Saida Bird: A Day in the Life of a Southern Child

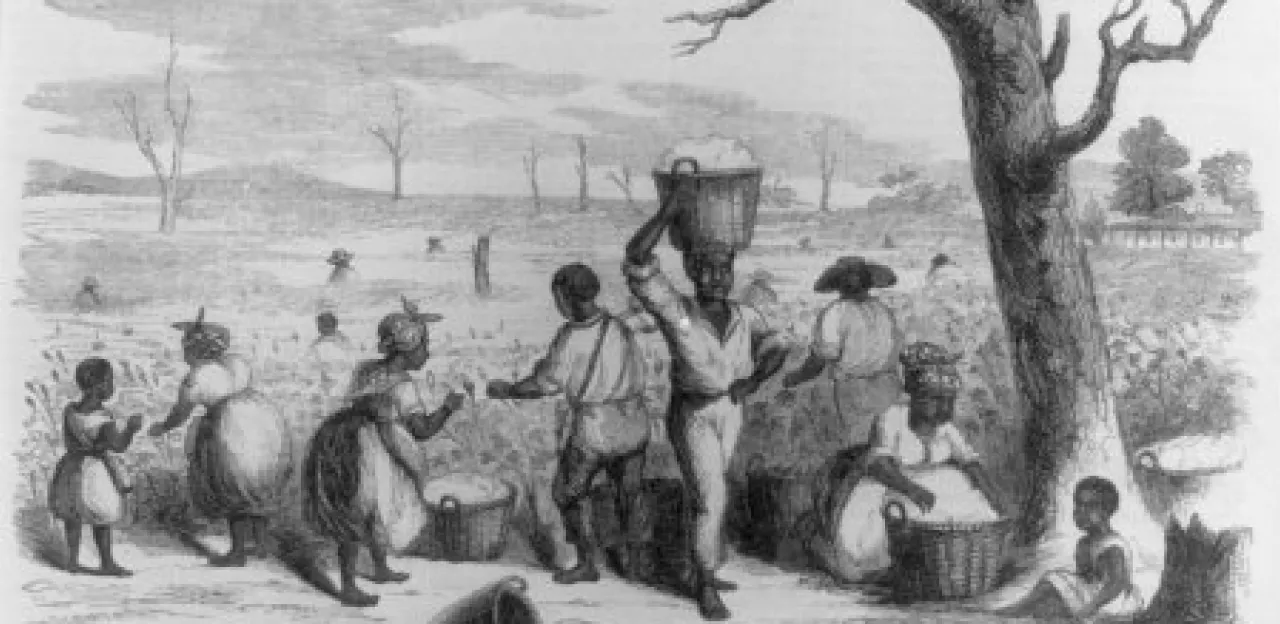

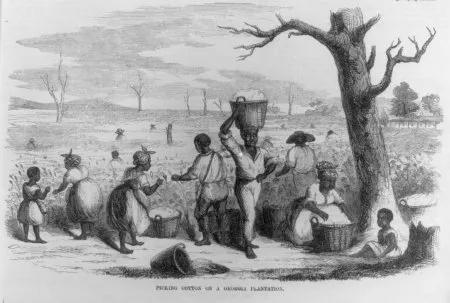

Saida Bird (her real name was Sallie) was twelve years old when the Civil War began. She was the daughter of upper-class, educated Southern parents, Sallie and Edgeworth Bird. The family owned more than forty slaves and grew cotton on their Georgia plantation. She had one younger brother, Wilson. Excerpts from the letters she wrote to her father from 1861 to 1864 show something of what life was like for a young wealthy girl in the South. However, she only rarely mentioned the domestic chores she would have been expected to do in addition to her schoolwork. Most likely, because they were routine activities and she did not feel that they would interest her father.

