Nothing but God Almighty Can Save that Fort

By James R. Knight

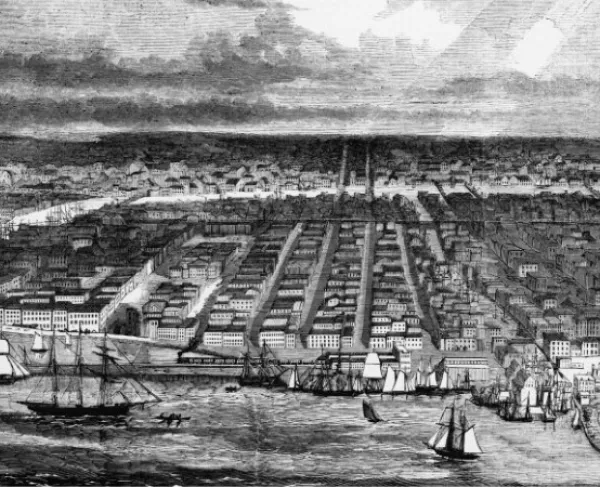

When the commanding general of the Federal army’s first major offensive began loading his troops onto riverboats at Cairo, Ill., on February 2, 1862, few in the North had even heard his name. Four days later, seven of his gunboats, under the command of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, opened fire on the Confederate garrison at Fort Henry, on the Tennessee River. The fort, eight months in the building, surrendered just one hour later.

Within the next 48 hours, the Federal navy severed the main Confederate rail link to West Tennessee and Kentucky and docked two gunboats at Florence, Ala., 125 air-miles behind the enemy lines. The Tennessee was now a Federal river, and from the message dispatched to department headquarters in St. Louis, Mo., it is clear that this failed merchant turned soldier planned to make short work of Fort Donelson and the Cumberland River as well.

Headquarters District of Cairo,

Fort Henry, February 6, 1862

Fort Henry is ours. The gunboats silenced the batteries before the investment was completed. I think the garrison must have commenced the retreat last night. Our cavalry followed, finding two guns abandoned in the retreat. I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry. — U.S. GRANT, Brigadier-General.

New to a command of this size and type, and unfamiliar with the wilds of northern Tennessee in the dead of winter, Grant soon realized that his timeline was much too optimistic. Between incessant rain and the flooded Tennessee River, it took him six days, instead of the anticipated two, to move his army the 12 miles between the two forts. But on the chilly evening of February 12, he established his headquarters in the small home of a widow named Crisp, a mile from the Cumberland River.

After a week of rain, the final day of marching was clear and mild and, except for a skirmish with Confederate cavalry — led by another virtual unknown, Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest — the journey had been uneventful. One of the Union gunboats, USS Carondelet, had steamed up the Cumberland River and fired a few shells towards the fort, feeling out the enemy batteries and serving notice that the Navy had arrived.

Had Grant fulfilled his boast and arrived at Fort Donelson with his 15,000 men on February 8, he would have found the fort defended by 7,000 disorganized Confederates unprepared to face a Union army twice its size. The four extra days had made a big difference.

Word of the fall of Fort Henry had reached Confederate headquarters at Bowling Green, Ky., on the afternoon of February 7, prompting an emergency meeting of the Department commander, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston; his newly arrived deputy, Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard; and Maj. Gen. William Hardee, commander of the troops in central Kentucky. With Fort Henry and the Tennessee River in Union hands, they acknowledged that Fort Donelson was an untenable position and concluded that the entire southern Kentucky defensive must be abandoned and a new line formed south of the Cumberland River. Worse still, Columbus, Ky., the large Confederate base on the Mississippi River was outflanked.

Ironically, with the eventual loss of Fort Donelson now a foregone conclusion, its immediate reinforcement became the top priority for Johnston. Unless the position was held for at least another week, Union gunboats might steam up the river, block its crossings and trap the Confederate army. Albert Sidney Johnston would personally supervise the withdrawal from central Kentucky and ordered some 10,000 additional troops and tons of supplies and munitions to be sent to Fort Donelson.

The Confederates inside Fort Donelson were unaware of these strategic developments but had already begun preparing their defenses for the coming onslaught. Maj. Jeremy Gilmer, the Department’s chief engineer, had seen the gunboats first hand at Fort Henry and pushed the work on the outer defensive line, while Capt. Joseph Dixon concentrated on the upper and lower water batteries, mounting heavy guns and training infantrymen to man them. During the delay, the Confederates worked around the clock, expanding the outer works to enclose not only the fort and its batteries on the river, but also the town of Dover, about a mile distant, and its vital steamboat landing. By the time Grant arrived, reinforcements had ballooned the Southern garrison to as many as 17,000 soldiers.

