The Loyal League

The true history of this war will show that the loyal army found no friends at the South so faithful, active, and daring in their efforts to sustain the government as the Negroes. Negroes have repeatedly threaded their way through the lines of the rebels exposing themselves to bullets to convey important information to the loyal army of the Potomac.

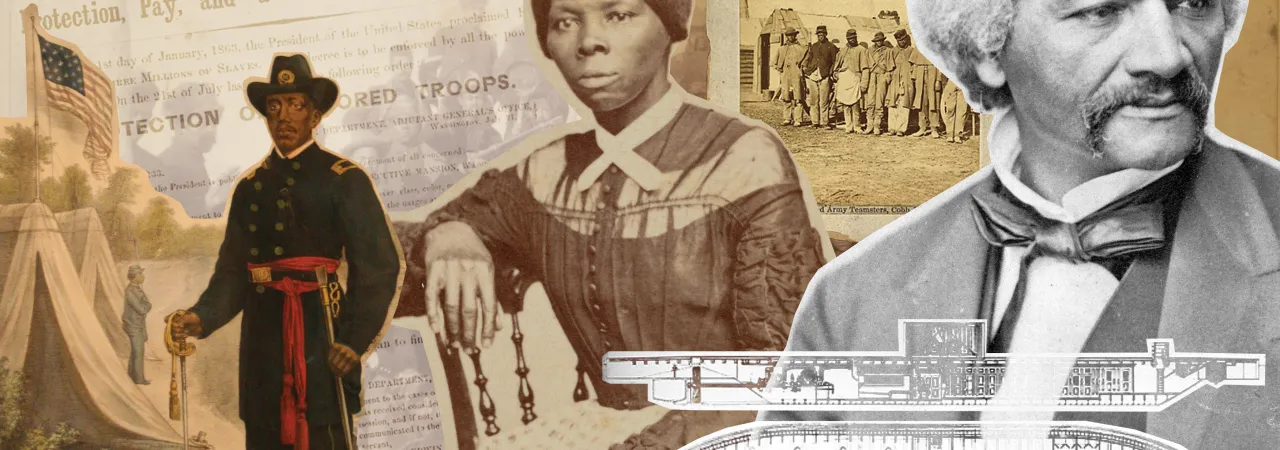

Frederick Douglass, 1862

It may be that the best spies leave no trace. During the American Civil War, African Americans utilized secretive networks for political organizing and gathering military intelligence.

The details are often woefully incomplete in the historical record. Much of the information was destroyed after the war to protect those who provided it, underplayed in deference to the contributions of European Americans or simply lost in the sands of time. Yet we know enough today to appreciate the critical role these African American spies and informants played in shaping their own fate and the fate of our nation. Here are a few things everyone should know about the intelligence contributions of African Americans in the Civil War.

The Loyal League

More than a decade before the war began, African American abolitionists had a choice to make: to work in opposition to, or in league with, the United States Constitution. According to historian Hari Jones, “In the State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio held in Columbus in January 1851, African Americans debated and voted on a resolution concerning this subject. .... At a vote of 28 to 2, the Convention resolved to work in league with the Constitution to gain equal rights as citizens and to abolish slavery.” This convention built on precedents from the 1830’s when free African Americans in Baltimore established the Legal Rights Association to protect and expand civil rights allowed by law at that time. From these ideological foundations like these, both public and secret networks grew in the Black communities, dedicated to securing freedom in league with the Constitution. The Civil War brought new challenges and opportunities for these groups to build political influence and work secretly to support the Union war effort. The groups had various names in the 1860s and in the record of history, like the Loyal League, the Legal League, or the 4Ls: Lincoln’s Legal Loyal League.

