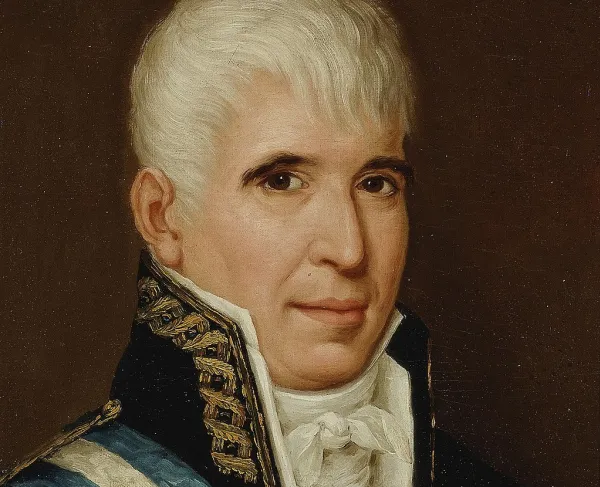

James McHenry

James McHenry was born on November 16, 1753, in Ballymena, Antrim Co., Ireland (now Northern Ireland). His parents, Daniel and Agnes McHenry, raised James and his two siblings in the Presbyterian faith. At the time, the Church of Ireland’s disagreement with Presbyterian beliefs led the Irish Parliament to pass the Penal Laws creating religious discrimination. With his Presbyterian faith, McHenry faced limited educational opportunities and could not hold political office. Following a brief stint at the University of Dublin and the death of his sister, McHenry left Ireland and its restrictions for the colonies and their possibilities.

McHenry arrived in the colonies around 1771, aged 18. He attended Newark Academy where he learned liberal arts and sciences. McHenry encouraged his family to follow him to America. They joined him in 1772, settling in Baltimore, Maryland, where his father and brother set up an import business, Daniel McHenry and Son, which sold a variety of items. McHenry, however, began an apprenticeship with Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia where he oversaw Rush’s pharmacy and managed the finances. Rush was an active member in the Sons of Liberty and connected with many key players in the American Revolution; it is likely that McHenry met some of them while in Rush’s employment.

When the fighting broke out in Boston, McHenry went north and aided the colonists. There, he acted as a volunteer assistant surgeon in a military hospital. McHenry received his commission as a surgeon for the Fifth Pennsylvania Battalion on August 10, 1776 serving under Colonel Magaw. Nearly three months later, Magaw surrendered at Fort Washington, making McHenry and the 2000 other troops prisoners of war. While prisoner, McHenry corresponded with George Washington about prisoner treatment and care. After one year, he was paroled to his home and finally freed through a prisoner exchange in March 1778.

McHenry briefly rejoined the Continental Army as senior surgeon before accepting the position of assistant secretary to Washington. This career change marked the end of McHenry’s medical practice and came with no military rank. For over two years McHenry managed and drafted Washington’s correspondence; many of Washington’s letters preserved today are in his handwriting. Following the Battle of Monmouth, John Laurens noted that McHenry was “worthy to wield the sword as the pen.” McHenry joined the Marquis de Lafayette’s staff in 1780 as an aide-de-camp and shortly thereafter was made a Major in the Continental Army. McHenry witnessed the fighting at Yorktown and Lord Cornwallis’ surrender.

McHenry left the Continental Army in 1781 when he was elected a Maryland state senator. He held a legislative seat for a total of ten years, while also acting as a Maryland representative to the Continental Congress (1783-1786). McHenry attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787, though he missed much of it due to his brother’s illness. Nevertheless, McHenry was a signer of the constitution, one of four Irishmen.

In 1796, President Washington chose McHenry to replace Timothy Pickering as the Secretary of War. In this position, McHenry oversaw all military and naval decisions, trying to streamline military processes and procedures. He convinced Congress to approve the establishment of a 20,000-man professional standing army. While working with Native Americans to build relationships, he also had fortifications built in Western territories. In 1798, McHenry started preparing the country for war against France, though the United States ultimately remained neutral.

One of McHenry’s greatest challenges as Secretary of War was his relationship with the new president, John Adams. Though both were Federalists and supported a strong national government, they disagreed on the direction of the party’s platform. Like other Federalists influenced by Alexander Hamilton, McHenry resigned from his cabinet position in 1800.

McHenry retired to his estate “Fayetteville,” named for the Marquis de Lafayette, just outside of Baltimore. He lived there with some indentured servants, enslaved people and his immediate family. He and his wife, Peggy, whom he married in 1784, had only one daughter and two sons who lived to maturity. McHenry dabbled in local real estate, other investments and worked with his brother in the family import business. Politically, he supported Jefferson during the election of 1800, and when Democratic-Republicans accused him of misusing funds as Secretary of War, he wrote a lengthy letter in his defense.

McHenry opposed the War of 1812. However, his name gained recognition when Fort McHenry, named for him, became the British Navy’s target during a 25-hour bombardment. When the Baltimore fortification withstood the attack and raised its large flag, the scene inspired Francis Scott Key’s poem The Star-Spangled Banner. During the bombardment, McHenry himself sheltered at home with his wife and daughter.

McHenry died, likely from a fever, on May 3, 1816, at age 62. He was buried in Westminster (Presbyterian) Churchyard in Baltimore, Maryland. In a notice of death, The Charleston Daily Courier shared that McHenry was “a man loved, respected and esteemed by all good men.” Historian Bernard Christian Steiner wrote that McHenry “was not a great man, but he participated in great events and great men loved him, while all men appreciated his goodness and the purity of his soul.”

Further Reading: