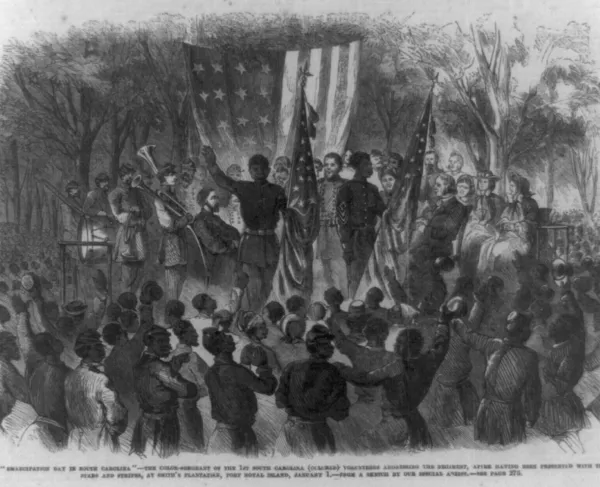

As Prince Rivers stood on a freshly constructed platform in the shade of moss-covered live oak trees at Camp Saxton, he looked down upon the faces of nearly 5,000 newly emancipated people. On this day, January 1, 1863 - also known as Emancipation Day - President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was to be read aloud to those eagerly waiting in the crowd, which included the men of the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. The soldiers of this regiment, including Rivers, were formerly enslaved African Americans from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, as well as the Georgia and Florida coasts, and even as far away as southern Virginia. With the reading of this presidential proclamation came the recognition of their official freedom, as they lived in Federal-occupied territory, although this was just the beginning of what was to be a long journey toward equality and citizenship in the United States. They had already taken the first steps toward emancipation more than a year earlier.

By the Spring of 1862, US Army and Navy forces had a well-founded foothold in Beaufort County, South Carolina. During the previous fall, their arrival had driven white landowners, enslavers, and Confederate troops from Port Royal Sound, and likewise threw open the door for self-emancipated African Americans to seek refuge behind US lines. The opening act of emancipation that began here allowed for approximately 10,000 Black residents to start new lives outside the bonds of slavery. The door was opened for them to receive an education, own land, worship freely, and, for many men of the region, to bear arms in the name of freedom - a period of time between 1861 and 1865 often referred to as the “Port Royal Experiment.”

With a heavy US presence in the Sea Islands came the establishment of the army’s Department of the South in March 1862, which was headquartered on Hilton Head Island and encompassed federally controlled territory from the South Carolina Lowcountry to the coast of northeastern Florida. While in command of this department, General David Hunter, a staunch New York abolitionist, proposed the recruitment of African American men from within the department’s reach. By May 9, 1862, Hunter declared martial law within his department and likewise issued General Order No. 11, which announced that “The persons in…Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida, heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.” Hunter’s proclamation, although not federally sanctioned, allowed for the recruitment of Black soldiers for the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, which began that same month.

Among the first to enlist in the regiment was Prince Rivers, who had been enslaved and worked as a coachman in Beaufort County, but self-emancipated with the arrival of US troops in the region. Rivers was later described by the regiment’s commanding officer, Colonel Thomas W. Higginson, as a man of “distinguished appearance…being six feet high, perfectly proportioned, and of apparently inexhaustible strength and activity.” Higginson added, “No antislavery novel has described a man of such marked ability…if there should ever be a Black monarchy in South Carolina, he will be its king.” As a highly respected member of Company A, Rivers quickly rose to the capacity of Provost Sergeant and even became somewhat of a spokesperson for the men in the ranks. When he later addressed a crowded church in Beaufort and reflected on the regiment’s newfound freedom, Rivers noted, “Now we soldiers are men - men for the first time in our lives. Now we can look our old masters in the face. They used to sell and whip us, and we did not dare say one word. Now we aren’t afraid, if they meet us, to run the bayonet through them.” Unfortunately for many men of the regiment, their initial excitement was checked by Lincoln’s denial of Hunter’s orders and the subsequent disbandment of the battalion. Those who had been taken to the Department’s headquarters on Hilton Head Island for training were furloughed in early August, although Rivers and the men of Company A remained intact and stationed on St. Simon’s Island in Georgia. Although the First South Carolina, as a whole, had effectively concluded their service for the time being, it didn’t last long.