Voice of a Southern Child

Her mother wrote to instruct her:

I want you to read the papers and keep up with the current events. And daughter, I hope you are not idle, but busily improving your time. I want you to study and to take music lessons in Athens, if you can get a good teacher. And I do hope you will industriously avail yourself of any means of improving your mind. Remember, I wish you to read no book or novel unless with the advice and consent of a judicious friend. You might poison your young mind with improper reading. And dearest child, be faithful to your Bible and your prayers. (March 15, 1862)

It seems she was already following these instructions. In the mornings, Saida wrote to her father:

I must learn my Sunday School lesson, and besides, the breakfast bell has rung, and so I must finish after breakfast. We have had a most delicious breakfast, but I will not give you the bill of fare, for I know it would make you real hungry… (Sept. 20, 1861)

I went to Sunday School this morning, but my teacher, Mrs. Richardson, was sick and did not come, so I said my lesson to Miss Lucy. (Sept. 21, 1861)

I am going to carry some flowers to the church yard this morning. The roses are blooming here like they do in Spring. (Dec. 15, 1861)

Afternoons she would help out in the house, practice her music or study her French. Letter-writing occupied much of her time and she would take any free moments to correspond with her family and friends:

Mr. Latimer, who was discharged out of your company, came to see Mamma Saturday. I did not see him, as I was in the house helping Nancy to put up the winter curtains in the parlor. (Dec. 15, 1861)

I will take my last music lesson next Friday…Since I commenced with him [the music teacher], I have taken a piece from the opera of Martha, one from ‘La Prophete,’ one from ‘Lucretia Borgia,’ and am now taking the ‘Carnival of Venice’ and one of Goss’s Transcriptions. He is giving me the last two with ‘La Reve’ to practice during vacation. (June 21, 1863)

Je vous ecris une petite lettre Francaise que je recoive une reponse et le mets dans la lettre de Mamma, que vous voyerez que je fait des progres. (Nov. 1861)

(She wrote the letter entirely in French to show how much progress she was making.)

When I get home I intend writing to Dr. Alfriend because he was so kind to write to you...I am going to write to Cousin Sam Wiley, too, for he writes such nice letters, and I hope I will get one of them...Bud is reading The Young Voyagers, one of Mayne Reid’s books. He like’s it very much, he say’s. I believe I will read it when he gets through with it. (Sept. 20, 1861)

While her mother visited army camps, nursed the wounded in hospitals, and rolled bandages, Saida tried to help her father and the other soldiers in her own way:

I have made some sleeping caps for you and some of your men. I expect Mamma has described them to you. I have made one for you, Lieut. Culver, Mr. John Mullaly, Mr. Frank, and Wilber Little. I don’t know Mr. Wilber, but I am going to send him one because you like him, and I also have one for Cousin Sammy…(Dec. 15, 1861)

Despite the hardships of the war, Saida continued to enjoy herself in the evenings:

Cousin Eva and I walk out to the rocks almost every evening. Sometimes Martha and Cousin Sallie go. Mamma is reading Vanity Fair aloud to Cousin Sallie and Cousin Eva. She read a long time last night. Cindy made those little pallets on the floor for Cousin Eva and Cousin Sallie and myself, while Mamma was on the iron couch and read aloud. (June 21, 1863)

There was a concert here Wednesday night. I went to it and enjoyed myself finely. Miss Helen Pardee played at it, and I think she did it very nicely and prettily. (Sept. 20, 1861)

Cousin Sallie...has taught me the polka, schottisch, mazurka, and is going to teach me to waltz.

(June 21, 1863)

There was quite a large party given to Cousin Sallie in town last Friday night. She, Wilson, and myself went and had a nice time. The Saturday before we went to Mt. Zion to a dance at Cousin Jane Connell’s. Cousin Sallie met a school boy there that we, in fun, tease her about. He is the ugliest boy I ever saw in my life, but Cousin Sallie declares she is very much smitten. (June 21, 1863)

After the war, in 1866 at the age of fifteen, Saida went away to school at the Academy of the Visitation in Georgetown (Washington, D.C.) Her father died of pneumonia in 1867 and the family moved in with Sallie Bird’s mother in Athens, Georgia. Eventually, they moved to Baltimore, Maryland where Saida married Victor Smith, an attorney who was also the son of a Confederate general, in 1871. They had one son. Saida Bird Smith died in 1922.

—(Letters courtesy of the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries.)

Voice by Lynore Olsen