By: Adam E. Zielinski

Despite early hopes for a quick victory, the rebellion in the North American colonies had not been suppressed by the end of 1775. British strategy for winning the war struggled to gain coherence. Running a war from across the Atlantic Ocean was difficult for Secretary of State for North America George Germain. By the time his orders reached British commanders in America, the situation sometimes changed and the orders were outdated. Thus, the generals on the ground themselves often felt compelled to issue their own orders over those of Parliament.

British commander William Howe had chased Washington and the main body of the Continental army from New York and across New Jersey in 1776, only to suffer embarrassing losses at Trenton and Princeton. As the campaigns of 1777 took shape, Howe had his eye on Philadelphia: the rebel capital. This made sense in some regards. Philadelphia, along with Boston, New York, and Charleston, was one of the largest ports in the colonies. Geographically centered in North America, if it were to fall in British hands, it could prove to be a decisive stroke that psychologically destroyed the rebellion. Howe became convinced, perhaps even so at the chance for personal glory, that capturing Philadelphia was a priority.

Howe's desire to capture Philadelphia jeopardized the British strategy for the war. One of the primary directives was to hold the Hudson River (which is the reason why New York City was such a valuable prize). If the British could control both the northern and southern entry points to the river and provide threatening pressure on the waterway in the American interior, they could potentially cut off New England from the remaining colonies. This would isolate Massachusetts and, the British hoped, extinguish the rebellion.

The Americans were aware of this strategy. Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York had been a crucial point for both British and American armies. American forces seized the fort and its precious artillery pieces in 1775. They transported the guns to Boston to blast the British from the city. The Continental Congress had also supported an invasion of British Canada, hoping that an insurrection would lead Canadians to support overthrowing their British authorities. This proved badly misjudged, and the British successfully ended any American threat to Canada. Remaining in control of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Champlain, British forces plotted to use the Hudson River to their advantage. In 1777, they planned to link a portion of Howe’s army in New York City with that of Gen. John Burgoyne, whose forces were marching south from Lake Champlain. Howe, instead, kept his forces together to take Philadelphia. This decision by Howe had major consequences for the events in 1777.

Without Howe to support him, Burgoyne had to rely on the forces under his command. By July 1777, his army consisted of a mixture of British regulars, Hessian mixed units, and Native American allies, totaling about 8,000 troops. Burgoyne was successful in driving the Americans out of their northern fortifications, including Fort Ticonderoga, in July, and then again at the Battle of Hubbardton, Vermont, on July 7. Following the dual victories, his forces stopped to regroup.

In the coming weeks, trekking through the American interior proved dire to the health of his army. Critical supplies such as wagons, food, and most of all, horses, began to wear thin. The retreating Americans had sabotaged the roads, and it became apparent that if he could not find a depot to raid or receive supplies from the British on the Hudson River, Burgoyne’s army could very well disintegrate before they reached Albany, New York.

As this was happening, Col. John Stark was busy making trouble with orders he’d received from the Continental Congress. Stark, a veteran of Bunker Hill and the New Jersey victories, who’d commanded the New Hampshire Line, was sent back north to recruit more soldiers at Washington’s request. However, he soon learned that he had been passed over for promotion for an officer he deemed incompetent. He abruptly resigned from the Continental army. New Hampshire then offered him a commission as a brigadier general militia, which Stark agreed to under one condition: he would not take orders from any officer in the Continental army. The first test of this "condition" occurred when American Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln found Stark and ordered his troops to Albany in support of Philip Schuyler. Stark refused and remained guarding the countryside north of Albany. Hundreds of regional militia flocked to the popular Stark. Within six days, he had raised a force of 1,500 men.

In the meantime, Burgoyne’s army was running out of gas. He badly needed supplies and horses for his cavalry, which were now on foot. Intelligence detected possible stores in the nearby vicinity of Manchester, Vermont. On August 4, Burgoyne gave orders to his subordinate, Baron Riedesel, to prepare a detachment to descend on Manchester. Riedesel protested the orders. The country was far too vast and full of hostile rebels. Without knowing how many rebels they were facing, it seemed ludicrous to send a small force out that may have to engage in a major battle. Burgoyne had to decide whether to send a raiding party or a large enough detachment that could combat any American force they confronted. After receiving new reports from local spies, Burgoyne then changed his mind, and ordered a detachment to make for Bennington, Vermont, where it was thought a large rebel supply depot was being guarded by the remnants of the small American force defeated at Hubbardton. Burgoyne sent Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum with about 600 troops to raid the depot at Bennington and remove the threat of any lingering Americans.

Leaving Fort Edward on August 9, Baum assembled mixed units of Hessian light infantry, about 100 Native American fighters, an artillery regiment with two field pieces, and hundreds of Tories (American Loyalists) picked up en route. All told he had about 800 - 1,000 men under his command. Baum marched deliberately and had the regiment musicians play marching tunes during their journey.

