While you may have heard that the Christmas tree tradition is rooted in Germany, you might not associate the German-born American cartoonist Thomas Nast with the jolly holiday! However, if it wasn’t for the creative force of Nast, the modern-day look of the revered chimney-hopping, sleigh-riding, gift-giving, reindeer-wrangling man of the season would look quite a bit different.

An Artist-in-the-Making Comes to the U.S.

Thomas Nast, at roughly six-years-old, came to the United States with his mother and sister in 1846, and settled in New York City. Little did he know that his imagination would become the basis for well-known American symbols. But one thing he was well aware of was the cherished tradition of Christmas in his German household. German immigrants were responsible for bringing a wealth of new holiday traditions to America, essentially transforming the country’s Christmas celebration into one of relaxation, family values, and story-filled practices. The traditions Nast knew as a German immigrant would eventually collide with the art he came to master.

After studying at the National Academy of Design, the then-teenage artist went on to work at Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1855. By the late 1850s, Nast was freelancing for Harper’s Weekly and the New York Illustrated News. In 1860, adventure was afoot for the 20-something, as he went to England for the New York Illustrated News, and Italy for The Illustrated London News and American-based publications.

It was through Harper’s Weekly that Nast’s work would make a splash, as the “Father of the American Cartoon” began covering the clash between the Federals and Confederates in 1862. A staunch supporter of the Union with an abolitionist mindset, his drawings often reflected his beliefs. Eyes darted to his satirized depictions of the era’s political issues and his striking scenes of the war’s battlefields and camp sites, including the eyes of President Abraham Lincoln, who referred to Nast as “our best recruiting sergeant.” Providing the American public with a visual of the tragedy unravelling on landscapes across the country awakened a great sense of patriotism.

A Very Civil War Christmas

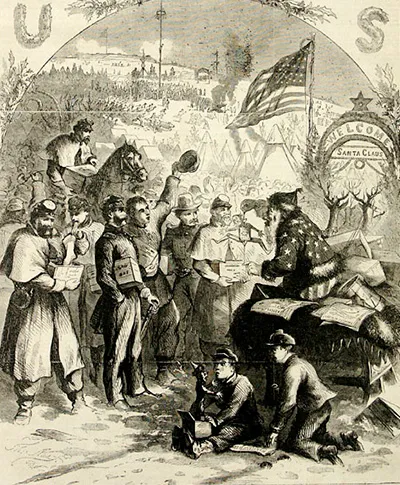

Nast’s Christmas connection to the Civil War was unveiled in Harper’s Weekly on January 3, 1863, introducing Santa Claus as a Union supporter sitting in a sleigh-full of presents, ready to be distributed to soldiers in a Union Army camp. His allegiance is unquestionable, as he donned a star-covered coat and striped pants.

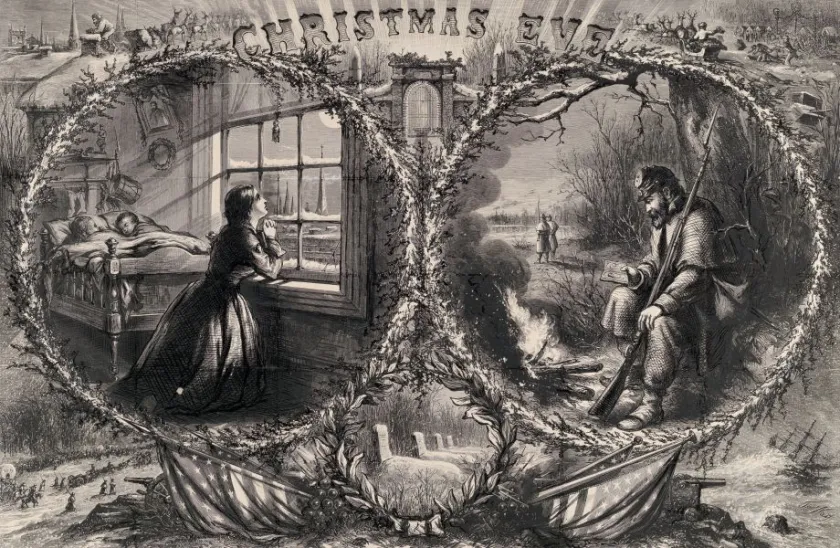

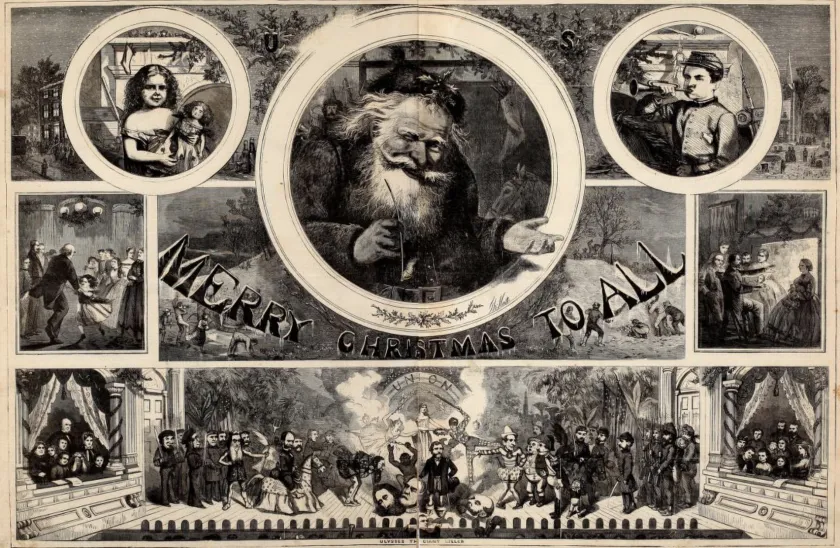

In a separate illustration within the same issue, Nast delivers scenes of Santa flying in his sleigh and delivering presents by way of chimney, likely drawing from the influence of Clement Clarke Moore’s poem A Visit from St. Nicholas. But not only that, he depicts — in two different circles — a woman praying by a snowy window with her children fast asleep in a bed nearby, and a lonely Union soldier perched next to a tree.

