Hampton: Ironworks, Plantation and Summer Home

Hampton National Historic Site.

Located twelve miles North of Baltimore, Hampton Hall was once a grand mansion and plantation. Built in the classical Georgian style with Greek and Roman influences, it was larger than George Washington’s Mount Vernon and more lavish.

The land was initially granted to the Darnall family in the late 1600s. It was then bought by Colonel Charles Ridgely in 1745, beginning the family’s seven generations of ownership. The 1,500 acres were originally used for growing tobacco. However, Ridgely and his two sons, Charles and John, saw other uses for it. Because the land was heavily wooded, near a tributary of the Gunpowder River and rich in iron ore and limestone, they established Northampton Ironworks in 1761 or 1762. The furnace produced a wide array of items such as pans, flat-irons, pots, stoves and pig iron. Prior to the Revolutionary War, the Ridgelys, who also owned a fleet of merchant ships, exported their iron (and some crops) to Britain, bringing back finished goods.

Colonel Ridgely and John Ridgely both died in the early 1770s, leaving the business and land to Captain Charles Ridgely. Captain Ridgely, a patriot, used the furnace to support the revolutionary cause. The business produced kettles, cannons and (2-18 pound) cannon balls. The demand for iron products during the war significantly increased Ridgely’s wealth. Ridgely capitalized on his riches and the British loss by purchasing property confiscated from loyalists. This increased his landownership to nearly 25,000 acres.

Captain Ridgely began construction on Hampton Hall in 1783 with the intention of summering there. It is thought that the home’s architecture came from the grand country houses in England. He employed Jehu Howell, master carpenter, to construct the 24,000 square feet mansion. The manual labor was carried out by craftsmen, artisans, indentured servants and enslaved people. While Captain Ridgely became known as “the builder” of Hampton Hall, he died the same year it was completed, 1790. His nephew, Charles Carnan Ridgely, inherited the estate and business. In addition to the ironworks, Carnan Ridgely expanded Hampton’s output to include a variety of crops, livestock and horse breeding and racing.

Outside of the plantation, Carnan Ridgely held political offices. He represented Baltimore County in the Maryland State House of Delegates from 1790 to 1795. He then held a Maryland State Senate seat from 1796 to 1800. The highest position he occupied was Governor of Maryland from 1816 to January 1819. In his role, he sought to make improvements to Maryland’s infrastructure, such as roads, and increase access to education by funding free schools. At the conclusion of his governorship, Carnan Ridgely retired to Hampton. Sometime in the 1820s, he closed the ironworks in favor of focusing solely on crop production.

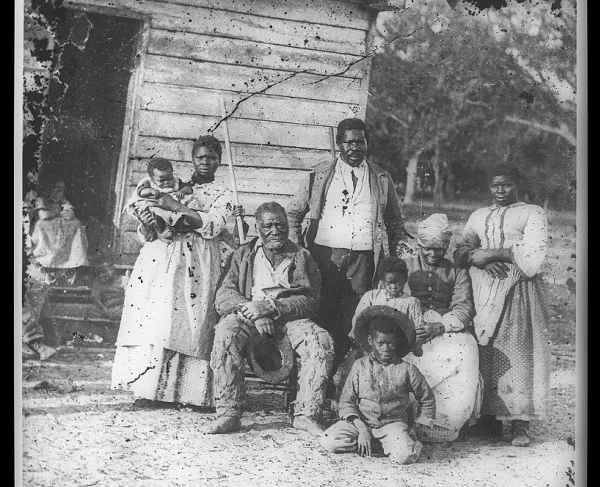

The Ridgelys depended on a wide range of labor to run the ironworks, plantation, and household. In the early days, Colonel Ridgely employed indentured servants, convicts, and British prisoners of war. Furnace work included chopping wood, digging out and moving the iron and casting it. This labor was dangerous and exhausting; between 1775 and 1777, five laborers died. Following the Revolutionary War, the ironworks operations depended on enslaved labor as well. Hampton’s dependence on slave labor increased over time. When Captain Ridgely began building the house, 130 enslaved people worked at the furnace or plantation. By the time Carnan Ridgely died, that number was around 350; its peak was near 500 enslaved people. Slaves at the plantation were gardeners, field hands, jockeys and dairymaids. For the family, they drove carriages, cooked, cared for the children, cleaned, and made and mended clothing. By the time slavery ended at Hampton, in 1864, over 80 laborers (enslaved, indentured, or convict) had attempted to escape; countless advertisements for their capture appeared in local newspapers.

Following the death of his beloved daughter, Sophia Howard, Carnan Ridgely made a codicil (addition) to his will. He ordered delayed emancipation for his slaves, likely influenced by Sophia’s abolitionist views. Enslaved women between age 25 and 45 and men between 28 and 45 were immediately freed along with children under two; of the 350 slaves, 100 were free immediately. Those that did not yet fall within that age range would eventually get their freedom. Those who were older than 45 continued to be enslaved until emancipation in 1864. This act left Carnan Ridgely’s son, John, with a large plantation and few laborers to maintain it. He ultimately purchased over sixty more slaves and employed free laborers, including his father’s former slaves.

Hampton and the Ridgelys hardship began following the Civil War. With slave labor no longer legal, the Ridgelys turned to tenant farming, which generated minimal revenue. The property also continued to be divided amongst heirs, making it smaller and smaller. By 1872, the acreage of Hampton Hall had dwindled to 1,000. The Hall stayed in the Ridgely family until 1947 when it was sold to the National Park Service (NPS). It was the first site to be purchased by the NPS because of its “architectural merit.” Sometimes called “The House in the Forest” and “The Palace in the Wilderness,” it became an established historic site in June 1948. Today, the home and site educates visitors about the Ridgelys, ironworks, plantation life and enslaved people.