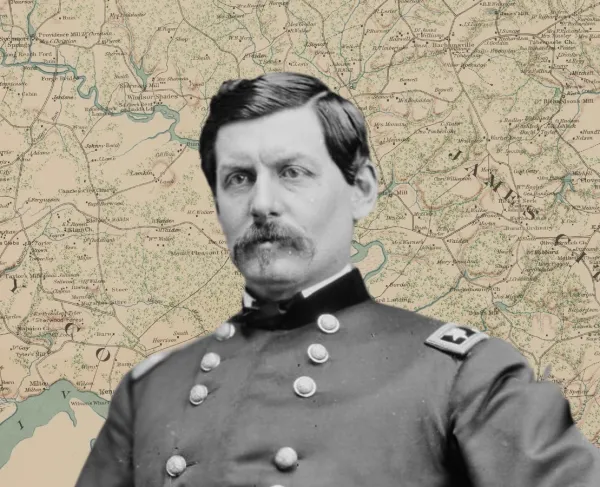

In the middle of March, 1862, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan inaugurated his campaign against Richmond. The first stage of this effort involved the transfer of the Army of the Potomac to the Virginia Peninsula. Part of the Cavalry Reserve, the Fifth was assigned to the brigade of Brig. Gen. William Emory, an officer who had served in the 2nd U.S. The Reserve was commanded by Brig. Gen. Philip St. George Cooke. A Virginian who remained loyal to the Union, Cooke had served in the U.S. Dragoons before the war and authored a manual on mounted tactics. On March 18, the regiment embarked at Alexandria.

After landing at Fort Monroe, McClellan began his movement on the enemy capital. The Federals soon encountered Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Confederate army at Yorktown. During the ensuing siege, the 5th U.S. were engaged in picketing around Lee’s Mill and Warwick Court House. Johnston eventually abandoned Yorktown and withdrew to Williamsburg. Union forces captured the colonial town on May 5 and McClellan’s advance continued.

At the end of the month, the 5th U.S. participated in Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s joint expedition to Hanover Court House. Porter was to secure the Federal right flank and destroy the various bridges over the South Anna and Pamunkey Rivers. Johnston, however, had his eye on McClellan’s left south of the Chickahmony River. On May 31, he struck at Seven Pines. Although the battle was inconclusive, Johnston was wounded. He was replaced by Robert E. Lee, President Jefferson Davis’ military adviser and former Lieutenant Colonel of the old 2nd U.S. Cavalry.

One of Lee’s objectives upon assuming command was the security of Richmond. He hoped that a major offensive might drive McClellan back and induce him to give up the campaign. Before such an undertaking, he required specific information on the disposition of the Union forces. To gather this intelligence, he turned to Brig. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, the commander of the army’s cavalry brigade and Cooke’s son-in-law.

Although the Cooke’s cavalry was unable to check Stuart, patrols from the 5th U.S. engaged him in a brief fight at Linney’s Corner on June 13. This action resulted in the death the only Confederate on the expedition. Stuart successfully returned to Richmond with word that Porter’s 5th Corps was the only enemy force on the north bank of the Chickahominy. Isolated from the rest of the army by the river, Porter presented an opportunity which Lee intended to take full advantage of.

Lee struck the V Corps at Mechanicsville on June 26. Porter’s men held firm throughout the day but after midnight, withdrew to a new position below the New Cold Harbor crossroads near Gaines’ Mill. The V Corps formed on high ground overlooking Boatswain Creek. Cooke arrived on the field with the Reserve that morning and was placed on the Union left. Around the middle of the afternoon, Lee sent his infantry forward against the Union line. Stubbornly, Porter’s men held on. Throughout the fighting, Cooke kept his men in position. Late in the afternoon, a Confederate advance led by Brig. Gen. John B. Hood’s Texas Brigade pierced the Federal line. The blue infantry began to fall back upon several batteries.

