Two Wars for Independence

If the American Revolution was the birth of the United States, the War of 1812 was its coming of age. Despite winning the Revolutionary War, the United States was still unstable, and the ultimate success of the “American Experiment” was still far from certain.

From 1783-1812, the newly minted United States faced many growing pains. The legislative power of the central government was hotly disputed. Promises made by the Continental Congress remained unfulfilled. Native Americans contested the growing frontier. Aftershock rebellions wracked the northwest. The military was too small, too weak, to contend with enemies foreign and domestic. The situation was precarious, with the United States needing stability at home and legitimacy abroad.

American westward expansion, and its collision with the Native Americans, was a source of constant friction to the new nation. The British, eager to slow the United States’ rise, supported an “Indian State” around the Great Lakes to check American expansion and create a buffer for British Canada. Fur trade in the region was booming, giving the British added incentive to cooperate with the Native Americans. To facilitate this, the British occasionally provided the Native tribes with arms and supplies. These small provisions were exaggerated, in turn, by indignant and worried Americans. Continued British involvement was seen as an affront to American sovereignty.

The growing commercial and naval strength of the United States also contributed to the outbreak of war. American neutrality during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars allowed for a lucrative trade with both warring parties. Both the British and the French, however, protested the American double-dealing and established aggressive policies to limit American trade. This prompted a domestic schism as some sought the economic advantages of an alliance with the British and others supported a more ideological alliance with the liberal French. No matter the leaning, Americans everywhere nevertheless condemned both nations for violating American trade neutrality—another sovereign right of nations.

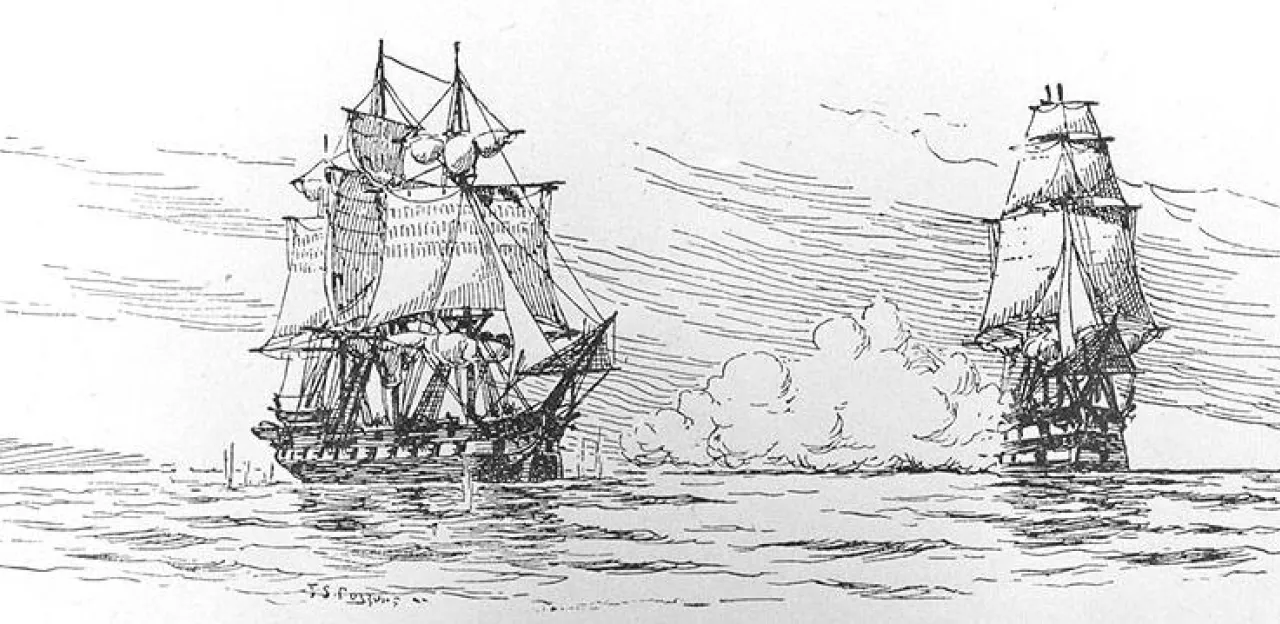

Compounding the maritime trade issue was "impressment." This was a system employed by the Royal Navy to fill its great need for sailors in its life-or-death struggle with France. At the core of the issue was citizenship. The British considered a person’s place of birth as their citizenship, while the United States considered a period of residency as their basis. This meant that the Royal Navy was at times impressing sailors that the United States considered its own citizens. Exacerbating this was the Royal Navy practice of stopping any American ship, both merchant and military, to search for deserters, British citizens, or cargo bound for France. The best example of this is the Chesapeake-Leopard Affair, when a British warship opened fire on an American frigate for refusing to stop and consent to search, resulting in four American deaths and seventeen wounded, along with four Royal Navy deserters pressed. Impressment was seen as a gross insult by Great Britain.

By 1811, “War Hawks” in the United States Congress were agitating for war with Great Britain. In June 1812, the House of Representatives voted to declare war by a margin of 79 to 49, with the Senate following 19 to 13; one of the closest votes in American history. The United States officially declared war on June 18, 1812.

Ultimately, the War of 1812 would end as a stalemate between the two countries. The United States tried, unsuccessfully, to invade Canada, and British offensives, with the exception of the burning of Washington, were likewise repulsed, spectacularly so at New Orleans. While the war had been a challenge for the United States, it had survived yet another conflict with the most powerful nation on the globe. The United States Army, despite its struggles, had been able to withstand the British, while the fledgling Navy performed better than anyone had expected, much to the surprise of Great Britain.

When peace talks were initiated in August of 1814, influenced by Napoleon’s abdication in April of 1814, the United States was able to assert its newly won national sovereignty. While the treaty did not officially end impressment or recognize American maritime rights, neither issue would trouble the relationship between the two countries again. For the British, the war had been an unwanted distraction from the crisis in Europe. For the United States, it had been a chance to prove its legitimacy as a world power. Ultimately, the only side who lost the war was the Native Americans, losing the support of Great Britain and overrun by American expansion in the next century.

Two key elements of American domestic politics arose from the war: secession and native policy. New England had suffered economically due to the loss of trade, responding with the Hartford Convention. At the Convention, secession was discussed, though never with any strength, setting a tone for political opposition throughout the next century. In addition, a number of victories over the native tribes allowed for greatly increased settlement, particularly in Florida, Georgia, and Alabama. This increased settlement would set the stage for future conflicts and the systematic relocation of native peoples throughout the nineteenth century. While the War of 1812 may not have been the United States’ “second Revolution,” it certainly helped unify and reinvigorate the nation, ushering in the “Era of Good Feelings” and Manifest Destiny.

Further Readings:

- 1812: War with America: Jon Latimer

- 1812: The War That Forged a Nation: Walter R. Borneman

- The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies: Alan Taylor

- The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict: Donald R. Hickey

- Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence: A.J. Langguth