In the latter half of 1814, British men-of-war had blockaded American ports up and down the Eastern Seaboard, effectively leaving the U.S. Navy bottled up in port. The frigate Congress lay in Portsmouth, N.H.; United States and the new frigate Macedonian were in New London, Conn.; and Constellation was so stymied in Norfolk, Va., that it had seen no action at all during the war.

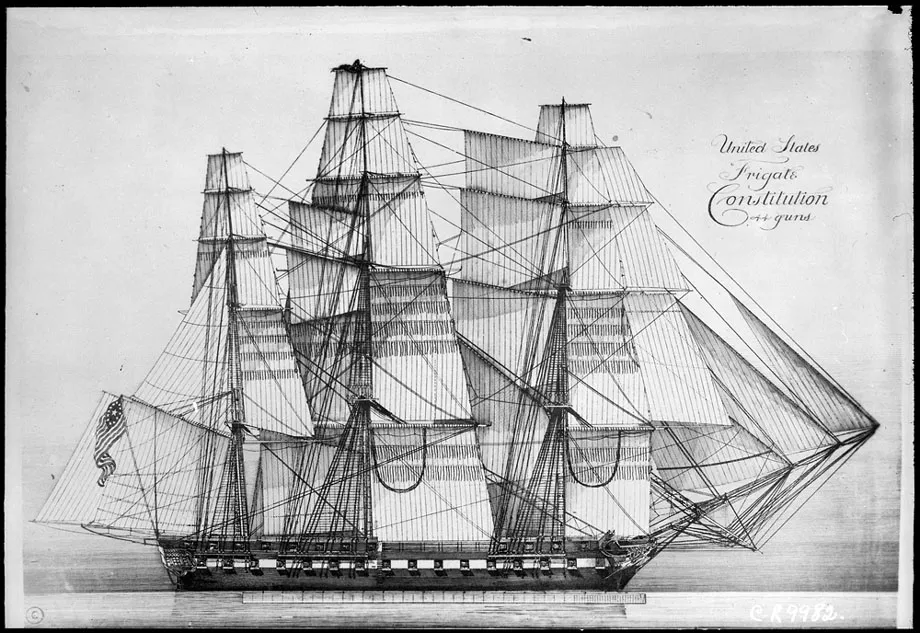

The US Frigate Constitution had been languishing in Boston since April, held there by a squadron of British ships sailing off and on the President Roads. By mid-December, though, the British had reduced their blockade of Boston to only two frigates, HMS Newcastle and Acasta, and an 18-gun brig, HMS Arab. Confident that Constitution was not fit to sail, the Admiralty had reassigned the other vessels or sent them into Halifax for upkeep. Charles Stewart, now in command of Constitution, was chafing to escape to sea. Finally, with clear skies, crisp, sunny weather and the paucity of British blockaders, he determined that the opportunity was at hand and, on Sunday, December 18, he kissed his bride of only one month farewell and ordered his crew to make all sail so they might take advantage of the fine northwest breeze. He was cheered by the populace crowding Long Wharf to see him off, as he sailed swiftly down Boston Harbor, through President Roads, and into the open sea. His was the only American frigate to get to sea, and he planned to take advantage of that!

Stewart and his officers were fully aware of the fact that should they get into any trouble that required port facilities, they were out of luck. With the blockade covering most of the coastline, there was little likelihood that the ship could sail safely into any American harbor. And yet, he knew that Americans expected their ship to prevail in any contest it might find and do everything within the realm of possibility to further the cause of American liberty. So, bolstered by their good fortune in escaping from a nearly eight-month confinement in Boston, Stewart set his course to the south, looking for any British warship that might have strayed too far from the blockade and be ripe for the plucking.

He was unsuccessful in finding any ships, British or otherwise, as far south as the Chesapeake Bay and decided to make for Bermuda, where he was almost certain there would be British shipping, both commercial and navy. The weather was dreadful; head winds and rough seas hampered his progress, his provisions were in short supply due to their hasty departure from Boston, and the ship was wet below decks from leaky gunports and heavy seas. Life was miserable, but morale was still high, the men and officers looking forward to a successful cruise.

Within a few days, Stewart’s lookouts reported a sail. Thinking it might be a straggler from a British convoy, Stewart went to investigate and found a damaged schooner showing the signal for distress. As Constitution approached, Stewart had the British flag hoisted. Now close aboard, he hove to and the unfortunate schooner sent over a boat with the ship’s papers. The Americans discovered that the schooner Lord Nelson had been damaged in the same storm that had made life on Constitution so miserable. Stewart put a prize crew aboard, hoisted the American flag (to the horror of the British captain) and sailed in company with the captured schooner after the rest of the convoy. As it turned out, the capture was most fortuitous for Constitution; her prize was well provisioned with foodstuffs of every imaginable stripe — dried and corned beef, salted and smoked fish, fruits, sugar, spirits, tea and flour. The bonanza of cargo was quickly transferred to the poorly stocked American frigate, and the captured schooner scuttled, as she was of no further use. Constitution continued on, still in search of the rest of the convoy.

They saw several ships, but foul weather precluded bringing them to. January proved an unproductive month, but on February 8, Stewart spoke to a neutral ship, the barque Julia bound to Lisbon, and heard the rumor of a peace treaty between England and the United States. Later that same day, Stewart boarded a Russian ship and corroborated the news. Of course, the treaty had only been agreed to by the negotiators, not approved and signed by the respective governments. Until such time as that occurred, his country and England were still at war.

Constitution continued her patrol, approaching Cape Finisterre in big winds and rough seas. The weather was so cold that staying topside for any length of time became arduous. The lookouts were slacking off, and a near miss with a Portuguese frigate could have proved disastrous.