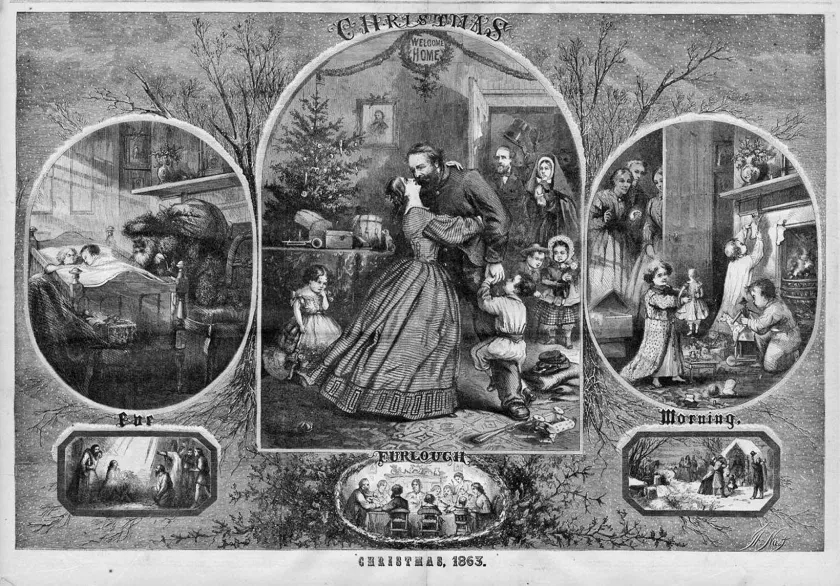

It was in the December 26, 1863, issue, that the same couple is seen reunited, with the Union soldier home on furlough. Meanwhile, the sleeping children are wholly unaware of Santa Claus and his visit, as the bearded figure appears next to a fireplace with a sack of gifts upon his back.

And while Nast gave Santa a year off in 1864, instead opting to depict “The Union Christmas Dinner,” the cheery man returned in the December 30, 1865, issue of Harper’s Weekly. There, those who supported the Union appear to be having a wondrous holiday and Santa — with holly adorning his hat — smokes a pipe and wishes readers a “Merry Christmas to all.”

The New York-raised Nast undoubtedly linked the heartfelt emotions and jolly symbols of Christmas with the Union cause, and, in doing so, created even more powerful pieces of wartime marketing.

Santa Flies Beyond the War

Christmas at Harper’s Weekly was synonymous with Nast’s merry illustrations, which were also chockfull of symbolism that reflected issues impacting American society. From 1863 to 1886, Nast contributed 33 Christmas-themed images. Of which, only one is devoid of a reference to or visual appearance of everyone’s favorite, Santa Claus.

In 1866, Santa is seen preparing for his busy night of gift-giving, in his workshop making rocking horses, sewing “dollies’” clothes, peering through a telescope looking for good children, and checking his “account book” to review children’s behavior. Nast leaves no question whether or not Santa has a packed schedule.

But the most famous of these drawings came about on January 1, 1881, when “Merry Old Santa Claus” took up a full page of Harper’s Weekly. The full spotlight shone on Nast’s Americanized version of the German figure of Saint Nicholas, a fourth century bishop revered for his kind and generous acts — and a figure that the German-born artist had known of since childhood! But upon further investigation, you can also see that this Nast version reflects the artist’s pro-military sentiments, with Santa wearing a soldier’s backpack, and donning a dress sword and U.S. belt buckle. It was during the illustration’s creation that the U.S. government was debating the wages of sailors and soldiers, and Santa’s pocket watch even served as a reminder that the U.S. Senate was left with very little time to make its decision.

Moreover, while Santa generally exuded happiness and goodwill, he was also a means to enforce children’s good behavior with the promise of presents. Prior to the Civil War, the holiday was only recognized in 18 states, but after Nast released the visual of Santa Claus to the American public and the country yearned for peaceful traditions after a divisive, years-long conflict, the nation’s domestic celebration of Christmas was kindled. Industrialization had also increased at a rapid pace following the war, paving the way for the commercialization of the Christmas holiday and an increased push for consumers to purchase presents.

The Legacy Lives On

And as for Santa’s red suit? Thomas Nast isn't connected to the bright shade, as his Harper’s Weekly illustrations were printed in black and white. But if you look closely at his drawings, you can see that Santa is often wearing fur, which is another likely allusion to Moore’s A Visit from St. Nicholas poem. It is often Louis Prang (A.K.A. the “Father of the American Christmas Card”) — a U.S. immigrant of French and German descent — who is credited with popularizing Santa’s festive red suit through a series of postcards printed in the 1870s.

Borrowing from the ideas and traditions employed in Nast’s Christmas illustrations and other mainstream depictions of Santa that followed, illustrator Haddon Sundblom landed upon a version of the holiday’s jolliest fellow that has stuck for decades. Created for Coca Cola in the 1930s, Sundblom’s Santa was a plump man in a red and white suit — oftentimes, with a hat to match!

And when World War I and World War II came about, Santa’s patriotism never faltered.

Despite the changes that have come with the years, America’s idea of this beloved Christmas icon wouldn’t be the same without Thomas Nast having sketched the foundation for today’s Santa Claus.