During the American Revolution, about 231,000 men served in the Continental Army and almost 145,000 men served in the militia. With eight years of war and 165 major engagements, most of a soldier’s time in the army was not spent fighting battles, but rather, in camp. For many soldiers, camp life was repetitive and dull. Much of soldiers’ uniformed service was spent doing monotonous work such as chores around camp, drilling, and patrolling. Though not as deadly as a battle, camp life was still dangerous due to poor sanitation, disease, and lack of proper food.

In 1775, when enlisting in the Continental Army, soldiers were supposed to be issued certain supplies to meet their basic needs including clothing, a canteen for water, a blanket for warmth, a knapsack to carry supplies, as well as arms and ammunition. Yet the new central government was challenged at times during the war to meet this basic equipment needs for the army. Continuously supplying quality uniforms and equipment to the army was difficult. Providing literally tons of food to the army every day sometimes seemed near impossible. In November 1775, Congress determined that the following is the Ration of Provisions allowed by the Continental Congress unto each Soldier:

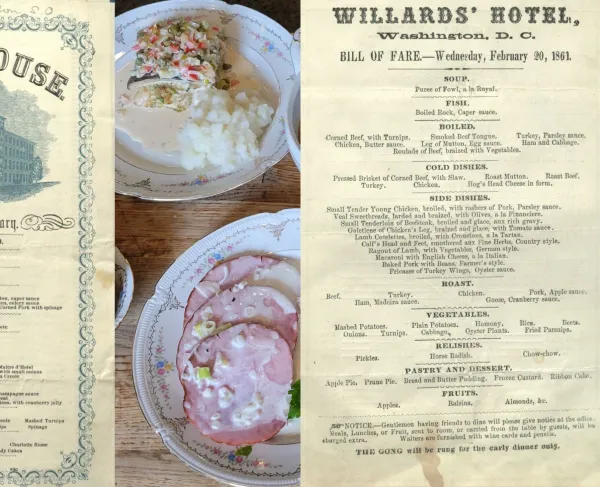

One pound of fresh beef, or ¾ of a pound of Pork, or one pound of Salt Fish, pr diem. One pound of Bread, or Flour pr diem. Three pints of Peas, or Beans pr Week, or Vegetables equivalent; at 5/s. pr Bushel for Peas or Beans. One pint of milk pr Man, pr diem, when to be had. One half pint of Rice, or one pint of Indian meal pr Man, pr Week. One quart of Spruce Beer per man, pr diem, or 9 Gallons of molasses pr Company of 100 Men. One Ration of Salt, one ditto fresh [meat], and two ditto Bread, to be delivered Monday morning; Wednesday morning the same. Friday morning the same, and one ditto salt Fish. All weekly allowances delivered Wednesday morning; where the number of regiments are too many to serve the whole the same day, then the Number to be divided equally, and one part served Monday Morning, the other part Tuesday Morning, and so through the week.

These ideal rations were often not available to soldiers because of preservation and transportation issues. To try and have food more readily available to soldiers, George Washington issued an order in September 1776 for soldiers to always carry two days’ rations with them:

The General hopes, after the inconveniencies that have been complained of, and felt, that the commanding Officers of Corps will never, in future, suffer their men to have less than two days provisions, always upon hand, ready for any emergency—If hard Bread cannot be had, Flour must be drawn, and the men must bake it into bread, or use it otherwise in the most agreeable manner they can. They are to consider that all the last war in America, no Soldier (except those in Garrison) were ever furnished with bread ready baked, nor could they get Ovens on their march—The same must be done now.

Army rations were often hard to eat and distasteful. The meat was salted so that it could be better preserved, and flour was often made into hard biscuits that didn’t mold as fast. Soldiers often complained about these rations. One soldier named Joseph Plumb Martin complained that the biscuits were “hard enough to break the teeth of a rat.” Samuel Dewees of the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment remembered in his memoirs that “sometimes we had one biscuit and herring per day, and often neither the one nor the other…a biscuit and a herring each day, the soldiers lived until their mouths broke out with scabs, and their throats became as sore and raw as a piece of uncooked meat.” Not only were these rations not enough and difficult to eat, but they also had hardly any nutrients. To combat this, vinegar or sauerkraut were eventually added as a weekly ration for soldiers to try and prevent scurvy – a disease caused by a lack of Vitamin C – but that was often not enough, forcing soldiers to find other sources of food from foraging and impressing food from local farmers.

