Philadelphia during the Civil War

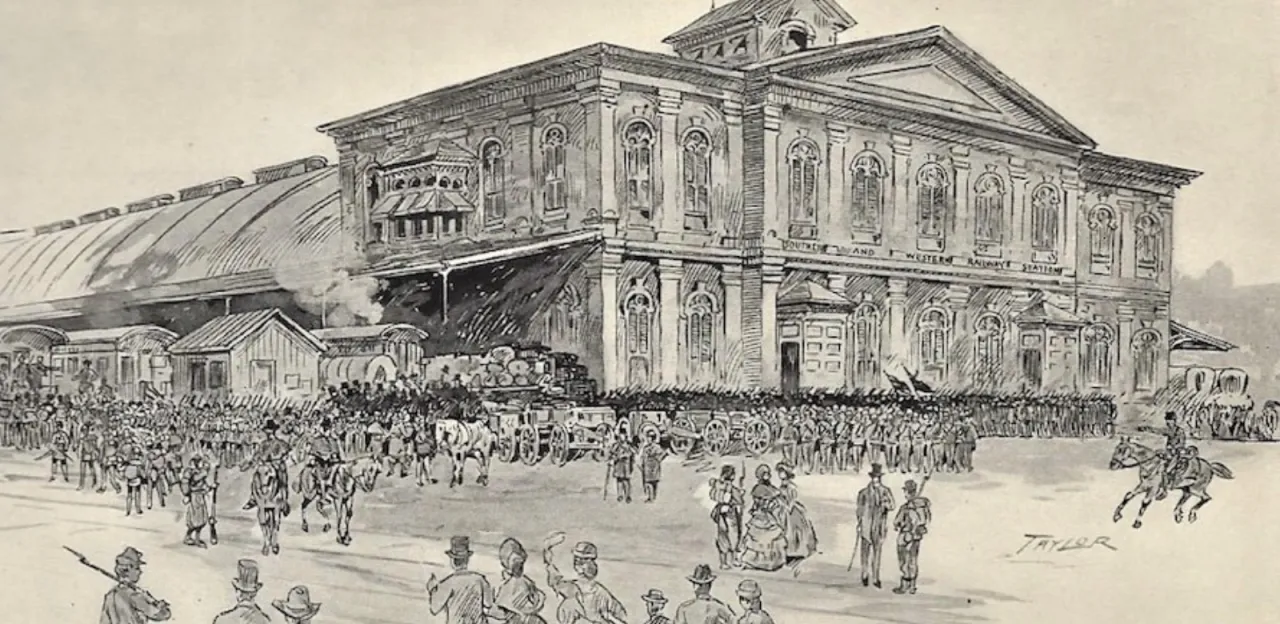

Though the city of Philadelphia had many important economic ties to the South, its citizens were quick to take up the Union cause against those states that seceded. Throughout the war, Philadelphia provided many resources for the Union war effort, but perhaps the most important resource it sent was its citizens who served as soldiers in the Union Army. Almost 100,000 Philadelphians served in the Union Army between 1861 and 1865, which was about three quarters of the city’s male population. Many of these troops were raised right from the outset; April of 1861 saw the creation of eight infantry regiments. 1862 saw an even greater rush of volunteers, so much so that they postponed a draft for the city. The majority of these soldiers were native-born citizens and from the city’s immigrant population. A large portion of Philadelphia's freed African-American population, after some debate, also offered to take up arms, but like all other black volunteers from Union states, they were initially denied service. In addition, some of the most famous figures of the war, such as Generals George McClellan and George Meade, were natives of Philadelphia.

The infrastructure of the city was also converted to bolster the Union war effort. Less than thirty miles from the city lay Phoenix Ironworks, a foundry that became one of the most productive Union munition plants in the country. At its peak, the factory could produce around 50 rifled artillery pieces a week, and produced several thousand cannon for the Union war effort. Interestingly, the city was also home to one of the nation’s largest military hospitals during the war. In addition to healing troops, or as well as they could at the time, the doctors who worked on the wounded were often prone to frequent experimentation, trying out new medicines, new technologies and new methods of transporting the wounded without risking more lives. When black soldiers entered the Union army, many doctors also took the chance to “prove” physiological differences between the former and their white compatriots.

For civilians, life during the war meant carrying on as normally as possible, but many people kept a keen interest in developing news and participating in whatever way they could. The women of Philadelphia often led the charge on this front. They organized and ran frequent donation drives, through which they provided whatever spare materials they could to soldiers on the war front in need. Organizations like the United States Christian Commission also played a major role in delivering donated goods to soldiers. Many were obviously awaited news of their friends and family members who had gone to fight, and mourned deeply when they heard the worst, but others still eagerly awaited and celebrated news of Union victories. The struggle to walk the line between is a prominent theme in the private diaries of locals, like that of Emilie Davis, a free working-class African American woman. Church sermons also frequently crossed the boundaries between spiritual and political matters. In one particularly fiery speech by Wilbur F. Paddock, he states, "By withholding success to our arms, God has as it were forced upon us the attempt to remedy a grievous wrong, to remove the foul blot upon our national escutcheon, which has for so long disgraced us in the eyes of the civilized world.” The grievous wrong he refers to is slavery, and indeed, sympathy for slavery dropped steadily in the once-moderate city as the war went on. This coincided with the rise in support for Republican Party politics over the previously favored Democrats.

During the Civil War, the citizens and other residents of Philadelphia, both soldiers and civilians, made enormous sacrifices to bring victory for the Union. The various records and writings made by the people there offers us an important glimpse into civilian and military life.