After ironing out his independent command, and quite aware of the dangers Burgoyne’s presence was to the region, Stark arrived with his militia of 1,500 troops in Bennington, unaware of Baum’s approach. He had intended to link up with other Americans in Manchester but broke with orders again and decided to camp at Bennington. Upon learning of the actual numbers of rebels guarding Bennington from deserters, the Hessian commander sent word off to Burgoyne that the depot was not guarded by a few hundred Americans, but by nearly 1,800 soldiers. A reconnaissance detachment under the command of Continental Lieutenant Colonel William Gregg met Baum’s advance guard on August 13. The Americans fired a few shots and destroyed a bridge before retreating back toward Bennington. Baum pursued.

The American army that awaited in Bennington was hardly an army at all. Most of Stark’s men were farmers and locals who had literally grabbed their powder horns and rifles from their houses and fell in with Stark's command. Stark remarked that most of his men wore colorful civilian dress and hardly looked like a professional army. They had little time to prepare for the enemy force heading their way.

Baum reached the outskirts of Bennington on August 14 and began assembling breastworks on a hill northwest of the town. Skirmishes and quick volley exchanges broke out during the day. Several Native Americans were wounded or killed, prompting the remaining fighters to threaten abandoning the whole operation. Caution reigned over the British encampment that evening. The following morning, August 15, a sudden rainstorm halted any further advances toward the depot.

Baum had his forces spread out mainly north of Bennington. The breastworks had become a redoubt made of logs and timber, housing the dragoons under Captain Alexander Fraser. Light infantry covered the lower ground near the Walloomsac River while about sixty troopers guarded the two three-pounder cannons on the raised hillside. The remaining bulk of Baum’s forces watched over the main road and bridge, a mixture of British sharpshooters and Hessian jägers (pronounced “Yay-gers”), known as Brunswickers. Another redoubt was positioned east of the Walloomsac River. The last of the forces guarded the baggage and stolen goods from colonial farms and houses. Apparently a great many of the Native American fighters were seen to be lingering in the rear to protect their loot.

As he waited, Baum received orders from Burgoyne that he could expect reinforcements within a day or two. In the meantime, the decision to attack or to withdrawal rested on Baum’s judgment. Burgoyne ordered Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Breymann to reinforce Baum. The decision was not without its curiosities. Breymann and Baum had apparently been rivals and were not known to hold a high opinion of each other. Breymann was also a notoriously slow marcher. Breymann's march was tempered with miserable road and terrain conditions.

The morning of August 16 brought a break in the clouds, and it was precisely the moment Stark had been planning for. Having gathered enough intelligence on Baum’s positions, Stark decided to split his forces into three separate divisions. Stark devised if he could attack Baum simultaneously with all three of his divisions, it might be enough to overwhelm them. One detachment would break off and go around the Hessian left flank while another would march south and swing around to the enemy’s rear. Another detachment would storm the loyalist redoubt. Stark led the remaining Americans in an assault on the British center. His plan depended upon a combined execution of timing, precision, and luck. As the Americans were about to get underway, Stark gave a speech to his men. What was said is not known; however, almost every story to follow undeniably has him proclaiming, “There are the redcoats and they are ours, or Molly Stark sleeps a widow tonight!”

At 3 pm, Stark’s three divisions made their move. The initial advance startled the Hessian scouts, who promptly fell back toward the redoubts. An intense firefight broke out that Stark later said was “the hottest engagement I have ever witnessed.” While the assault was underway, Lieutenant Colonel Moses Nichols led his division to the left of the redoubt north of the Walloomsac River. Baum mistakenly thought these men were abandoning the field from the intensity of the fight. As the battle proceeded, Baum saw these men approaching from the north, and seeing that they were dressed in civilian clothing, mistakenly took them to be loyalists. The Americans reached the redoubts and opened fire at close range, completely overwhelming the Hessian and British defenses.

Meanwhile, the American southerly detachment under the command of Colonel Samuel Herrick crossed the river from the east and made their way west below the Tory redoubt. They then crossed the winding Walloomsac’s again and came up directly behind both the Tory and dragoon redoubts. The overwhelming onslaught of Stark’s men drove Baum’s forces from their positions. What fight Baum’s men put up was quickly doused by superior numbers. Close quarters fighting muddied the redoubts. The cannons fell silent. A disorganized and scattered retreat came over the mixed troops. American sharpshooters and militia fired at anything that was running away from them. Many troops were slowed by their uniforms and packs—much heavier and tiresome compared with the civilian wear of the militia. Others made it through the trees and brush and tried to hide.

On the northern flank in the low ground by the river, the Brunswickers and mixed troops who remained under the command of Baum had now engaged the successful Americans. Once the Hessians ran out of ammunition, they drew their swords and proceeded to hack their way free of the swarming Americans. Those Germans who did not break free died on the field. Baum himself was mortally wounded as he fled on foot. He was taken to a nearby house, where he died.