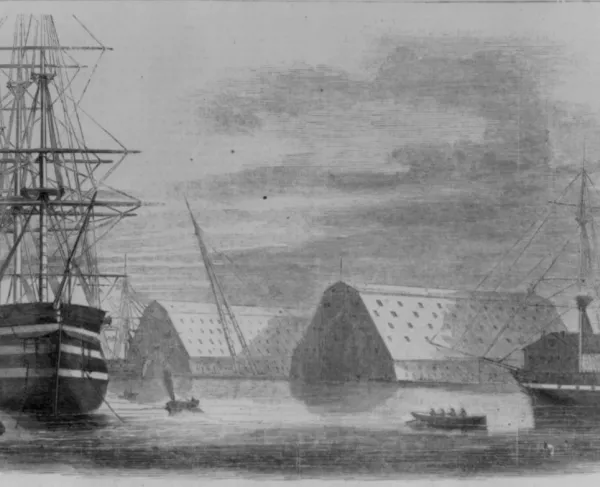

Dueling Ironclads at Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads might never have happened if not for the initiative of a free mulatto woman named Mary Louveste (sometimes called Touvestre). According to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells’s correspondence, she “communicated important and truthful information to me in regard to the Merrimac, during the time that vessel was being iron-clad...and is deserved of consideration for the service she rendered at some risk and expense.” Louveste, who was about 40 years old in 1862, operated a boarding house in Norfolk, Virginia. Her husband worked at the Gosport Shipyard and may have known William H. Lyons, a Union spy. In a likely collaboration with Lyons, Mary Louveste crossed into Union lines in February 1862 to deliver plans of the Confederate ironclad to Secretary Wells. The military intelligence she provided spurred the Union to work urgently on their own ironclad, the USS Monitor, which was ready to confront the CSS Virginia by March 9, 1862.

The Peninsula Campaign

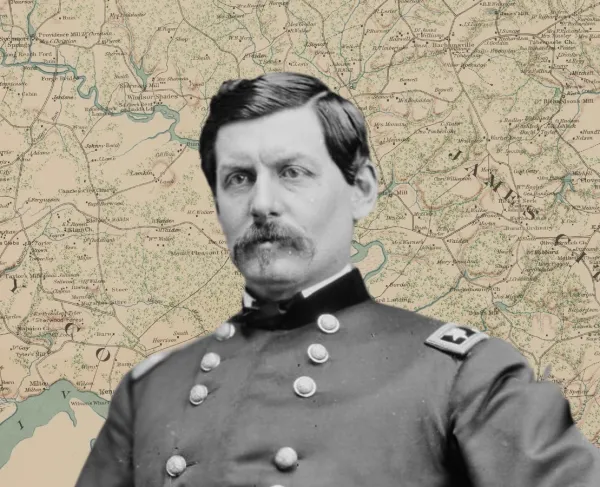

Did members of the Loyal Leagues delay a campaign in hopes that a longer war would lead to emancipation and a clear road to ending slavery in America? In spring 1862, there might have been a misinformation attempt during the Peninsula Campaign as African descent spies from the north infiltrated Confederate lines, working with Allan Pinkerton and collecting information about “the movements of the rebels.” Historian Hari Jones presented a theory: 1) Union General George B. McClellan relied on his head of intelligence, Allan Pinkerton, for estimates regarding enemy numbers and weapons. 2) Pinkerton counted on African American informants as a key source of intelligence. 3) Abolitionists worried that if McClellan captured Richmond in this 1862 campaign, the war would end while the institution of slavery was still basically intact. 4) McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign failed in part because McClellan dramatically overestimated the size of the Confederate force. (Read the details here!) Coincidence, or strategic misinformation campaign?

The Most Famous African American Spy

Harriet Tubman is probably the most famous African American spy of the Civil War. She helped orchestrate the Combahee River Raid, in South Carolina. As a spy in the region, Tubman developed intimate familiarity with the area and its inhabitants. She guided Union Colonel James Montgomery and his men on a successful mission to destroy millions of dollars' worth of Confederate supplies and rescue more than 800 slaves.

These examples just scratch the surface of this intriguing area of inquiry. To learn more about the military contributions of African Americans to the Civil War, explore our collections on the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and African Americans in America’s Wars. To learn more about the contributions of African American spies, watch Hari Jones’ lectures on African American Civil War Espionage.

Related Battles

369

24