As Grant and his staff settled in before the Widow Crisp’s fire, his army fell into position opposite the Confederate line, about a half-mile in advance of the fort itself and the water batteries guarding the Cumberland River. On the right, Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, tried to stretch his line far enough south to cover the roads out of Dover, but discovered he was undermanned. On the left, Brig. Gen. Charles F. Smith took up position along a ridge line and across a small valley.

Grant’s division commanders were a study in contrasts. John Alexander McClernand was an Illinois congressman with a distinct personal agenda that would eventually see him relieved of command for insubordination. Charles Ferguson Smith, however, was a professional soldier and West Point graduate who had served as the Commandant of Cadets during Grant’s years at the academy. After 36 years in uniform, he found himself serving under a former student but, by all accounts, gave Grant his complete support.

As his army settled in, Grant ordered that no major engagement should be provoked, as substantial reinforcements made their way up the Cumberland with a large naval convoy. Both sides, however, faced the same enemy in the weather. As the pleasant day turned into a cold night, with a north wind that brought first rain and then sleet, Federal troops who had been ordered to drop their knapsacks, overcoats and blankets in the rear as they went into line, shivering on the hillsides. The Confederates fared little better, as it was feared that fires would provide targets for snipers and artillery.

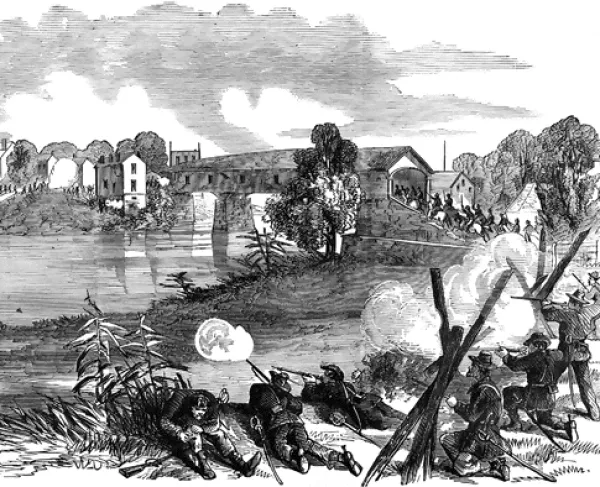

Thursday, February 13, 1862, dawned bright and clear. While Grant’s order not to bring on a general engagement was still in effect, sniping soon became common all along the line. Some such “reconnaissance in force” ended badly, including one instigated by the commander himself. The ironclad gunboat USS Carondelet, under Cdr. Henry Walke, had lobbed a few shells at Fort Donelson the previous day, but now Grant had a more strategic use in mind — creating a diversion as Smith probed the strength of Confederate defenses. Around 10:00 a.m., from a distance of a mile and a half, Carondelet opened fire and the reconnaissance force set off across the valley up the slope beyond, led by the green men of the 25th Indiana. Louis D. Payne of the 2nd Kentucky, a part of the Confederate unit that would later earn fame as the “Orphan Brigade,” recalled the position of the Southerners waiting in the rifle pits:

We were armed with old flintlock guns, loading with three small and one large ball, very deadly but not carrying far…Col. Hanson…sent this order to each of our captains: ‘Let no man fire until I give the word.’ It seemed as if the word would never come. The Yankees were almost upon us…Then we were allowed to turn our guns loose. We could see the enemy falling… ‘Keep it up!’ cried our captains…and we did.

As the Kentuckians poured down the “buck and ball” from those old flintlocks, a nearby Confederate battery swept the hillside with case and canister, stopping the raw recruits cold as it pinned them down in the brush and slowed their retreat to a crawl.

To the south, McClernand continued stretching his line to surround Dover, but came under fire from a battery of guns under Capt. Frank Maney and supported by an infantry brigade. McClernand called in counter-battery fire and then sent in four infantry regiments of his own. The artillerymen took a beating, but stood fast and Heiman’s infantry turned back the Union assault. All the while, the Carondelet rained fire on the fort and the water batteries — 184 rounds in all, only one of which caused any real damage. Near the end of the bombardment, a 24-pounder in the lower water battery was struck and dismounted. Capt. Joseph Dixon, who had masterminded the defensive position, was struck by in the head by flying debris and killed instantly. He was the only casualty.

