Debates and oppositions hallmark American politics, and political dissenters have found ways to express their differing views. During the War of 1812, the Federalist Party led New England states’ opposition to the conflict which culminated with a convention in Hartford, Connecticut during the winter of 1814-1815.

Frustrations stemmed from prior to the war. President Thomas Jefferson tried to counter British and French trade limitations due to the Napoleonic Wars and the British impressment of American sailors by implementing embargoes. The Embargo Act of 1807 essentially banned all American exports by sea, pushing the American economy into a depression. Smuggling increased and merchants found loopholes to try to continue maritime trade. The Enforcement Act of 1809 attempted to catch smugglers, but the Embargo Act was repealed later that same year. A new measure—the Non-Intercourse Act—replaced the Embargo Act, allowing American trade with all nations except Britian and France. By 1810, the Non-Intercourse Act was repealed and replaced with some specific restrictions on the importation of European trade items.

The non-importation measures crippled the American economy, which did not recover until the end of the War of 1812 in 1815. Maritime trade fueled much of the wealth and businesses in the New England region, and Federalist Party supporters in these states loudly protested the economic measures. In 1812, following years of ineffective embargoes, President James Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war against Britain.

Many New Englanders and the Federalist Party opposed the war, just as they had opposed the embargoes. Twenty-six Federalists from Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, and New Hampshire met in Hartford, Connecticut during December 1814 to discuss their concerns. The convention met in secret and did not keep records of their discussions. Balance of political power was the root of the concerns and debates: embargoes, War of 1812, military draft, growing power of the Democratic-Republican Party, and concerns about shifting political power to the expanding southern and western sections of the county.

New England governors had disapproved of the War of 1812. The governor of Massachusetts had gone so far as to secretly offer part of Maine Territory to Britain in negotiation for ending the conflict. An idea that liberty was more important than the states’ union rippled through the region in response to the perceived overreach of Jefferson and Madison and the Federal government. Some men proposed secession of the New England states, but this idea was eventually considered too radical and set aside during the Hartford Convention.

Instead, the convention focused on addressing their grievances and modeled their writing after similar documents that Virginia and Kentucky leaders had previously prepared to outline their disagreements with political decisions and party politics. Words and ideas from George Washington’s Farewell Address also influenced the Hartford Convention to pursue national harmony. The Convention prepared a declaration of grievances and a list of proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution and sent these documents to Congress.

The proposed amendments included:

- Limiting any trade embargo to last 60 days or less.

- Requiring a 2/3 Congressional majority for limiting foreign commerce, admissions of new states, or declarations of war.

- Abolishing the 3/5 representation of enslaved people in slave states.

- Limiting presidential power by limiting to one term and not allowing presidents from the same state to serve consecutive terms

The proposed amendments attempted to limit the growing power of the southern and western states, allowing the New England states to retain competitive power in national elections and government. They aimed to create the need for a supermajority for Congress to pass bill, hoping this would prevent a future situation like the embargoes or war declaration that particularly hurt one section of the country. Also, the Federalist Party’s power was declining, and they hoped to limit the Democratic-Republican Party’s power by curbing the multiple presidents from Virginia—like Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe.

The list of grievances and proposed amendments that came from the Hartford Convention had little chance of success in Congress and changes to the Constitution. However, the moderates of the convention had pushed back the idea of state separations or secession and followed the more precedented option of explaining their views and suggesting political changes. The secretive nature of the Convention and the news of Andrew Jackson’s victory at the Battle of New Orleans worked against Congress’s reception of the documents. The proposals did not move into discussion or serious consideration for Constitutional amendments.

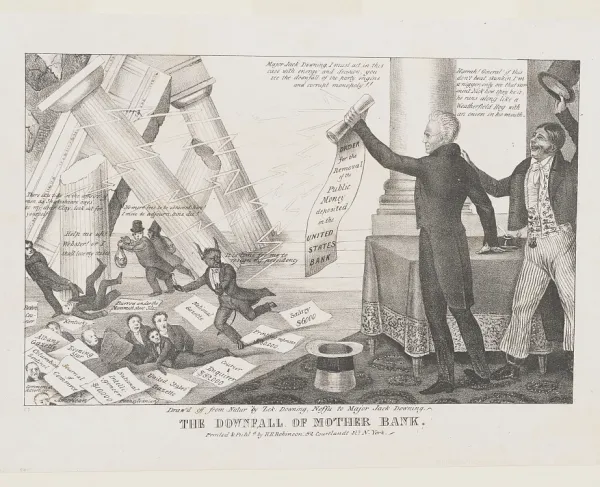

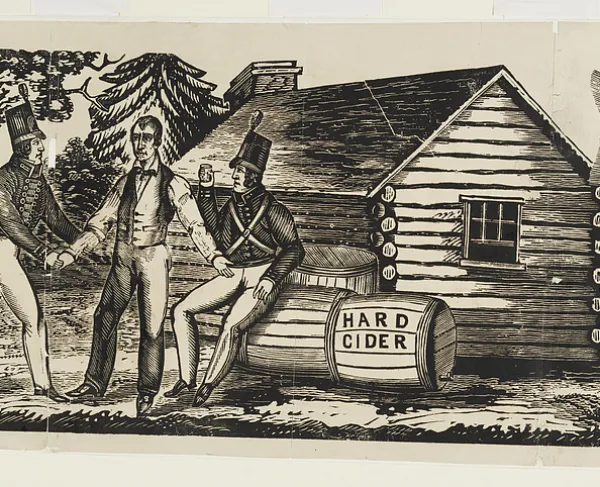

The American victory at New Orleans and the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812, deflated some of the immediate grievances of the Hartford Convention. Political opponents took the opportunity to spin the Convention as a treacherous movement from the Federalist Party. Already in decline, the Federalist Party lost power by the 1816 presidential election, and Democratic-Republican candidate James Monroe won the executive office and ushered in a brief “Era of Good Feelings” and a few years of national unity.