On August 16, General Rufus R. Saxton, military governor for the Department of the South, addressed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to again propose the idea of recruiting from the formerly enslaved population of the South Carolina Sea Islands. His letter was penned with a sense of urgency, as the department was losing troops who were transferred to the ranks of the Army of the Potomac, and, as Saxton noted, “the people suffer greatly from fear of attack by their rebel masters.” Less than two weeks later, Stanton replied to Saxton’s request, authorizing him to “arm, uniform, equip, and receive into service of the United States such number of volunteers of African descent… not exceeding 5,000…” He added, “…all men and boys received into the service… who may have been the slaves of rebel masters are, with their wives, mothers and children, declared to be forever free.” With this authority, Saxton again began active recruitment for the First South Carolina Infantry not just in the South Carolina Sea Islands, but throughout the Department.

Susie King Taylor, an educated freedwoman from near Savannah, Georgia, encountered the men of Company A, commanded by Captain Charles Trowbridge, in the Summer of 1862, as they were stationed on St. Simon’s Island. At just fourteen years old, she was already teaching a school of formerly enslaved children and adults on the island - a trade which she continued as she joined the ranks of the First South Carolina as an educator, laundress, and nurse. Taylor accompanied the men of the regiment when they left the island in October, at which point she later recalled, “…the order was received to evacuate, and so we boarded… a transport, for Beaufort, S. C. When we arrived in Beaufort, Captain Trowbridge and the men he had enlisted went to camp at Old Fort, which they named Camp Saxton.”

While encamped along the Beaufort River, just four miles south of the waterway’s namesake, the regiment grew with the arrival of more self-emancipated freedom fighters who had arrived within US lines. Their daily routine in the fall of 1862 consisted of drill and the ultimate preparation for war, while eagerly waiting for the chance to strike a blow against the institution of slavery. By January 1863, the ranks of the First South Carolina had swelled to upwards of 900 men. The freshly recruited regiment officially mustered into service that same month, soon after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was read aloud in their camp for an attentive audience. The colors which were presented to the men that day took on a whole new meaning, as Colonel Higginson later noted it was “the first day they had ever had a country, the first flag they had seen which promised anything to their people." Emblazoned upon the folds of the national colors were the words “The Year of Jubilee Has Come!” When Rivers took a hold of the colors, he expressed his excitement as he couldn’t wait to “show it to all the old masters.” Color Corporal Robert Sutton agreed, stating they must “show their flag to Jefferson Davis in Richmond.”

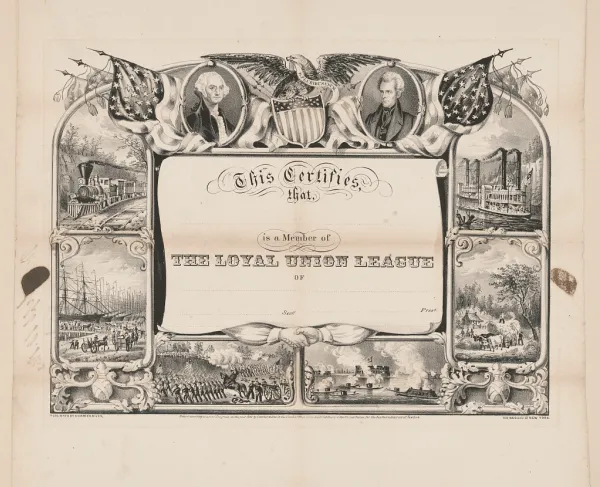

What unfolded at Camp Saxton was only the beginning. The men of the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry helped set into motion what would become a revolution of the Reconstruction Era. Throughout their subsequent three-year enlistment, they witnessed the recruitment of more Black troops in the Lowcountry, and soon after, the mustering in of northern regiments such as the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. In May 1863, the Federal government created the Bureau of United States Colored Troops, which opened the door for approximately 180,000 Black men to enlist in the US Army. The First South Carolina joined the ranks of this organized effort as they were re-designated the 33rd United States Colored Troops in February 1864. Their actions not only helped turn the tide of the war but with each enlistment came a major step taken toward citizenship in a country they could finally call their own.

Further Reading

- Army Life in a Black Regiment, By: Thomas W. Higginson

- Reminiscences of my Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers, By: Susie King Taylor