By the end of the second day, it was clear that long-range shelling from the river would not disable the fort or the water batteries. Moreover, it was evident that the Confederate defensive line was formidable and that more troops were necessary if the Federal army was to block all the roads into Dover. Accordingly, Grant sent orders for reinforcements back to Fort Henry and the majority of the remaining garrison soon set out under command of Brig. Gen. Lewis Wallace, a politician from Indiana overjoyed by the prospect of battlefield glory.

That night the weather worsened — rain and sleet followed by three inches of snow. Late that evening, gunboats carrying several fresh regiments arrived on the scene, and Grant insisted Flag Officer Foote attack the next day, despite the latter’s misgivings. After two nights of brutal weather, the Federal commander feared a prolonged siege, with his army living in the open, and hoped that his Brown Water Navy would carry the day.

On the Confederate side, Brig. Gen John B. Floyd had arrived to take overall command, with Gideon Pillow overseeing the left wing, Simon B. Buckner the right and Nathan Bedford Forrest in charge of the cavalry. As the snow and sleet swirled outside, the Confederate officers met to discuss their options. They agreed that Grant was being strongly reinforced, although they overestimated his strength, and determined that their only course of action was to break out before the Federal force grew any stronger. As early as possible the following morning, they would overload the left flank and Pillow would lead a force out to against the Union right and, theoretically, open the roads to Nashville. Buckner’s men from the right would shift to the center and then act as the rear guard, holding the roads open until the rest had escaped.

The next morning, Grant told his command to be ready to exploit what he assumed would be a great gunboat victory, like the one at Fort Henry. Foote was to reduce the fort and water batteries, while running at least one gunboat past the batteries to capture the landing at Dover and cut off the Confederate’s last source of supply and escape. Ultimately, McClernand would advance against what was expected to be a demoralized Confederate infantry and take the town.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, Pillow’s troops formed so slowly that it was 1:00 p.m. before the assault began and the column went only 400 yards before halting, countermarching and calling off the attack. But if no Confederate infantry attack materialized, neither did a Union ground offensive; all the action was at the river.

Just before 3:00 p.m., Flag Officer Foote brought his six gunboats to within a mile of the water batteries and opened fire. Watching the smoke and flame from the river, Floyd sent a stream of telegrams to Gen. Johnston and predicted the fort could hold for perhaps 20 minutes. Forrest, astride his horse in a nearby ravine turned to Maj. David C. Kelly, a Methodist minister, and exhorted him, “Parson, for God’s sake, pray! Nothing but God Almighty can save that fort.”

In the besieged water batteries, the reality was less dire. Although the bombardment looked fearsome, most Federal rounds either went high or plowed up dirt, inflicting little damage. Meanwhile the Confederates gunners were only firing with two long range guns — a 10-inch Columbiad and a 6.5-inch rifle. But once the gunboats closed to within about 400 yards of the lower water battery — practically point-blank range for artillery — the Southerners opened fire with seven additional 32-pound guns.

One Confederate was heard to shout, “Come on you cowardly scoundrels. You aren’t at Ft. Henry!” And it was true; fired from above, the solid shot plunged through the supposedly invulnerable gunboats’ unprotected wooden decks, battering their superstructure and leaving them holed below the waterline. One by one, they broke off the fight and floated back down the river to huge cheers all along the Confederate line.

That night, the Confederate commanders met again. While the repulse of the Union gunboats had been a tremendous morale boost, it did not change their basic situation. Northern reinforcements continued to arrive and if the Confederates did not break out of the Union encirclement, it was just a matter of time before they would be overwhelmed. The council of war agreed to again attempt the previous day’s aborted breakout at first light.

At sunrise on February 15, Grant and some of his staff left the Widow Crisp’s house, travelling downstream to confer with Flag Officer Foote, who had been wounded during the previous engagement, and survey the damaged navy. As they departed they heard small arms fire far to the south, but were not alarmed by it. Grant himself later said: “When I left ... to visit Flag Officer Foote, I had no idea there would be any engagement on land unless I brought it on myself ... The enemy, however, had taken the initiative.”

This second Confederate attack was much better organized. Just after sun-up, Pillow emerged with 14 regiments and smashed into the right flank of McClernand’s division. A Union brigade under Col. John McArthur that had been ordered to the small rise known as Dudley’s Hill the previous evening awoke under fire as they, together with Col. Richard Oglesby’s brigade, bore the brunt of the Confederate attack, even as they were harassed by Forrest’s cavalry sweeping around the flank.

