"His Majesty George III Resuming Power" by Benjamin West

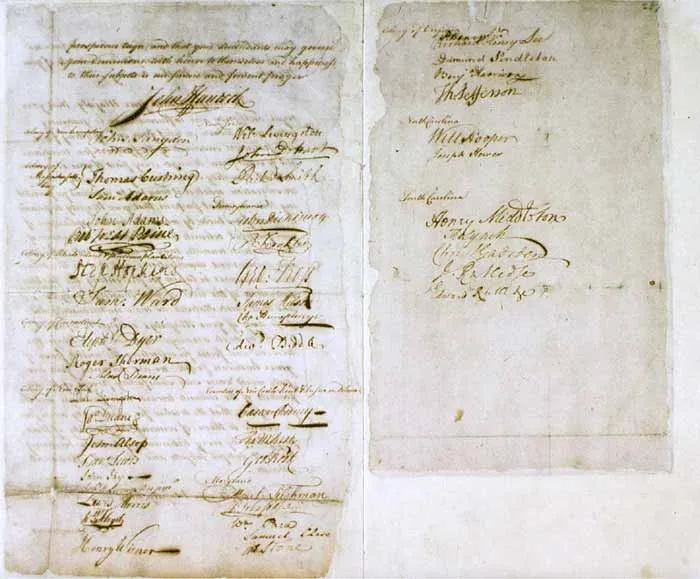

“We, your Majesty’s faithful subjects…” read the opening line of the July 5, 1775, petition by the Second Continental Congress to King George III of England. Remembered in American history as the “Olive Branch Petition,” the document was the last plea for moderates among the delegates assembled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in a hope to speak directly to the king. The goal was to seek the royal’s help in breaching the fissure that had erupted between Britain’s American colonies and the mother country. Months later, the reply informed the Continental Congress that the king had rejected the petition outright and in fact, refused to even lay eyes on the document.

The “Olive Branch” name is traditionally regarded as a symbol of peace, drawn from the biblical story of Noah in the book of Genesis. In July 1775, this was the last-ditch effort to prevent formal war and rupture with Great Britain after the fighting at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts the previous April and the more recent skirmish at Bunker Hill outside Boston in late June. Twelve colonies—all except Georgia which had declined to send representation to the First Continental Congress—signed off on the sending of the document, which had been drafted by John Dickinson. With wording such as “tender regard,” the delegates insisted the colonists remained “faithful subjects” to “our Mother country.”

King George III’s response, alluded to above, was adamant regarding the situation in North America, describing it as “various disorderly acts committed in disturbance of the publick peace, to the obstruction of lawful commerce, and to the oppression of our loyal subjects.” The monarch viewed the 13 seaboard colonies as being in a state of “open rebellion” and ended his response with the steps his government was in the process of taking to suppress the rebellion. This attempt, crafted by moderates, failed. The fate of the 13 colonies was to be decided on the field of battle.

Prior to the “Olive Branch Petition,” the First Continental Congress, convened on September 5, 1774 through October 26, 1774, met in Carpenter Hall in Philadelphia. The reason for calling delegates from the colonies to meet was to find the best avenue to address their complaints regarding the current acts passed by the British Parliament and how to convey a response to that body politic. At this juncture of time, when the First Continental Congress came into session, delegates with loyalist or pro-British sentiment outnumbered those favoring rebellion and independence from Great Britain. During the 13-month congress, the discussions centered around forcing the British Parliament to rescind acts the colonials found repulsive and unreasonable and to seek out resolutions that would lead toward reconciliation. Others viewed the gathering of delegates from 12 of the 13 colonies with the goal of developing a rubric of rights and liberties and issuing a unifying statement that publicized that stance. Both sides wanted an end to the abuses the colonies had suffered under the various acts passed by Parliament, as well as a retention of their rights under the English constitution and their respective colonial charters.

The First Continental Congress managed to get consensus on the Continental Association and a Declaration and Resolves. The former called for a universal boycott of all British goods by the colonies as a form of economic sanctions to force Parliament’s hand; Parliament needed to acknowledge the colonies’ grievances and rescind acts that were leading to further disagreement. A portion of the text, which in its entirety laid out 14 points of action, reconfirmed the stance of the First Continental Congress and its commitment to staying in the British Empire, is below:

We, his majesty’s most loyal subjects, the delegates of the several colonies…avowing our allegiance to his majesty, our affection and regard for our fellow-subjects in Great Britain and elsewhere, affected with deepest anxiety, and most alarming apprehensions, at those grievances and distresses, with which his Majesty's American subjects are oppressed; and having taken under our most serious deliberation, the state of the whole continent, find, that the present unhappy situation of our affairs is occasioned by a ruinous system of colony administration, adopted by the British ministry about the year 1763, evidently calculated for enslaving these colonies, and, with them, the British Empire…

Secondly, the Declaration and Resolves was the First Continental Congress’s response to the Intolerable Acts—the Coercive Acts by Parliament—and their passage in 1774. Congress outlined its objections to the acts, included a bill of rights from the colonial representation, and then listed out specific objections that the delegates had. Every colony, besides New York, eventually approved the resolutions of the First Continental Congress. If no action by Great Britain was taken, the First Continental Congress voted to convene again in one year’s time.

The powers in Great Britain—Parliament and King George III—viewed the First Continental Congress and the Continental Association that body created as illegal gatherings. The actions agreed upon by the First Continental Congress though, created reverberations within British trade, affecting merchants and their companies. Though pressured to find a solution to this interruption in trade and the economy, Parliament resisted and did not repeal the Coercive Acts.

Between the sending of the Continental Association resolves in September 1774 and the “Olive Branch Petition” in the summer of 1775, events in the colonies hastened the crumbling of the relationship between the colonies in North America and Great Britain. With the actions of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, followed by the battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, which led to bloodshed of colonials and British soldiers, the chance for peace decreased. However, many in the First Continental Congress still believed that the issue was solely with the British Parliament and that the king of England was still sympathetic to his colonial subjects. When King George III, the supposed friend of the American colonists, refused to even look at the “Olive Branch Petition,” the time for petitioning peacefully had passed. Within a year, the American colonies, with representative delegates assembled again in Philadelphia—this time down the street from where the First Continental Congress convened—resolved to pass the Declaration of Independence. The die was cast.

“We, your Majesty’s faithful subjects…” became “We, therefore, the Representatives of the United States of America.”

Related Battles

93

300

450

1,054