Fortunately, the ship’s dog, a terrier named Guerriere, saw the ship from his perch atop a carronade and began to point, the mark of a fine hunting dog. The quarterdeck watch saw what had drawn the dog’s notice and sent the ship to quarters (battle stations). They could not identify the warship bearing down under full sail from the windward side; she offered no flag and no recognition signal. It took several shots from the weather deck carronades to elicit a response from the stranger, which turned out to be Portuguese. Fortunately, no damage was done to either ship, and after a brief shouted conversation (the sea was too rough for either to board), the two went on their respective ways.

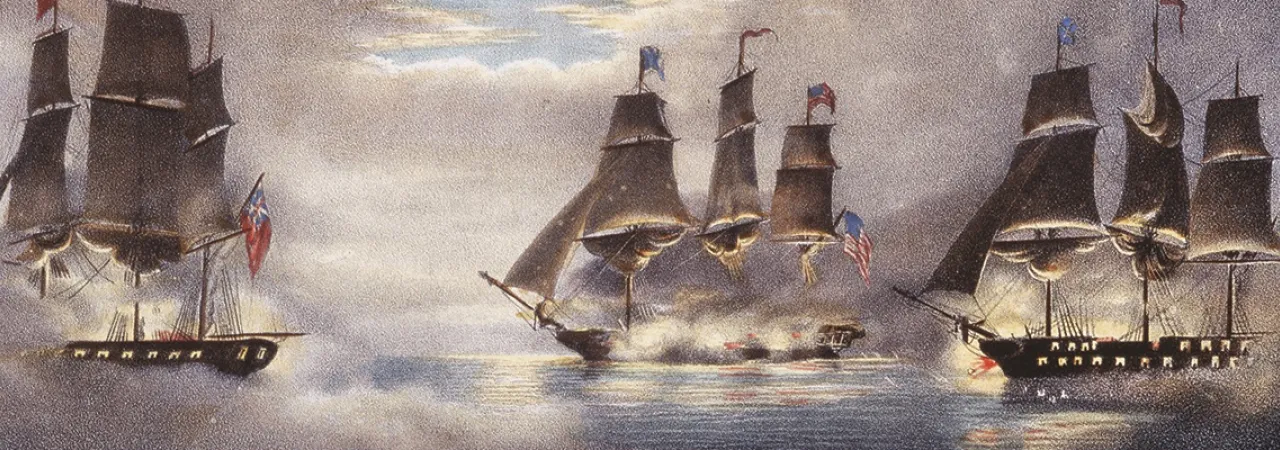

Constitution’s presence off Gibraltar, a major British base, along with her capture of several merchant vessels, had not gone unnoticed; Stewart’s lookouts had seen no enemy ships, but he knew it would be only a matter of time before they came out to investigate. Early in the afternoon of February 20, a full-rigged ship was espied heading toward Constitution from the larboard (port, or left) bow. Shortly after that, another ship became visible beyond the first one. They all closed for some two hours and, clearly visible to Stewart’s lookouts, the two unknowns began signaling one another before turning to the south, apparently to join forces. Stewart was almost positive the ships were British and crowded on sail in chase.

He assumed, he wrote later, that they signaled each other to remain together so as to combine forces; while neither ship alone had a chance of taking an American heavy frigate, together they might prevail.

During the chase, Constitution, with every stitch of canvas set, suffered a small setback; her main royal mast cracked and then fell. Quickly, Stewart sent men aloft to cut away the damaged spar and send up a new one. His skilled crew had the repair effected and the ship back under full sail in only an hour. And they were closing on the two British ships.

The two had indeed joined forces and, preparing for battle, sailed in a line astern, separated by some one hundred yards. Their formation became their undoing.

Constitution held the favored weather position and ranged alongside the aftermost of the two enemy ships. She turned out to be the larger of them, HMS Cyane, a frigate of 24 guns. The American’s momentum carried her slightly ahead, so she lay between the two British ships. Stewart sent a ball between them, beginning the engagement. An exchange of broadsides followed, killing two Americans early in the fight. Darkness was fast approaching, and smoke wreathed the ships and the seas between them. Taking advantage of the poor visibility, Cyane altered course to try and pass under Stewart’s stern for a raking shot. The American captain glimpsed their intentions and essentially stopped his ship, blocking the move, and simultaneously, commenced a heavy cannonade into the enemy. Marines, stationed aloft, added musket fire to the fusillade, forcing the British sailors and officers to “keep their heads down.” As Cyane staggered under the weight of American metal, the other British ship, the 18-gun Levant, wore around to attempt to cross Constitution’s bow and rake her. Stewart responded quickly, filling his sails and again preventing his enemy from gaining any advantage. He offered Levant a couple of raking broadsides from astern at almost point-blank range. The British ship sailed off to leeward in an attempt to escape the galling fire.

The lookouts in Constitution hailed the deck that Cyane was showing signs of life, trying to get moving and rejoin the battle. Stewart jibed around and offered his starboard battery to the enemy. Only 50 yards separated the two ships. Seeing the position he was in, the captain of Cyane struck his colors. Stewart sent a contingent of Marines aboard to take possession of the ship and set off after the escaping Levant.

The superior sailing abilities of Constitution, along with a significantly heavier weight of metal, convinced the British captain that he too should surrender. Constitution¸ the premier American frigate, had taken two enemy ships simultaneously, and fought most of the engagement in the dark!

The three ships—two prizes and the American frigate—sailed in company for the American coast, but they ran afoul of another British fleet, which re-captured Levant. Constitution returned to the United States with Cyane still her prize, to discover the war was already over. Cyane was absorbed into the American Navy as US Frigate Cyane.