The Battle of Bennington was a complete victory for Stark’s men. Hessian commander Breymann soon made his approach toward Bennington with over 600 men and two six-pounders. A handful of fleeing soldiers from the battle made their way to his divisions and gave conflicting accounts of what had just happened. Sensing the battle was still in full swing, Breymann advanced at once onto the battlefield. American pickets opened fire before scattering, alerting the approaching troops of the hostile environment before them. Breymann established a line of attack north of the Walloomsac River.

Stark’s men were disorganized and exhausted from over two hours of continuous fighting. Bringing order to the militia was surprisingly easier than one would think, but what gains they had just made were now in jeopardy of being lost. At this very moment, by a stroke of good fortune, 300 of Col. Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys arrived from Manchester. Joining with Stark’s now reformed divisions, they hammered the approaching Hessian lines. Breymann’s attempts to thwart a rout were dashed. Both armies of men were exhausted from marching and fighting in the humid weather. But the Americans had enough strength left for a bayonet charge into the German line, which broke what remained of the reinforcements to Baum’s expedition.

Unlike Baum, Breymann managed to escape with his life. In all, over 200 soldiers had been killed by Stark’s men, with another 700 taken prisoner. In the days that followed, Burgoyne had to accept that the mission to raid the rebel supply depot was a fool’s errand. He had wasted nearly 1,000 of his troops in the failed attempt to take Bennington. To make matters worse, of the 400 or so Native American fighters that accompanied Burgoyne’s army at the start of his campaign, only a few dozen remained after Bennington. It seems they lost their appetite for participating in the British campaign. This, coupled with the failure to get the supplies he needed for the army, forced Burgoyne to take a defensive position and wait for help to come from the British army in New York.

The other concern for Burgoyne was the Northern command of the Continental army. While Washington was commander in chief of the entire army, and personally led the main forces in Pennsylvania, the northern army was commanded by Gen. Philip Schuyler in Albany. Soon, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates would be the new commanding officer with the sole objective of destroying Burgoyne. The eventual clash of the two armies in October near Saratoga, New York changed the course of the war forever. But we must not overlook the importance of what occurred at Bennington on August 16, 1777. The Americans led by John Stark had annihilated a sizable portion of Burgoyne’s forces. This led to him having no choice but to call off any attack on Albany. Isolated and surrounded, Burgoyne’s fate was set in motion with the failed attempt to raid Bennington.

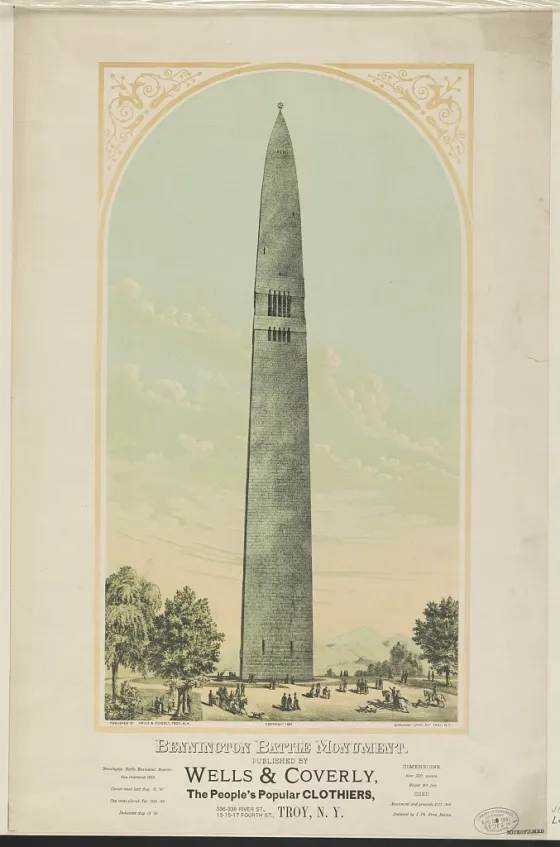

Today, John Stark is considered a hero in Vermont and New Hampshire. A residential neighborhood weaves through the former battlefield while a country club backs up to the Walloomsac River, giving the country a far different appearance than it had in August 1777. The area remains rich in history, and ready for wider recognition as being a pivotal battle in American history.

Further Reading:

- Richard M. Ketchum, Saratoga: Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War, (New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1997). Chapter 15: The Dismal Place of Bennington, pp. 285-305. Chapter 16: A Continual Clap of Thunder, pp. 306-328.

- Max M. Mintz, The Generals of Saratoga, (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990). Chapter 15: Defiance, pp. 167-177.

- W.J. Wood, Battles of the Revolutionary War, 1775-1783, (Chapel Hill, North Carolina, De Capo Press, 1990). Chapter Six: Saratoga: Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, pp. 132-150.

- https://www.britishbattles.com/war-of-the-revolution-1775-to-1783/battle-of-bennington/

Related Battles

70

907