Cooke observed the withdrawal and was alarmed by the threat to the artillery. He conducted the 1st U.S. Cavalry and 5th U.S. to a point directly in rear of the artillery. Turning to Capt. Charles Whiting, the commander of the Fifth, he said “As soon as you see the advancing line of the enemy rising the crest of the hill, charge at once, without any further orders to enable the artillery to bring off their guns.” Cooke then directed the 1st U.S. to support their sister regiment and rode off.

Whiting immediately turned to his men and yelled, “Attention! Draw saber!” It was not long before the 5th U.S. prepared to advance. “Almost immediately, the bayonets of the advancing foe were seen, just beyond our cannon, probably not fifty rods from us,” wrote W.H. Hitchcock, a member of the regiment. Whiting advanced at a trot and as he drew closer screamed “Charge!” “We dashed forward with a wild cheer, in solid column of squadrons” Hitchcock remembered. “Our formation was almost instantly broken by the necessity of opening to right and left to pass our guns”. Watching from the rear Lt. Col. William Grier of the 1st U.S. recalled that as Whiting’s men went forward, they were “enveloped in a cloud of dust.”

Confederates under William Whiting and James Longstreet poured a “galling fire” into the ranks of the regiment. Despite this resistance, the troopers continued on through the first line of infantry until they encountered a thick wood. “The audacity of the charge, together with the rapid firing of canister at short range, impressed the enemy with the belief that fresh reserves had arrived on the field” wrote an officer of the 5th U.S. This confusion allowed the troopers to wheel to the right and make their escape. The charge could not, however, stem the Confederate tide. That night, Porter abandoned the field and marched to the southeast.

The 5th U.S. paid dearly for their assault. Of the 237 men who made the charge, 55 were either killed, wounded or listed as missing. Captain Whiting was captured and every officer except for Capt. Joseph MacArthur was a casualty. MacArthur led the men in battle a few days later at Savage Station and remained in the rear for the final battle of the campaign at Malvern Hill.

Following the battle, Fitz John Porter criticized Cooke’s actions and the regiment’s subsequent attack. He blamed them for the overall collapse of his position. “All appeared to be doing well, our troops withdrawing in order…when to my great surprise, the artillery on the left was thrown into confusion by a charge of cavalry,” he wrote in his official report. “The explanation of this is that although the cavalry had been directed…to keep below the hill and under no circumstance to appear upon the crest, but to operate, if a favorable opportunity offered, against the flank of the enemy in the bottom-land. Brig. Gen. P. St. George Cooke, doubtless misinformed, ordered it…this charge…resulted, of course in their being thrown into confusion, and the bewildered horses, regardless of the efforts of the riders, wheeled about, and dashing through the batteries, convinced the gunners were charged by the enemy. To this alone is to be attributed our failure to hold the battle-field.”

Porter’s statement engendered bitterness on the part of Cooke and his cavalryman. While Cooke conceded that he moved the 1st U.S. and 5th U.S. at his discretion, he did not mention that he received a directive from Porter to do so otherwise. Wesley Merritt, an officer serving on Cooke’s staff later wrote “The cavalry did much on that field to restore the fortunes of the day in charging and supporting under the most merciless fire batteries…on account of having no supports, would have been obliged to retire much earlier than they did.” Other officers shared Merritt’s opinion. “But for the charge of the 5th Cavalry on that day, the loss in the command of General Fitz John Porter would have been immensely greater than it was” remembered Lt. Col. J. P. Martin.

Enlisted men, such as Hitchcock agreed with their sentiment. He spoke for his comrades when he wrote after the war “so far as those of the 5th Regular Cavalry present in this charge were concerned, we certainly did our whole duty, just as we were ordered. We saved some guns, and tried to save all.” Hitchcock also mentioned a simple truth that transcended the arguments. “A large number fell in that terrible charge, and sleep with the many heroes who on that day gave their lives for the Union.”

We have a chance to save these critical pieces of history at Gaines' Mill, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House for just a fraction of their full...