“Commissioning of the Continental Ship Alfred at Philadelphia, December 1775” By W. Nowland Van Powell.

“A ship without Marines is like a garment without buttons,” said Union Admiral David Dixon Porter in 1852, expressing the critical role Marines play aboard warfaring vessels. Unlike purely land- or sea-based services, the Marines’ value is in versatility, an ability to undertake specialized and cross-disciplinary missions.

These indispensable warriors entered our American story during the first year of the fight for independence. While planning for an invasion of Nova Scotia — the main British reinforcement and supply point in North America — in 1775, the Continental Congress realized the advantages that authorizing a special maritime service would provide. And so, with the goal of executing an amphibious assault on the British lifeline, John Adams penned the following resolution on November 10, 1775:

Resolved, That two Battalions of marines be raised, consisting of one Colonel, two Lieutenant Colonels, two Majors, and other officers as usual in other regiments; and that they consist of an equal number of privates with other battalions; that particular care be taken, that no persons be appointed to office, or enlisted into said Battalions, but such as are good seamen, or so acquainted with maritime affairs as to be able to serve to advantage by sea when required...

The Continental Marines’ First and Only Commandant

The first Marine officer commissioned was Samuel Nicholas, a young Philadelphia Quaker and proprietor of the Conestoga Wagon Tavern. A society man, he belonged to the exclusive Schuylkill Fishing Company — a gentlemen’s club, not a commercial fishing endeavor — and helped found the Gloucester Fox Hunting Club. Perhaps the personal recommendation of a distinguished acquaintance, coupled with some experience in the colonial merchant service, led to his selection. Regardless, Captain Nicholas’s appointment was an indicator: Philadelphia was to be the backdrop for the birth of this specialized force.

Tun Tavern: Birthplace of the Marines

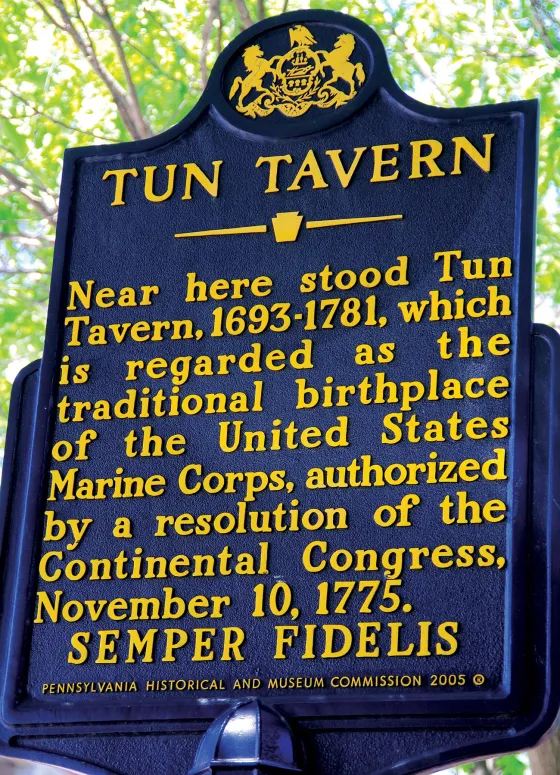

Today, at the intersection of Philadelphia’s South Front Street and Samson Walk, near the waterfront at Penn’s Landing, a marker identifies the former location of Tun Tavern, a three-story watering hole and inn commonly recognized as the birthplace of the United States Marine Corps. Originally founded by Joshua Carpenter in the late 1600s, the structure met its fair share of famous faces and is recognized by the Masonic Temple of Philadelphia as the birthplace of Masonic teachings in the country. Founding fathers like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson became acquainted with the establishment as a common meeting place for members of the First and Second Continental Congresses. Members of the Naval Committee of the Continental Congress met at Tun Tavern on several occasions to talk naval and maritime affairs, sparking the conversation about the utility of a Marine force.