The struggles for food progressively worsened throughout the war. The hardest times facing the Continental Army almost always occurred during winter, when thousands of troops were hunkered down because of cold weather and difficult travel. In the winter of 1777, at Valley Forge, when the food supply diminished, General George Washington tried not to pressure local farmers who themselves were trying to survive the winter. Instead of simply taking supplies, Washington sent out procurement parties to seek out farmers and offer to pay for local goods. However, these excursions were not always successful. Due to the high demand of rations for both Continental and British troops, farmers raised their prices on the foodstuffs they had to sell making it difficult for armies to purchase. Additionally, many were unwilling to sell to the Continental Army because they mostly paid in promissory notes which were widely distrusted among the civilian population. Another method Washington used was authorizing markets in the camps. One of these markets was held on February 9, 1778, near “the Stone Chimney Picket” where local farmers could trade or sell their wares to Americans rather than sell to the British in Philadelphia. However, while these markets were well-intentioned many soldiers had little supplies to trade and little extra money to purchase goods.

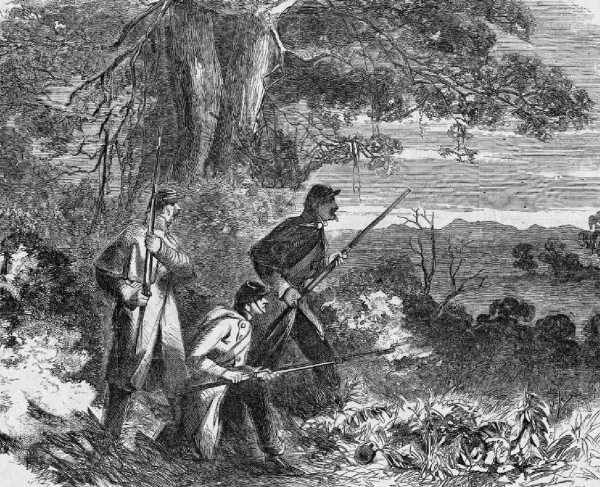

As a result, some soldiers resorted to taking food from civilians to survive. Washington detached troops far from camp to forage for food. Colonel Walter Stewart was sent with a small force to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, while Captain Henry Lee was sent to Delaware, and Brigadier General Anthony Wayne was sent to Salem County, New Jersey. During one of these excursions, Sergeant John Smith recounted when they came across a sheep and two large turkeys, “not Being able to give the Countersign, [they were] tryd by fire & executed buy the whole Division of the free Booters.” Foraging for food did not always mean that soldiers were taking it from local civilians. Some soldiers understood the local vegetation and were able to find food in the woods around camps. At Valley Forge, watercress and sorrel were two common types of greens that were sometimes found and used to provide the soldiers with some vegetables to eat.

The winter of 1779-1780 at Morristown, New Jersey was perhaps the worst winter encampment Washington’s army faced during the entire war. Soldiers sometimes went “5 or Six days together without bread, at other times as many days without meat, and once or twice two or three days without either.” Soldiers were forced to eat what they had available including tree bark, shoe leather, and sometimes even dogs. As a result, soldiers plundered the local area and Washington soon started receiving complaints of cattle, poultry, sheep, and pigs missing. While those who were caught stealing stood trial, Washington was often sympathetic to his men’s situation, and he issued the following General Orders on February 24, 1780:

The frequent occasions the General takes to pardon, where strict justice would compel him to punish, ought to operate on the gratitude of the offenders to the improvement of their morals.

The situation at Morristown improved when General Washington enlisted the help of the local magistrate to request food the army desperately needed and issue IOUs from the Continental Army. If farmers rejected these terms, Washington ordered that “in case of refusal, you [the magistrates] will begin to impress till you make up the quantity required. This you will do with as much tenderness as possible to the Inhabitants, having regard to the stock of each individual, that no family may be deprived of its necessary subsistence. Milch cows are not to be included in the impress.”

Throughout the Revolution, finding adequate food was a constant struggle for the Continental Army’s survival and caused many other struggles that an already overworked General Washington had to confront from disease to poor morale. As he said in his own words, a poor diet of salted meat and flour contributed “to the many putrid diseases incident to the Army and the lamentable Mortality.” Illnesses such as scurvy, dysentery, smallpox, and more ran rampant through the army. With so many of these men dying of starvation and disease, morale became low and desertion rates began to increase, particularly in the winters at Valley Forge and Morristown. Washington was not oblivious to these trends, recognizing at Valley Forge that “this army must inevitably be reduced to one or other of these things. Starve, dissolve, or disperse.”

Despite these struggles, Washington was able to keep the army together and defeat the British gaining independence for the American Colonies. The struggles experienced during the American Revolution from the structures of the Quartermaster Department, to how food was acquired and dispersed would influence the military for years to come.

Further Reading

- The Private Soldier Under Washington, By: Charles Knowles Bolton.

- The Writings of George Washington, By: Lawrence B. Evans.

- Memoir of a Revolutionary Soldier: The Narrative of Joseph Plumb Martin. By: Joseph Plumb Martin.

- Supplying Washington's Army, By: Erna Risch.

- An Edible History of Humanity, By: Tom Standage.