By mid-morning, the Union right was in trouble, as McClernand sent several urgent message to headquarters requesting reinforcements. But Grant had left, and no staff officer was willing to take responsibility for allocating troops. Finally, McClerand appealed directly to Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace, who had arrived with reinforcements — freshly deemed the 3rd Division — the previous day. Wallace dispatched a brigade, but it was not enough to turn the tide. By noon, the right wing of the Federal line had been smashed and rolled back, with whole regiments out of ammunition. Eventually, Wallace — a division commander for all of 18 hours — formed his nine remaining regiments into a line and threw back three separate Confederate assaults.

Gideon Pillow’s breakthrough had ground to a halt by 2:00 p.m., but not before he had opened the road to Charlotte and Nashville, giving the Confederate’s their escape route. Inexplicably, however, he ordered his men to fall back inside their original lines. When his furious commander, Brig. Gen. John Floyd, met Pillow returning from the field, he demanded: “In the name of God, General Pillow, what have we been fighting all day for? Certainly not to show our powers but solely to secure the Wynn’s Ferry Road, and after securing it, you order it given up!”

Meanwhile, Grant had returned to the scene. The moment he came ashore from Foote’s flagship, he was appraised of the situation and hurried upstream as fast as the icy roads would permit. Displaying the audacity for which he would become legendary, Grant refused to assume a defensive position, telling an aide, “The one who attacks first now will be victorious, and the enemy will have to hurry if he gets ahead of me.” He ordered the men to refill their cartridge boxes and reform their units. McClernand and Wallace moved forward into the void left by Pillow’s withdrawal, ordered to retake the roads as soon as possible. Grant also had plans for Gen. Smith and his men on the north part of the line, who had been idle all morning.

Grant found his old teacher sitting under a tree, waiting for orders. Believing that the Confederates must have weakened their line in front of Smith’s division in order to mount such a devastating attack from their left flank, Grant told Smith, “All has failed on the right. You must take Fort Donelson.” Charles Ferguson Smith had been waiting his whole professional life for a chance like this, and moved quickly, vowing to lead the assault personally.

The terrain before Smith’s division was rugged in the extreme — after the war, Wallace recalled his men saying it “looked too thick for a rabbit to get through” the brush — descending and ascending steeply. The first troops through came from the 2nd Iowa, with Smith among them, bellowing: “Damn you, gentlemen, I see skulkers. I’ll have none here…. Come on, you volunteers! This is your chance. You volunteered to be killed for love of country, and now you can be!”

Grant’s assessment of Confederate strength was entirely accurate. Whereas on the previous day, the line had been held by Simon Buckner’s entire 3,800 man division, now only 450 men from the 30th Tennessee remained. Overwhelmed, they fled their rifle pits and fell back to the last ridge line between then and the fort, where they were reinforced by elements of Buckner’s command returning from Pillow’s abandoned charge. As night fell, Smith settled into the 30th Tennessee’s abandoned works, assuming that in the morning, his forces would move on the final ridgeline; once the Yankees had artillery on those heights, they could pound the fort and the water batteries into rubble at their leisure.

Inside Southern lines, the mood was far less hopeful. The room was rife with recriminations as the three senior Confederate officers met in the town of Dover, discussing options following Pillow’s disastrous order to withdraw after securing the road out of town. Pillow himself wanted to stay and fight another day, but was dismissed by Buckner — who refused to sacrifice more men when the outcome was no longer in doubt. The possibility of marching out through the darkness was discussed, but the weather made it impossible. Marching through snow and flooded roads might mean the loss of three-quarters of the men in the process of escape.

In the end, surrender was deemed the only humane option. Even though they agreed, with the decision, both John B. Floyd and Gideon Pillow refused to participate in the exercise and resigned their commands in order to escape. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who strongly disagreed with the decision, was told that he could leave with as many of his cavaliers as would follow him; about 500 mounted men left by the partially flooded River Road without firing a shot. In the end, although he had been third in seniority, it was left to Simon B. Buckner to surrender Fort Donelson and the Confederate army to his old friend and West Point upperclassman.

Before dawn on February 16, Maj. Nathaniel F. Cheairs of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry carried Buckner’s request to discuss surrender terms across the lines and was escorted to Grant’s headquarters by Brig. Gen. Smith, who warmed himself by the fire as his commander read the note. Grant then handed the missive to Smith, asking his opinion. Smith replied curtly, “No terms to the damned rebels!” and Grant penned the brief reply that transformed him into a legend:

... No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.

Maj. Cheairs took the note back and returned with Buckner’s reply, reluctantly accepting what he called Grant’s “ungenerous and unchivalrous terms,” and the battle for Ft. Donelson was over.