The Tun Tavern was co-owned by Robert Mullan when the Continental Congress called for the formation of “two Battalions of marines” in November 1775. Mullan, an acquittance of Captain Samuel Nicholas, was commissioned as a first lieutenant of the new force. The tavern continued to serve as recruiting station for Continental Marines throughout the Revolution, although it was destroyed by fire in 1781, the same year the British surrendered at Yorktown.

The Continental Fleet and Its Flagship Alfred

Philadelphia’s waterfront was the first major shipping port in North America and, during the Revolution, it served as a vital parking lot for vessels of the fledgling Continental fleet. Among the early ships in this fleet were the Alfred, Columbus, Andrew Doria, Cabot, Providence and Fly — later joined by the Hornet and Wasp, which had been fitted out in Baltimore. Esek Hopkins was designated by the Naval Committee as commander in chief of the fleet and boarded the flagship Alfred. When the Marines received their ship assignments, Nicholas, his two lieutenants and approximately enlisted 60 Marines joined Hopkins on the Alfred.

The Alfred had an undeniable presence — so much so that she became the subject of an intricately engraved powder horn dating to 1776, carved by an H. Mack and carried by Private Isaac Chalker Ackley, both Connecticut militiamen from East Haddam. It is likely that Mack or Ackley saw the massive vessel when she visited New London, Conn. The Alfred had a white bottom, a wide black band along the waterline, vivid yellow sides, 20 9-pounder guns protruding from the lower deck gunports, 10 6-pounders on the upper deck and a figurehead of a sword-bearing, armor-clad man on her bow. While the vessel was captured by the British in 1778 and later sold off, the powder horn can still be found today in the National Museum of the Marine Corps’ Defending the New Republic Gallery in Triangle, Va.

The First Amphibious Landing

In January 1776, the Alfred — along with the Columbus, Andrew Doria, Cabot, Providence and Fly — went south from Philadelphia with the intent to “search out and attack, take or destroy all the Naval forces of our Enemies” in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay, and later destroy the British naval force in Rhode Island. But winter’s icy waters didn’t agree with that plan, and Hopkins altered the fleet’s plans to sail toward New Providence in the Bahamas to seek out gunpowder and other armaments for the bereft Continental army — but even this envisioned route wouldn’t take form until the Delaware River began to thaw in February.

Upon arrival, Hopkins hoped to take New Providence before an alarm could be sounded, but blundered by sailing the fleet past its planned landing spot and into eyeshot of the British. The island on alert, Hopkins conferred with his captains and chose to land the Marines on the more obscure eastern shore. From the Providence and two captured British sloops, Captain Samuel Nicholas and 234 Marines — boosted by the support of 50 sailors — carried out the Continental Marines’ first amphibious landing on March 3, 1776. The hybrid force landed unopposed, captured New Providence and seized its two forts. While the island’s Governor Browne snuck more than 150 barrels of gunpowder out before the American landing, the Continental force still procured numerous brass cannons and mortars for George Washington’s army, foreshadowing the Marines’ success in Revolutionary raids to come.

The First Land Combat

In late December 1776, the Marines found themselves not at sea, but on a river, ready to assist Washington in his planned crossing of the Delaware. Although not engaged at Trenton, they joined the main force near Trenton on the night of January 2, 1777. Attached to General Greene’s Division, they were initially placed in reserve for the next day’s battle at Princeton, but the approximately 130 Marines were called into action at a critical moment. Advancing on the right flank, they managed to slow the British advance, but began to falter under intense fire. Reinforced by timely arrivals and rallied by Washington himself, the Marines recorded their first land action — and victory.

Upon the Revolution’s end with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the Continental Marines were disbanded — and out of approximately 130 Marine officers and 2,000 enlistees, only 49 were lost in the fight for independence. But the powerful group wouldn’t be gone for long. On July 11, 1798, President John Adams — the man who penned the resolution to establish the Continental Marines — signed a congressional act into law, creating the United States Marine Corps.

To learn more about the fascinating development of this branch of the United States military, check out all that the National Museum of the Marine Corps has to offer at www.usmcmuseum.com.